My mother caught the measles when she was in the second grade. Her overwhelming memory of the ordeal is one of boredom. She had to stay inside the whole time (which could have been up to three weeks). Even worse, in her day, she had to stay in a darkened room, so she couldn’t even read to entertain herself. Of course, there was no television yet.

She didn’t get that sick. She didn’t have any long-term effects.

No big deal.

I have another relative who caught the measles. Robert Dudley Gregory fought with the Union Army during the Civil War. At one point his whole company came down with the measles.

Before I go any further, I want you to consider that the average age of a Union soldier was 26 years old. These were young men in the prime of life who caught a “childhood disease.”

Many of them died. Those who survived were damaged for the rest of their lives.

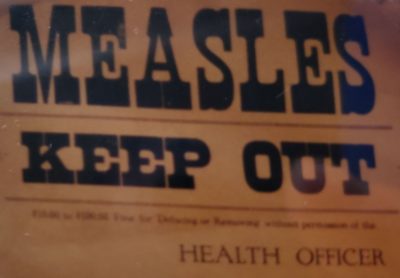

The minute my mom was diagnosed, a quarantine poster was slapped on the front door of their house. When her dad came home from work, he wasn’t allowed inside his own home. That’s how seriously they took quarantines in 1938.

The minute my mom was diagnosed, a quarantine poster was slapped on the front door of their house. When her dad came home from work, he wasn’t allowed inside his own home. That’s how seriously they took quarantines in 1938.

Back in the 1930s people had a more intimate understanding of measles. They knew from experience how contagious it was, how swiftly it spread, and how deadly it could be. They were not prepared to take any chances.

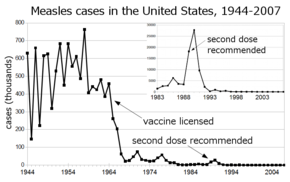

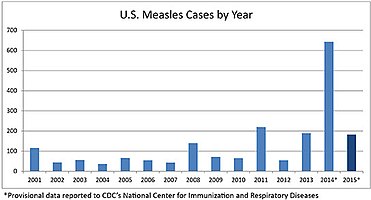

Once the measles vaccine became available in the 1963, it was considered a godsend. Measles went from being as “inevitable as death and taxes” to a 95% immunity rate after the second dose. Cases plummeted. By 2000—in less than 40 years!—it was eradicated in the United States.

Unfortunately, it hasn’t been eradicated in the rest of the world. Measles can be contagious for days before any symptoms appear, so visitors from other countries can bring the disease and spread it here, affecting students, families, classrooms, and school districts.

How is that possible if everyone here is vaccinated? As you’ve seen on the news, not everyone in America is vaccinated. As fewer people vaccinate their children, more catch the disease. So now Washington State is moving toward vaccinating more of its students.

My students sometimes ask about that. They ask, in particular, about measles and autism.

I tell them there was a one individual doctor (see The Panic Virus by Seth Mnookin). He noticed that signs of autism started to appear in some young children after measles shots. After studying a handful of children, he published a paper making the claim that the shots might be causing autism. It raised alarms, as any such allegation should.

Then other doctors around the world tried to replicate his experiments.

(We talk in science about how the ability to replicate experiments is crucial in order to confirm the results of those experiments.)

None of the other doctors or scientists could replicate his experiments. In fact, study after study showed no link between measles and autism.

Then I ask my class, “What should the doctor do, as a good scientist?” They think he should figure out where he made his mistake.

I tell them that’s not what he did. Instead, he went on the internet to tell the whole world that he was right and every other doctor and scientist was wrong.

Now the kids have two lessons they can draw on. They know about replicability in experimentation. They also know that anyone can post anything on the internet. Having a site doesn’t mean the information on it is authoritative. (After all, I teach them how to make sites of their own. They know they are not authoritative! We always ask, “Who sponsors the site? Who vouches for the information posted there?”)

They agree that the American Medical Association and the Center for Disease Control are more authoritative than a single doctor, especially when his studies contradict everyone else’s.

What is interesting to me is how much tension goes out of the room after discussing the issue in those terms. Science. The internet. They feel like they know how those things work. It puts the question in a context they can understand.

Imagine that you are that armed teacher. Maybe you have hours of target shooting. Maybe you hunt. Maybe you are very comfortable with your weapon.

Imagine that you are that armed teacher. Maybe you have hours of target shooting. Maybe you hunt. Maybe you are very comfortable with your weapon.

I have students write in a journal nearly every day. At the beginning of the school year I ask them to write short pieces about gifts or talents they have, ones they wish they had, and ones they are willing to work hard on this year to develop as skills. Often those responses have little or nothing to do with school. They have to do with sports teams or drama classes or art classes. Which is great — I learn a lot about my students’ interests. I have them type those pieces and print them. I hang them on the bulletin board in the hall.

I have students write in a journal nearly every day. At the beginning of the school year I ask them to write short pieces about gifts or talents they have, ones they wish they had, and ones they are willing to work hard on this year to develop as skills. Often those responses have little or nothing to do with school. They have to do with sports teams or drama classes or art classes. Which is great — I learn a lot about my students’ interests. I have them type those pieces and print them. I hang them on the bulletin board in the hall.

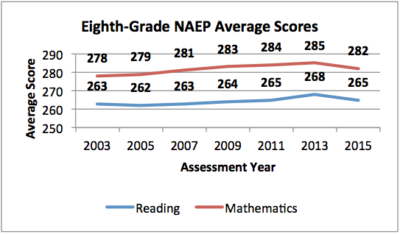

In fact, this backwards system of integration may explain why reading scores have flatlined since 1998!

In fact, this backwards system of integration may explain why reading scores have flatlined since 1998!