I laid awake in bed at the Omni Shoreham. Light seeped through the cracks of the door and laughter drifted up from the courtyard. It wasn’t so much the time zone that kept me awake. I couldn’t turn my brain off. I often can’t turn my brain off.=

I laid awake in bed at the Omni Shoreham. Light seeped through the cracks of the door and laughter drifted up from the courtyard. It wasn’t so much the time zone that kept me awake. I couldn’t turn my brain off. I often can’t turn my brain off.=

This time though, I was thinking about what I’d learned today sitting around the table with teachers, principals, coaches, and district leaders mulling through the Teacher Leader Model Standards and Professional Standards for Educational Leaders. The day’s conversations lingered and added to some of the thinking I’d done with the CSTP Teacher Leadership Skills Framework. I was incredibly grateful to Katherine Bassett (NNSTOY) and those at the Aspen Education Program who thought I should be part of this conversation.

I couldn’t stop thinking: What kind of leader do you want to be? What kind of teacher leader are you trying to be, Hope?

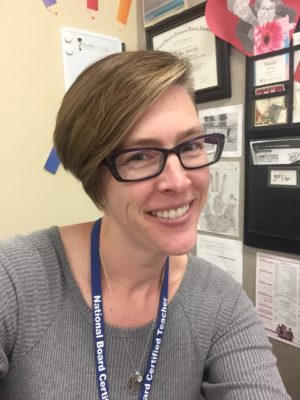

My first “formal” leadership position was team lead my second year of teaching. That same year I was recruited to join a new Equity and Diversity committee. The following year I moved to a new school but quickly found myself leading some curriculum design work. By my 5th year of teaching, I’d served on a district curriculum design team, as a senior team lead, a senior project lead, a Daffodil Princess Coordinator, was offered a job as a litearcy coach (Um, how was I going to tell experienced teachers how to teach?!), and was an NBCT. Fast-foward, add English Department chair, ASB teacher, inquiry group lead, and a few more formal and informal teacher leadership roles in there and you’ll be all caught up to 2017.

I was busy but fulfilled. I learned to work with a variety of personalities. I learned how to navigate a school system. I gained a stronger sense of purpose. Most importantly, I had examples of the kind of leader I want to be…and the kind of leader I despise.

As I contemplate what type of teacher leader I want to be, I am acutely aware of my own hypocrisy. On the one hand, I don’t care about titles at all. On the other, it deeply bothers me when I’m asked so what else do you do besides teach? I find myself stumbling to make up titles for the ways I contribute to the growth of my grade level team, my department, my school and my work with Teachers United.

A title doesn’t make you a good leader. And that’s definitely not the type of leader I want to be. So who do I want to be?

I want to be the type of leader that inspires others to come alongside and follow. The kind of leader who is in expert in instructional and content but doesn’t have to tell everyone about it. The type of leader others know they can come to when they need help creating a lesson plan, a reality check, or a laugh. I want to be the kind of leader who is both well-planned and prepared, but prepared and planned enough to be organic. I want to be the type of leader that doesn’t demand more than they’re willing to give. The leader who checks their emails thoroughly before responding. The leader who thinks about how their choices will marginalize or include others. The leader that knows when to step in and when to step back. The leader who understands that leading is an ongoing learning process. The leader that sees current promise in others and predicts their future greatness. The leader that sees the big pictures and pays attention to the tiny details. The leader who is constantly considering the role race, class, and gender norms play in that moment. I want to inspire. I want to always remain reflective. I want to be the kind of leader who learns from her mistakes. I want to a leader that is humble enough to ask for help, and willing to seek out the wisdom of others. The kind of leader that doesn’t have to talk about how great of a leader they are (I recognize the irony of this blog post).

Don’t get me wrong. I have aspirations of being sharply dressed, breaking out a Tweetable quip, and using big words. I want to remember the name of the author who wrote that one book and recognize Katie Couric when I see her dressed in a blue sweat suit (yes, that happened). But let’s not get carried away here.

Most importantly, I want to be the teacher leader that is a part of a team that shares power, distributes responsibilities and is accountable to one another. They build teams. They are committed to building partnerships with everyone who has something to lose or gain in the work. When I think about my favorite leaders, the ones who modelled and continue to model, this is who they are. They know their why and they never stray from it.