Back in 2008 I was honored to be a regional “Teacher of the Year” for ESD 112. I had the chance to sit in a room with “TOYs” from each ESD, and it was humbling, astonishing, and inspiring to hear all the great work we each were championing in our section of the state.

Then, after the interviews and celebrations and receptions, we sped back to our respective classrooms and put our respective noses back to our respective grindstones.

Lyon Terry, 2015 Washington State Teacher of the Year, likely had a similar experience. The difference was what he chose to do next. He saw highly accomplished educators be selected and celebrated each year, and in that he saw an opportunity: While you might teach down the hall from a TOY and never know it (we teachers are often reticent to share our accolades), titles such as “Teacher of the Year” carry potentially powerful ethos when we enter into policy conversations with non-educators.

Lyon formed WATAC, the Washington Teacher Advisory Council, aimed at pulling together the expertise and ethos of alumni regional teachers of the year. Each year, the number of regional TOYs grows by nine (one for each ESD), so though the group may be small, it is certainly mighty.

This last weekend at Cedarbrook was the 2017 WATAC Spring Conference, where alumni of the TOY program gathered to learn about policy, advocacy, and the importance of teachers telling their stories. It was a powerful and inspiring experience, and I now feel like I am part of an even deeper network of teachers likewise committed to improving public education in Washington.

A big take-away and a good reminder: Everything we do as teachers is somehow impacted by a policy that someone, somewhere has written. Whether it is law from the legislature or rules put forth by a state-level group like the Board of Ed, Standards Board, or innumerable others, people are making decisions that directly impact every move we make as a teacher. Simply put: the people making those decisions ought to be teachers themselves. That’s one mission of WATAC (and CSTP, for that matter), that teachers are not just present at the policy table, but that they are the ones whose hands, hearts, and minds are creating the policy.

For more information about WATAC, here is the website and here is the overview of the program on OSPI’s homepage.

priate for their level in every subject, just like any other special needs group. They require teachers who are trained to meet not only their academic but their unique social and emotional needs. And their number one need must be met on a regular basis—quality time with their intellectual peers.

priate for their level in every subject, just like any other special needs group. They require teachers who are trained to meet not only their academic but their unique social and emotional needs. And their number one need must be met on a regular basis—quality time with their intellectual peers.

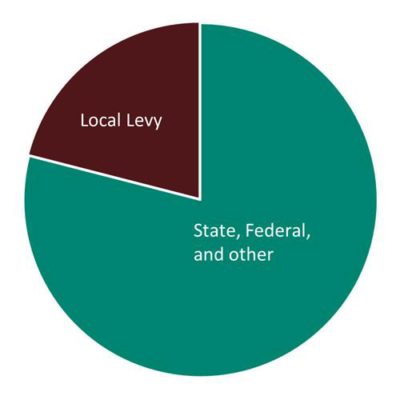

Thus, levies include everything from staffing (teachers, instructional aids, nurses, librarians, etc.) to supplies like books, computer upgrades, athletics, and arts, depending on what a district has rolled into its levy. It is all this “stuff” that is usually used to calculate what a district pays out in their per pupil costs (have you seen this

Thus, levies include everything from staffing (teachers, instructional aids, nurses, librarians, etc.) to supplies like books, computer upgrades, athletics, and arts, depending on what a district has rolled into its levy. It is all this “stuff” that is usually used to calculate what a district pays out in their per pupil costs (have you seen this

I’m getting a new student tomorrow. I haven’t met him yet, but I’ve met his discipline record, and it’s staggering. He’s packed more misbehavior into his short life than most of us commit in a lifetime. Not only that, but academically he’s at least three years below the rest of my class.

I’m getting a new student tomorrow. I haven’t met him yet, but I’ve met his discipline record, and it’s staggering. He’s packed more misbehavior into his short life than most of us commit in a lifetime. Not only that, but academically he’s at least three years below the rest of my class.