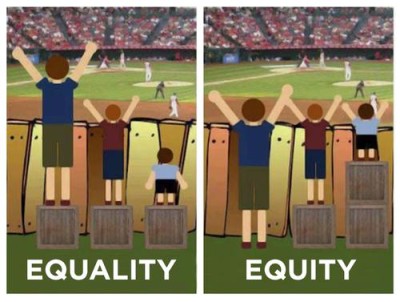

I believe that annual testing can be a tool of equity, revealing critical data that teachers, administrators, and districts can use to improve their instruction for all students, but especially marginalized populations. Moreover, I assert that we cannot separate issues of race and class from our discussion about education policy around standardized tests.

I believe that annual testing can be a tool of equity, revealing critical data that teachers, administrators, and districts can use to improve their instruction for all students, but especially marginalized populations. Moreover, I assert that we cannot separate issues of race and class from our discussion about education policy around standardized tests.

After fifeteen days of SBAC, my post-testing student reflections revealed a delightful surprise. The biggest complaint was not the lack of breakfast, the poor sleep from a loud, crowded apartment, the fact that many read below grade-level, or even the 81° classroom. It was the lack of time to finish the multiple choice section. One student even wrote a hilarious note to the test scorers saying, “if you want me to pass this, give me more time”. So, despite my irritation with lost instructional time, I look forward to the data because I know my students tried their best.

Since Brown v. Board, our country has struggled to provide fair, equitable access to education for all students. In attempts to “even the playing field”, local government created committees like the Equity and Civil Rights Office to ensure that all students have “equal access to public education without discrimination” (OSPI). Their definition of discrimination includes the usual “race, sex, etc.” but nothing is mentioned about inequitable opportunities resulting from teacher biases that only favor students of privilege. Nothing is noted about the dehumanizing effect of low expectations on students of color.

My current concern is regarding the equity of testing data and the privilege it is to “opt-out”. Shortly after my post, a handful of civil rights groups declared opting out was hurting kids The following day a rebuttal appeared arguing these groups are wrong. Reading both articles, one gets a sense that–no surprise–we need more nuance in our discussions about standardized testing. For every “pro” news article, a similar “cons” source will pop up. All stakeholders provide evidence to support their point of view–most of which are insulated by their own beliefs on race and class in America. Few, it seems, acknowledge these limitations. I am certainly no expert on the topic. However, through my research, I am learning the following:

1) Annual testing is a critical component to holding politicians and education accountable to students and their families (see my new fav blogger– Citizen Stewart). Enough said?

2) Despite some effort to enlist people of color in the movement through advocacy and multi-lingual documents, privilege remains a significant and unexplored component of the opt out movement.

I’m certainly not saying that taking a standardized test is a privilege. But the people who opt out have a certain societal privilege. Privilege is what makes opting out a low-stakes exercise in civil disobedience rather than the “academic death” it can be for families and students of color (Stewart).

3) Concealing data gleaned from standardized testing is a civil rights issue.

While all don’t exactly agree, communities of color are writing about the opt out movement as a civil rights issue because standardized tests provide data to measure inequalities (check out recent article and this piece “The Civil Wrongs Movement” ). On the one hand, critics argue that the ranking and sorting of students is detrimental to the learning. On the other, data gives teachers and schools an opportunity–and this is what we’ve termed the “opportunity gap”.

If we remove data we are erasing information (again see Stewart, episode 9).

4) Just because it makes us uncomfortable, doesn’t mean we have the right to erase the data.

I was heartbroken (and angry) when 2/3rds of my 4th period were failing English at semester. I had to accept it and find ways to change the numbers–not by ignoring them but by changing what I did in the classroom. I asked a trusted colleague to map classroom discourse, switched up my routines, and intentionally problem solved. Although it’s not perfect, more kids are passing and excelling this semester. To me, that’s a win.

While I doubt very few opt-out advocates actually want to erase data, their movement has perhaps unintended consequences. Who is the population that is least harmed by this “erasing” of data? Families with economic power and white. We need data to hold ourselves accountable. We can’t have an honest conversation about who we are leaving behind without the data. Using common assessments is a way to reveal gaps for all students, especially traditionally marginalized or underserved. We could spend hours analyzing the ways students are discriminated against on a system wide level, yet once again I will say that discrimination via low expectations for students in poverty or students of color by teachers and other adults remains a primary barrier. Hence, my next point.

5) The way we talk about data reveals our personal biases, privileges and internalized racism.

Notoriously, low test scores get attributed to innate cultural differences and inadequacies, “absent fathers”, and apathetic communities. This is dangerous logic. If I say things like “these kids can’t do that kind of work” or “this just shows they aren’t really Honors kids”, I reveal hidden prejudices in my practice few are willing to call me out on. My experiences with certain educators–many but not all who are white–exposes a need. I heard one opt-outer say in regards to the SBAC that, “We know they [the students of color] will be viewed as failing”. First, “we know” indicates her confidence. Second, “will be viewed as failing” implies this is the only way one can view student scores. I can’t help but think this person has low expectations of students of color. We haven’t seen the data from the SBAC. We don’t know which students will pass or fail. We don’t yet know to what extent the data will be useful. We need to examine how we talk about or represent students of color in our conversations about data. Are we assuming results before they happen? Are we blaming outside factors rather than trying to find the solutions to equipping these students better? Are we masking our own biases, hiding behind a movement?

6) We need more data. More data does not mean more testing. See Nathan Bowling’s post “On Having One’s Cake and Eating it Too”.

To conclude, I don’t have all the answers. I am growing in my process and thinking but I ask you do as well. I want to end on a final thought by Citizen Stewart, “Civil rights groups are right to push for annual testing and to keep the racially unequal results of those tests front and center. They should continue to fight even when friends oppose them. Let’s not be confused: disabling and sabotaging data mechanisms is usually a strategy of people opposed to civil rights, not those who claim to support social progress.”