The Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction recently convened a task force for the purpose of expanding dual language programs in our state for all students. Should the initiative get traction and be implemented throughout our state, this would make dual language available across our state. All students would have access to instruction in two languages. As an English language educator and the parent of a child in the Spanish Immersion program in Spokane, the prospect of dual language rolling out for all students is exciting. The benefits of bilingualism are countless, including expanded job opportunities and brain function.

The Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction recently convened a task force for the purpose of expanding dual language programs in our state for all students. Should the initiative get traction and be implemented throughout our state, this would make dual language available across our state. All students would have access to instruction in two languages. As an English language educator and the parent of a child in the Spanish Immersion program in Spokane, the prospect of dual language rolling out for all students is exciting. The benefits of bilingualism are countless, including expanded job opportunities and brain function.

Few districts in our state currently provide dual language programs. However, there are a few ahead of the game and can serve as prime examples of what dual language can look like and accomplish. Pasco school district has a robust bilingual program which particularly supports their Spanish speaking English Language Learners. They are working on expanding to all students. Seattle public schools also has several dual language programs in multiple languages and there are successful programs in Burlington and Mt. Vernon.

One program in particular, though, serves as a model for the potential outcomes of successfully implementing dual language throughout a school – Evergreen Elementary School in the small district of Shelton, Washington. Evergreen elementary school implements a 50/50 model, in which students have instruction in both English and Spanish every school day, across all subjects. This is a key piece to the program. Students have access to academic language for every subject, which is essential to gaining true biliteracy. Additionally, Evergreen serves students from pre-k through 5th grade and has shown tremendous growth in all students.

One program in particular, though, serves as a model for the potential outcomes of successfully implementing dual language throughout a school – Evergreen Elementary School in the small district of Shelton, Washington. Evergreen elementary school implements a 50/50 model, in which students have instruction in both English and Spanish every school day, across all subjects. This is a key piece to the program. Students have access to academic language for every subject, which is essential to gaining true biliteracy. Additionally, Evergreen serves students from pre-k through 5th grade and has shown tremendous growth in all students.

Under the new Every Student Succeeds Act which measures academic growth, Evergreen is a Tier 1 school, outperforming the other two elementary schools in the Shelton school district in academic growth for Hispanics, whites, students of poverty and English Language Learners. In addition, Evergreen has the highest transition rate for English Language Learners. This success is based on data from 2014 to 2017 (See data link below).

An additional impact of the program has been a positive effect on attendance. In Shelton, Evergreen has the highest attendance rate for the whole district at 94.4%. Students are not only learning content and language, but also learn to value school. They enjoy being at Evergreen and are so engaged in their classes and connected with their teachers and one another that they want to go to school every day.

I had the pleasure of meeting the pre-school teacher, Celia Butler. She is from Columbia. Her passion was clear from the moment I walked into her classroom and her connection with her students was inspiring. She greeted her students in English and in Spanish and had a room rich in color and in language. Each tiny student who came in, greeted their teacher with “Good Morning” and a hug. There was love in her classroom – an uplifting community to get them started on there journey through school. This classroom is representative of all the classrooms in this school. This in and of itself shows the community and engagement in a dual language environment.

I had the pleasure of meeting the pre-school teacher, Celia Butler. She is from Columbia. Her passion was clear from the moment I walked into her classroom and her connection with her students was inspiring. She greeted her students in English and in Spanish and had a room rich in color and in language. Each tiny student who came in, greeted their teacher with “Good Morning” and a hug. There was love in her classroom – an uplifting community to get them started on there journey through school. This classroom is representative of all the classrooms in this school. This in and of itself shows the community and engagement in a dual language environment.

I am anxious to see what comes out of the OSPI task force for dual language. With such tremendous programs, like Evergreen elementary, with its excellent student outcomes, the Office of the Superintendent has good examples to draw from in developing the initiative as it rolls out across the state. One of my English language learning colleagues, Amy Ingram, is a member of the Task Force. I’ll be following Amy’s blog, as she documents the work of the task force. Particularly, how it will work in concert with existing English language learning programs and its potential positive impact on recruiting bilingual and diverse educators.

Check out Evergreen Elementary’s date:

(The report is on the OSPI Report Card site. You have to press New WA School Improvement Framework, and then go into the SIF Data Display tab, and click on district and school.)

I am passionate about my students and providing them with every opportunity to advance toward a happy and fulfilling future. For most this means graduating from high school and going on to some sort of post-secondary education. One requirement which can be a hurdle for them is world language. Most universities require students to take 2 years of a foreign language. For my students, English is their foreign language, so studying a language on top of English can be daunting. Over the past two years, though, Washington state has introduced the option to show language proficiency through a

I am passionate about my students and providing them with every opportunity to advance toward a happy and fulfilling future. For most this means graduating from high school and going on to some sort of post-secondary education. One requirement which can be a hurdle for them is world language. Most universities require students to take 2 years of a foreign language. For my students, English is their foreign language, so studying a language on top of English can be daunting. Over the past two years, though, Washington state has introduced the option to show language proficiency through a  Based on my research, it would appear that one major hurdle for Native American students to study and receive credit for their indigenous languages is a lack of qualified and fluent educators to teach the courses and/or to score the exams. Robert Wynecoop and Jamie Valadez are in the minority as highly qualified educators who are also fluent in their respective indigenous languages. However, this is no fault of the individual tribes. For centuries Native Americans have faced the systematic dismantling of their cultures. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries Native American children were sent to boarding schools in an attempt to force them to assimilate to white culture, in an effort to “

Based on my research, it would appear that one major hurdle for Native American students to study and receive credit for their indigenous languages is a lack of qualified and fluent educators to teach the courses and/or to score the exams. Robert Wynecoop and Jamie Valadez are in the minority as highly qualified educators who are also fluent in their respective indigenous languages. However, this is no fault of the individual tribes. For centuries Native Americans have faced the systematic dismantling of their cultures. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries Native American children were sent to boarding schools in an attempt to force them to assimilate to white culture, in an effort to “

With all of my skepticism, there is one particular aspect of the Khan Lab School which I believe would benefit our most underserved students, and with careful planning, could be implemented in our public schools – the

With all of my skepticism, there is one particular aspect of the Khan Lab School which I believe would benefit our most underserved students, and with careful planning, could be implemented in our public schools – the

All persuasive arguments begin with a story. That’s exactly what I was greeted with during my first “Teacher of the Year” school visit to

All persuasive arguments begin with a story. That’s exactly what I was greeted with during my first “Teacher of the Year” school visit to

Beyond the actual buildings, Oakesdale also lacks technology. The district currently contracts with the prison to purchase computers. Inmates refurbish the units, the district buys them at a minimal cost, then they add additional RAM and programs to make them usable. With the passing of their most recent capital levy, along with additional renovations, they plan to purchase Chromebooks for the high school. The computer science teacher is very excited.

Beyond the actual buildings, Oakesdale also lacks technology. The district currently contracts with the prison to purchase computers. Inmates refurbish the units, the district buys them at a minimal cost, then they add additional RAM and programs to make them usable. With the passing of their most recent capital levy, along with additional renovations, they plan to purchase Chromebooks for the high school. The computer science teacher is very excited. While Oakesdale is a great example of the challenges small rural districts face in remodeling and renovating their schools and in acquiring adequate technology (including access to high-speed wifi), it is also a great example of the benefits of a small community. Class sizes are small, and teachers really know ALL of their students. There is even a community calendar that highlights important dates for every member of the community down to anniversaries and birthdays. Individualized instruction is attainable and implemented. It’s also clear that Principal Dingman and the eductors are proud of their school and love to be there. It’s super cool to see.

While Oakesdale is a great example of the challenges small rural districts face in remodeling and renovating their schools and in acquiring adequate technology (including access to high-speed wifi), it is also a great example of the benefits of a small community. Class sizes are small, and teachers really know ALL of their students. There is even a community calendar that highlights important dates for every member of the community down to anniversaries and birthdays. Individualized instruction is attainable and implemented. It’s also clear that Principal Dingman and the eductors are proud of their school and love to be there. It’s super cool to see. Two things you should know prior to reading this post: 1) I am writing through the lens of both a parent and a secondary educator (meaning I’m far from being an expert), and 2) my child has two amazing Kindergarten teachers. They are passionate and kind, they ensure my son loves school, and I can tell they care deeply about him. This is what every parent wants for their children. With these two admissions, I will proceed. I recently received two unsettling emails from my son’s teachers.

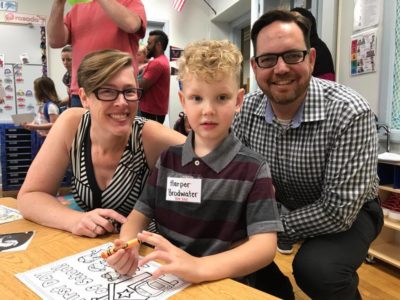

Two things you should know prior to reading this post: 1) I am writing through the lens of both a parent and a secondary educator (meaning I’m far from being an expert), and 2) my child has two amazing Kindergarten teachers. They are passionate and kind, they ensure my son loves school, and I can tell they care deeply about him. This is what every parent wants for their children. With these two admissions, I will proceed. I recently received two unsettling emails from my son’s teachers.

My first year in education, I worked as a Paraeducator in a Designed Instruction classroom. At the time, I didn’t know how deeply that experience would impact my practice as a classroom teacher. I spent one year in that DI classroom. In that time, I instructed students one-to-one on reading and life-skills, and also worked with the whole class to build a boat, to learn independent living through grocery shopping and cooking, and also coached the Special Olympics basketball team. These were amazing experiences and sparked my initial interest in becoming a certified teacher, but the most important impact came from how the lead teacher worked with our team. I didn’t know how much his actions affected me until I took a position in which I worked in concert with others and realized how much I had learned from him.

My first year in education, I worked as a Paraeducator in a Designed Instruction classroom. At the time, I didn’t know how deeply that experience would impact my practice as a classroom teacher. I spent one year in that DI classroom. In that time, I instructed students one-to-one on reading and life-skills, and also worked with the whole class to build a boat, to learn independent living through grocery shopping and cooking, and also coached the Special Olympics basketball team. These were amazing experiences and sparked my initial interest in becoming a certified teacher, but the most important impact came from how the lead teacher worked with our team. I didn’t know how much his actions affected me until I took a position in which I worked in concert with others and realized how much I had learned from him.