“Twice-Exceptional” (2E) is a term used to describe a student who is both gifted and disabled. These students may also be referred to as having dual exceptionalities or as being gifted with learning disabilities (GT/LD). This designation also applies to students who are gifted with ADHD or gifted with autism.

Last year, at the end of the school year, I overheard one of my mothers talking to other parents, telling them how hard it had been to get her child admitted into the Highly Capable (HC) program at our district because “no one in the district understands twice exceptional children.”

I didn’t say anything. It wasn’t the time or place. But her child was not the first 2E child I’ve had in my class. He certainly won’t be the last.

Yet I am sure every parent of a 2E child feels the same frustration she felt.

First of all, it can be hard to identify 2E children for any of their needs. They are intellectually advanced enough to devise coping mechanisms to help overcome some of their disabilities. At the same time, those disabilities are like anchors that weigh them down, not letting their intellectual giftedness shine. They can look bright but unmotivated, advanced but lazy. They can look too high to qualify for special ed services but too low to qualify for HC services.

In truth, they may need both.

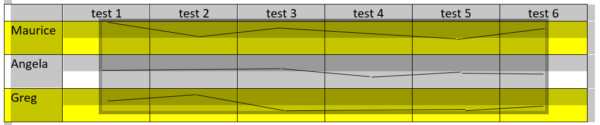

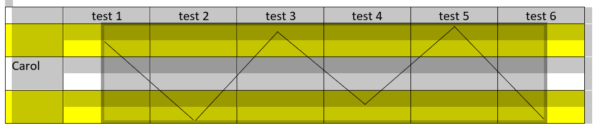

Several years ago I was able to attend an AEGUS conference—The Association for the Education of Gifted Underachieving Students. They had a great tip for identifying the 2E student. Most students, given a test like the WISC-R that breaks out into subcategories, will score up and down along a high band or a middle band or a low band when you graph the scores.

2E students, on the other hand, have results that fluctuate much more wildly up and down. Typically, they will test as really good in some areas and really poor in others.

The conference speakers gave the example of an eighth-grade girl who had published a book of poetry but who couldn’t do the simple arithmetic involved in handling money.

There is an inclination on the part of all of us, I think, to focus on the deficits, to try to shore up the gaps. We are going to get that girl through basic arithmetic if it kills us—and her. We will pull her out of other class time to give her remediation in math. We will torture her with her areas of need.

Maybe what she needs is more time to write.

We have this system of education that requires everyone to meet certain standards for graduation. Take algebra, for example.

I heard Temple Grandin at a conference. She has a PhD. She also has autism. She said if she’d been required to complete algebra to graduate from high school, she never would have finished, much less gone on to graduate work. She explained that she thinks in pictures. Then she showed us a Google image search for geometry. It went on for pages.

Next she showed us an image search for algebra. It was just numbers and formulas.

For someone who thinks in images, algebra is meaningless. It’s gibberish.

And it certainly wasn’t necessary for Grandin’s life’s work on animal behavior.

For 2E kids, it can be far more important to focus on their areas of strength than on their areas of need. I would love to see Washington State exercise more flexibility in graduation requirements. As Grandin says, “Rigid academic and social expectations could wind up stifling a mind that, while it might struggle to conjugate a verb, could one day take us to distant stars.”

For those of us in elementary school, I can pass on another tip from the AEGUS conference. They suggested looking for any place in the school where the student might be successful: PE, music, art, library, math, reading, writing. Where does that student soar?

Then ask yourself, what can you do to duplicate the conditions of that place for the student for the rest of the school day? If she does well in music and nowhere else, can you allow that her to wear headphones and listen to music while she does her other work? If he loves to draw, can you teach the class how to take notes with pictures instead of just with words?

In the end, you may have to remediate some students in reading or math because that’s the way the system works. But make SURE you allow them to accelerate in their areas of strength. They need at least part of each day where they get to fly.

This is interesting, and challenging. What about the twice exceptional student whose areas of need get in the way of the ability to manifest their areas of higher capacity? I’m struggling with my wording here to be respectful… but what if the student identified as 2E is only presenting as once exceptional…if that makes sense? What’s the right way to inquire about the second exceptionality (the area where the student is supposed to excel) if the student isn’t presenting both?

YES! As the parent of a 2E, it is a struggle! It is also a struggle for classroom teachers to be able to identify and support the skills and abilities of these students in the classroom really well. Honestly, I can say from experience that it is asking a lot of a general ed teacher to cover all of the bases of all students all of the time. Thankfully, more and more information is becoming available about these students’ needs and with information, hopefully will come the resources to meet these needs. A parent/teacher of a 2E can dream…right?

Nice article and it’s worthy sharing. Its is really helpful and we need to understand children as each is one of their kind.

Awesome share.!!!!!!!!

Jan,

As always your comments reflect knowledge and empathy. I am so glad you share your wisdom with all of us.

Marcia