When I teach about privilege in my classroom, I’m careful to frame it not as an “easier life,” but rather, a life that more closely matches the life of the deciders.

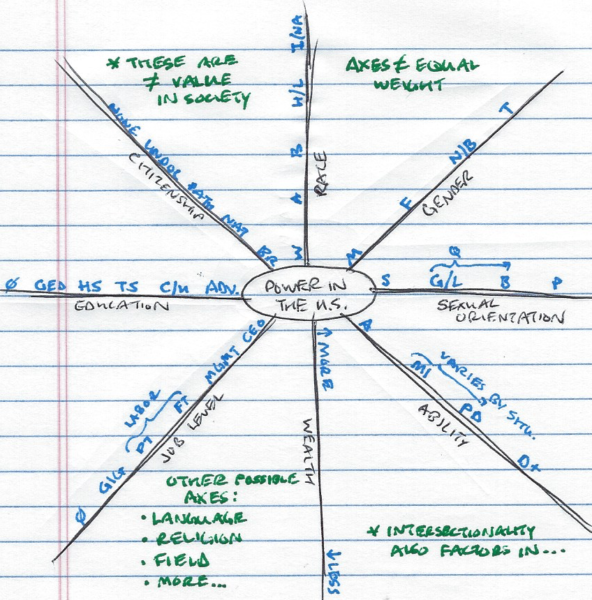

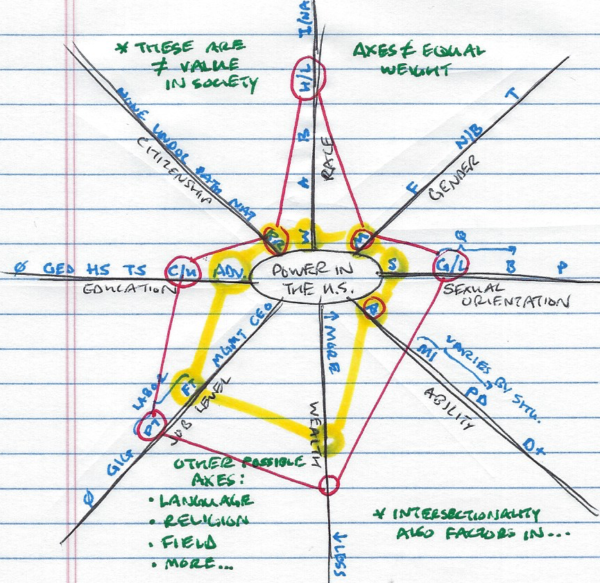

We talk about it in terms of “proximity to power.” As we discuss issues of race, gender, sexual orientation, citizenship, ability, wealth (the list persists), we identify how society unconsciously arranges each of these on an axis. At the convergence of these axes is the “position of power.” Furthest from the convergence are marginalized identities. We talk about this as “social location.”

I am careful to clarify that when we place identities on these axes, we are not making value judgments. Rather, we are making observations based on data. For example, on the race axis we consider which race in our country occupies governmental policymaking seats, CEO positions, media mogul platforms, and socially powerful positions. That race is predominantly white, and disproportionate to that race’s representation in our society. Take gender identity, sexual orientation, sex assigned at birth, (and on down the list) and we get a map of social locations with proximity to power.

Everyday people whose identities are on the axes in most proximity to power have privilege, not because their lives are objectively “easier,” but because our identities match more closely the identities of people who make all the big decisions in society.

The example that drives it home for my kids: What do you have to think about in order to come through the front door of our school? The answers don’t come immediately, there isn’t much thought involved with navigating our front door.

The follow up: If you were in a wheelchair, what do you have to think about?

Yep: Where are the ramps to navigate the curb?

For our building the ramps are off to the side. It means an extra twenty yards or so of travel… not huge, but not something an able-bodied person would need to plan for. That’s privilege. It doesn’t mean you aren’t in pain when you walk, or that your belly isn’t empty or your income is more. It simply means that this one thing you probably don’t ever have to think about is one more small obstacle someone else must deal with to get to the same place you do.

Translating this from such a concrete, visible example to the more emotionally charged and expertly-cloaked-by-society instances of institutional racism is difficult, but not impossible.

Part of why I’ve been working to add new and contemporary voices the literature my students read is because it provides kids the chance to consider worldview different from their own. It becomes easier to accept that racial privilege (and privilege in general) exists when we see stories that show us how others navigate our shared world differently.

As I sat in the meeting a few weeks ago seeking district approval for my use of There There in the senior English curriculum, I benefited from privilege. In this case, my privilege was less about my race and gender (though those I believe always clear my path in ways I don’t perceive) and more about knowing the values and unwritten rules of the system in which I operate. I knew where to find the forms to fill out, and what information to submit. I knew who to contact and how to align my proposal to the initiatives that are the perpetual focus for district administration (because I’ve spent time swimming those waters) and are often second- or third-thoughts for classroom teachers faced with the concrete demands of the now rather than the abstract and sometime albatross of “district vision and mission.”

Don’t get me wrong, I don’t think the approval my proposal to add There There would have been denied had some other teacher than me brought it to the table. I have spent the last few years of my career in literal proximity to power. My privilege meant I didn’t have to think particularly hard about how to get to the table, who to talk to, what to say, or how to navigate the process.

The existence of privilege isn’t a political opinion, it is an observable reality.

I start teaching There There to my twelfth graders soon. My next steps: engaging my students responsibly, avoiding stereotypage, fostering frank discussions about race and historical oppression of indigenous peoples, and bringing in in-person voices other than my own. This last part is my next goal, and I have to admit some major fear of screwing things up: I don’t want my students to hear only from me but in my attempt to create in-person cross-cultural connections I don’t want to cause offense…or commit the equity-in-public-education-sin of expecting the oppressed to educate the oppressor. I’ve reached out to several local tribes and organizations to try to build relationships and form connections, but I don’t know yet where this will take me.

I do know that I want to help my twelfth graders consider their own privilege and how it operates. The existence of privilege isn’t a political opinion, it is an observable reality. We’ll examine There There as a model work of literature, because Orange’s craft makes that easy. As importantly, we’ll explore how the characters’ social locations impact the way they move through a society that has tried for generations to make them disappear.

Excellent post, Mark! I teach a senior level English class called Cultural Studies, and we do something very similar to, but not as well laid out as your “proximity to power” wheel. I’d love to use your wheel sooner than later as we are finishing up Ava Duvarnay’s “When they see us,” and reading essays from the NYT 1619 Project. There, There, is quite a good read and I am so pleased you have moved it through the halls of power to your classroom. I look forward to reading your blogs about teaching it.

Love this post! Thanks for the wheelchair example! I’ve seen my husband face this all our married life.

This is great, Mark. I can figure out most of the shorthand, but would you be willing to key it for me/us anyway, please?

Of course, and thanks for reading. The obvious disclaimer: these are not value judgments and not set in stone… intersectionality matters and context does as well. Of course, not every single identity is listed, and their omission is another example of marginalization in most cases. I’ve found this activity very useful for students, even though it is imperfect.

From closest proximity to power to most marginalized:

Race – white, asian, black, hispanic/latinx, indigenous/native

Gender – male, female, non-binary, trans

Orientation – straight, gay/lesbian, bi, pan/queer not listed

Ability – able, mental illness, physical disability, cognitive/other disability [varies by situation and complexity]

Wealth (not necessarily income) – more / less

Job Level – CEO, management, full time labor, part time labor, gig/inconsistent work/underemployed, unemployed

Education – Advanced degrees, college/university, trade school, high school, GED, no degree/diploma

Citizenship – birthright, naturalized, on a legal pathway, undocumented, no citizenship/refugee

Thank you, Mark. This is a fascinating on-ramp to that much larger discussion you alluded to, one I’m trying to learn how to have with students and get better at having. Thanks for forging the way.

Mark, I love your graphs. And I love, love, love the wheelchair example.

You might be heartened to know that our school is participating in the 2019 Global Read Aloud. For my grade level the book is The Front Desk. by Kelly Yang. The novel tells the story of an immigrant family dealing with racism and exploitation. My kids are loving it, but it’s opening their eyes, too.