There’s an old saying “money won’t solve problems” but usually that’s said by someone who owns a house, has a car, and isn’t worried about Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Washington State isn’t the worse at funding public education but it’s not part of the top ten in the country.

Needless to say, if the Washington State Legislature was fully funding education, we wouldn’t be in the midst of a lawsuit (see McCleary breakdown).

The recently released Senate Republican’s bill SB 5607 tries to address concerns about funding education by including a brief discussion of levies and an extensive description of weighted per pupil funding. I am not an expert in these matters but I think it’s important for all educators to try to engage with these issues.

A little bit of context:

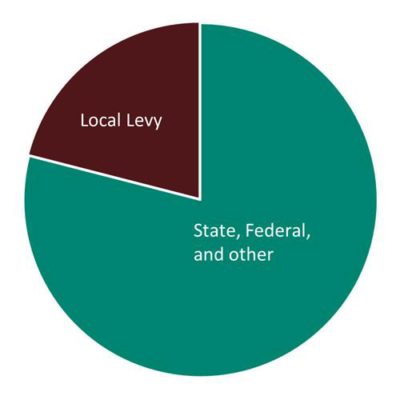

First, in order to think about school funding it’s necessary to realize that levies are a significant factor. As Highline Public Schools explains it, “Levies are for learning. Bonds are for building.”  Thus, levies include everything from staffing (teachers, instructional aids, nurses, librarians, etc.) to supplies like books, computer upgrades, athletics, and arts, depending on what a district has rolled into its levy. It is all this “stuff” that is usually used to calculate what a district pays out in their per pupil costs (have you seen this incredible map?!).

Thus, levies include everything from staffing (teachers, instructional aids, nurses, librarians, etc.) to supplies like books, computer upgrades, athletics, and arts, depending on what a district has rolled into its levy. It is all this “stuff” that is usually used to calculate what a district pays out in their per pupil costs (have you seen this incredible map?!).

Hypothetically, a district’s funding looks something like this pie chart, but every district has a unique set of concerns exacerbated by its location (urban, rural, suburban), its economic stability (employment rates, etc.), and the needs of its students. Thus, some districts rely on roughly 20% of their budget coming from levies while others might rely on as much as 25%.

Second, when we say “per pupil expenditures” we basically mean how much money it “costs” to educate this child. This can include a gamut of things and–from what I understand–might include a portion of a teacher’s salary or costs for programs to mitigate special needs.

I took a dive into Part I: Weighted per Pupil Funding Model of SB 5607 and when I came up for air here are a few of the things that stood out to me. I figure a pros/cons list is one of the easiest ways to address this.

The Pros: A stated focus on equity.

- In the setup of the case for equity is laid out explicitly. “The legislature further finds that the current system unfairly drives more money to wealthier districts, on a per pupil basis, for low-income, special education, and transitional bilingual students than to poor districts.” I appreciate this because while most classroom teachers understand inequity in education funding, it often seems like those who inform education policy do not.

- The term “equity” and “inequities” are weaved throughout the document. This again stands out to me because often in education so much of this system is set around standards of fairness and equality when in fact we need equity. Some school districts or schools within a district need different allocations of funds so that students can be served.

- As someone who teachers AP Language and Composition, word choice matters. I love that the stated objectives of this section of the budget is to provide ampleness, dependability, equity, and transparency.

The Cons: A heap of unanswered but important questions.

- While the objectives are clearly stated, as I read through the budget I continue to ask myself is this budget really ample, dependable, equitable, and transparent? At times the numbers don’t seem to add up.

- Where are the additional dollars for schools coming from? This isn’t clearly outlined.

- How will districts and schools be held accountable for new money, including what are the accountability measures for ensuring money is spent where it is supposed to be?

- Since it seems we are creating a new system, how will district personnel be trained in the new system?

- Since the Senate budget calls for additional funding for special populations of students (ex. ELL, Special Education) can students be counted more than once? For example, will a student be counted as ELL + Poverty + Highly Capable? Is this in-line with the objectives of ample, dependable, equitable, and transparent?

- Are there other special populations (no mention of foster kids anywhere) that are missing or will they be added later–if so, when and by whom?

- What about equity within a school district? If the money goes to the district, but say most of the students with “additional funds” attend one or two schools, how will it be ensured that the money will follow them to that specific school?

There is much to consider in this budget proposal. I encourage you to do your own research, pose more questions for us to ponder, and read this clear, succinct analysis of SB 5607 released by the Equity in Education Coalition last week.

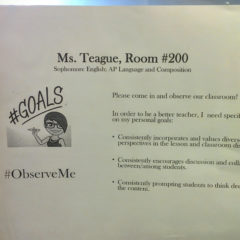

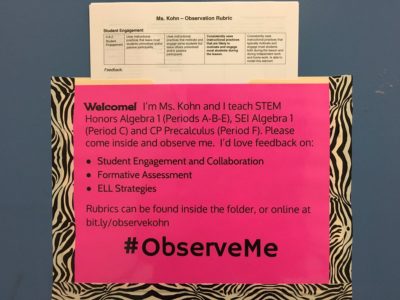

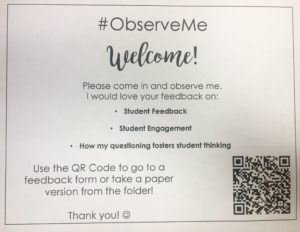

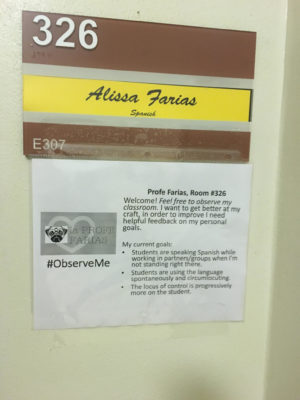

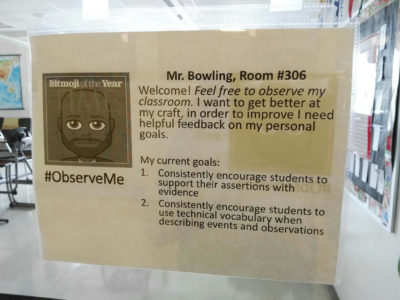

It forces me to have a growth mindset. If this sign is on my door, I am telling the world that I want to grow. I am inviting anyone to come in and comment on my instruct. Yeah, that’s a little scary. But it’s a healthy risk that models vulnerability and openness to others. Who could pop in? A visitor. A parent. The librarian. Another teacher on planning period. I’m both thrilled and terrified at the possibilities. The #ObserveMe challenge reminds us that teaching is relational and we need all types of perspectives to help us grow. This model is based on trust. By opening myself up to the community, I am making them a part of my learning process and saying that I value their voice in my growth.

It forces me to have a growth mindset. If this sign is on my door, I am telling the world that I want to grow. I am inviting anyone to come in and comment on my instruct. Yeah, that’s a little scary. But it’s a healthy risk that models vulnerability and openness to others. Who could pop in? A visitor. A parent. The librarian. Another teacher on planning period. I’m both thrilled and terrified at the possibilities. The #ObserveMe challenge reminds us that teaching is relational and we need all types of perspectives to help us grow. This model is based on trust. By opening myself up to the community, I am making them a part of my learning process and saying that I value their voice in my growth.

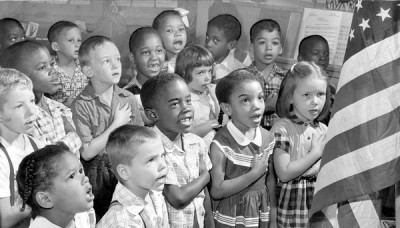

This post is the beginning of a series of posts I will write about 21st century school segregation. I want to start by acknowledging a few factors that influence my perspective and shape my writing.

This post is the beginning of a series of posts I will write about 21st century school segregation. I want to start by acknowledging a few factors that influence my perspective and shape my writing. .

.