By Guest Contributor and Tumwater High School English Teacher, Emma-Kate Schaake

Humble Beginnings

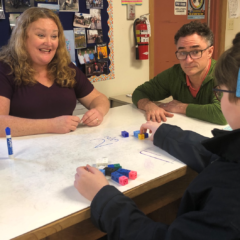

Three years ago, our equity team was the new kid in school and we had all the hallmarks of not quite fitting in.

We dressed a little differently; Black Lives Matter shirts and rainbow pins. We asked questions while our peers rolled their eyes, understandably exhausted on a Friday afternoon. We visibly perked at the mention of data as everyone else sighed.

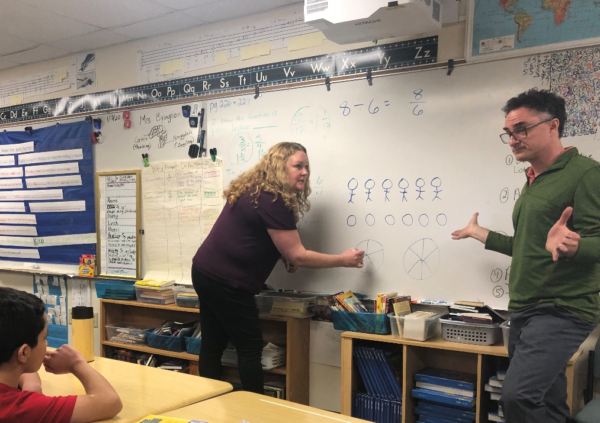

Together, we read articles, analyzed school data, and challenged our perspectives. We wanted to examine our privilege, change our classroom practices, and dream big for the future of our school.

Year one, we hosted a staff professional development session on white privilege and, let’s just say, it didn’t go well. People reacted defensively and resisted the very definition of white privilege. They then shared that we wasted their time, because our school is mostly white anyway.

We had high hopes for systemic revolution, but progress on the ground was slow. We were asking staff to dig deep and examine what they knew about their lived reality, which was inevitably uncomfortable.

Continue reading