On Leveraging Technology—part five: a sorting

When I started writing about technology in the classroom back in October I began with these central questions:

- How do we teach mindful use of technology to students who are already immersed in technology?

- How do I deal with the inherent assumptions in the previous question that imply such immersion is negative?

- Is such immersion negative?

A host of other questions has arisen from my explorations.

Context: My district decided against one-to-one technology adoption after passing our technology levy. The district my children attended adopted one-to-one. The comparison has been interesting. Of course, the comparison is not perfect. I’m a teacher in one district, and a parent in another. Obviously different perspectives. I’ve also made some clear decisions about my kids and technology, and technology in my personal life, which I laid out in the first post.

Here I am at the end of March, the longest month, and where am I really with answering these questions?

It takes a little knowledge to dig a little deeper sometimes. This month, I am hitting the knowledge. Next month – I am digging a little deeper. What am I talking about? Character education! Let’s first get a little history…

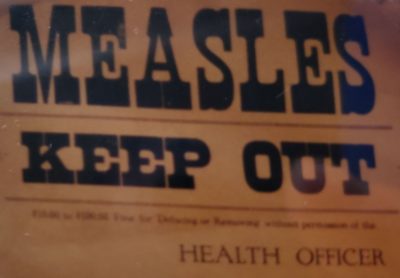

It takes a little knowledge to dig a little deeper sometimes. This month, I am hitting the knowledge. Next month – I am digging a little deeper. What am I talking about? Character education! Let’s first get a little history… The minute my mom was diagnosed, a quarantine poster was slapped on the front door of their house. When her dad came home from work, he wasn’t allowed inside his own home. That’s how seriously they took quarantines in 1938.

The minute my mom was diagnosed, a quarantine poster was slapped on the front door of their house. When her dad came home from work, he wasn’t allowed inside his own home. That’s how seriously they took quarantines in 1938.