Last year my district bought a brand-new ELA curriculum for the elementary grades. It has short stories, poems, and even a handful of class sets of novels for teachers to share. There are also nonfiction materials integrated into the standard social studies and science topics of the different grade levels. For example, since fourth graders across America often study Native cultures, the fourth grade ELA curriculum has booklets about Native tribal history and a traditional Native story. In addition, there are booklets about money management, economics, and innovation. For science, the booklets include topics ranging from earthquakes, volcanoes, tsunamis, skeletons, and porpoises. There is also a short biography of an early paleontologist.

Our school day is scheduled around lunch, recesses, specialist time, a set period for math, a set period for reading, plus additional WIN times for math and reading—WIN standing for “What I Need,” whether it’s reteaching, extra support, or enrichment. Last year our fifth grade teachers complained that they had 20 minutes a day to fit in all the district-adopted science and social studies curriculum. “But you are teaching science and social studies in your ELA curriculum, right?” was the response they got.

Well yes. To a degree.

This week I attended a full-day curriculum workshop on the Next Generation Science Standards. The presenter at one point blurted out that he wished that one subject would be dropped from the school day altogether—reading.

Publishers would love to have you believe that they have provided the tools needed for integration by teaching science and social studies lessons within the ELA curriculum. But that’s exactly backwards for how true integration works.

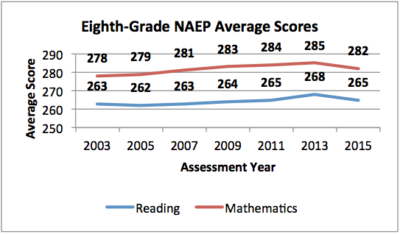

In fact, this backwards system of integration may explain why reading scores have flatlined since 1998!

In fact, this backwards system of integration may explain why reading scores have flatlined since 1998!

According to The Atlantic, “Daniel Willingham, a psychology professor at the University of Virginia … writes about the science behind reading comprehension. Willingham explained that whether or not readers understand a text depends far more on how much background knowledge and vocabulary they have relating to the topic than on how much they’ve practiced comprehension skills.”

The Thomas B. Fordham Institute says improving reading and writing instruction in America’s schools requires teachers taking the lead. “Teachers should tackle the content-knowledge deficit. In particular, they should take the lead in adopting content-rich curricula and organizing their lessons around well-constructed ‘text sets’ that help students build on their prior knowledge and learn new words more quickly.”

For real integration, I maintain that you need to start with your content-rich subject. Start with science. Or start with social studies. Figure out the main topics you will teach over the course of the year and decide how you will organize them. I teach either science or social studies, one at a time, alternating them. I am starting this year with Explorers and then Mixtures and Solutions. Next will be Colonies followed by Space. Finally we will study the Revolution and Constitution, and we will end the year with Living Systems.

Once I have my science and social studies units decided, then I look at my literacy instruction, including reading, writing, listening, and speaking.

I look for fiction and nonfiction books that students can choose, articles I can share, textbook chapters to assign, as well as related short stories, poems, speeches, and plays. Teaching reading in context is the most powerful way to teach reading. By the way, teaching reading in the context of learning about science actually helps improve reading scores (as I learned in a joint Washington State Science Teachers/International Literacy conference years ago.)

I also look for writing tasks I want my students to engage in—articles, short stories, journal entries, poems, research papers. Teaching writing in context is also a powerful way to teach writing. A year ago I was explaining the extensive writing involved in our class’s CBA for social studies. One of my boys put his head down and beat it on his desk saying repeatedly, “I hate writing, I hate writing.” Once he finished his CBA, created his website, and presented it to the class to glowing reviews, his confidence soared and his attitude changed.

I read materials with my class that are well beyond my students’ Lexile level. As The Atlantic also noted, “Recent research indicates that students actually learn more from reading texts that are considered too difficult for them—in other words, those with more than a handful of words and concepts a student doesn’t understand.”

For example, in my advanced 7th English classes we started the year reading Seamus Heaney’s Beowulf, which integrated with our medieval studies. The first day of school I gave a homework assignment; every student was required to watch their favorite superhero movie. (“If your parents won’t believe it, write it in your planner and I will sign it.”) Then as we read the book section by section we compared Beowulf to modern superheroes.

For example, in my advanced 7th English classes we started the year reading Seamus Heaney’s Beowulf, which integrated with our medieval studies. The first day of school I gave a homework assignment; every student was required to watch their favorite superhero movie. (“If your parents won’t believe it, write it in your planner and I will sign it.”) Then as we read the book section by section we compared Beowulf to modern superheroes.

For some of my students, it was their favorite book of the year.

As for speaking, my students stand up and talk in my class every day. They get used to public speaking, debating, and voting with their feet. Integrating speaking is important and can make the day more fun and relevant to our topic. For example, the minute we start our colonial unit, my students also stand, bow, and say “ma’am” every time they answer a question. Why? They are using colonial manners!

If you really rig the day right, the kids will be convinced you are doing science or social studies almost all day long. As far as you are concerned, you might be doing at least two reading lessons, at least two writing assignments, at least two listening skills activities, along with some speaking with a partner and with the whole group, and—oh yeah—you’re also doing social studies or science.

But wait, there’s more. By integrating ELA seamlessly into the content areas, you may find you have more time than you thought.

With that time you can buy back the other activities that make life fun. You might actually have time to do some art, sing some songs, have students do a dramatic readers’ theater or an original skit, teach a dance or rhythmic movement. Or cook something.

Just remember to integrate those projects with your unit’s theme, too.

YES! This is such a powerful, yet subtle shift in thinking from embedding content in ELA versus embedding ELA skills into content learning. Everyday can have science and history! I recently was working with a group studying to become teachers. Half of this group felt as of the Washington State Learning Standards constrict learning in the classroom because it makes for less “meaningful” learning (ie-hands-on). I am going to share this shift you have presented with this group to help them make the leap of appreciating how powerful AND flexible the standards really can be. Thanks!

I think at a certain point, integrating content makes perfect sense. I would assume that in the primary grades, the skills of decoding would be a standalone process…the whole learn-to-read then read-to-learn thing. I also wonder about access for struggling readers to appropriate texts based on where they are as skilled readers…