By Tom White

By Tom White

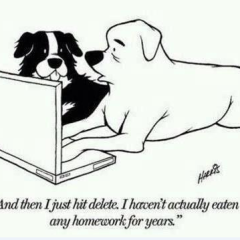

It seems like every few years we go through this. Parents and teachers who hate homework tell us how bad it is. And teachers that don’t hate it keep assigning it. Students, of course, mostly don’t like it and mostly do it anyway. Mostly.

So which is it? A waste of time that keeps kids from enjoying their childhood and keeps families from doing Fun Activities together? Or an essential extension of the school day, providing practice and reinforcement of the skills and knowledge students learned during their time at school.

It’s probably both. Or either, depending on what the homework actually consists of. Continue reading

By Tom White

By Tom White

My son graduated from high school yesterday. I’m very proud of him, of course; he’s a smart, talented kid with enormous potential and a music scholarship to the University of North Texas. He will go far.

My son graduated from high school yesterday. I’m very proud of him, of course; he’s a smart, talented kid with enormous potential and a music scholarship to the University of North Texas. He will go far.

By Tom

By Tom