I am as frustrated with the legislature as anyone. The Supreme Court has ruled they are not fulfilling their constitutional paramount duty to fully fund public education, there has been plenty of politicking and posturing and planning to plan… but no action.

So I understand Randy Dorn’s lawsuit against seven of the biggest school districts in the state of Washington.

I understand that he’s making a point: Schools across the state are “illegally” passing local levies to fund schools in a way that makes them more functional spaces for educating kids and more appealing workplaces to attract and retain a teaching workforce, and that schools are compelled to do this because the state has failed miserably in allocating adequate funding for public schools.

I understand, but I don’t agree with the move Dorn’s making. It reminds me of the old saying about “cutting off your nose to spite your face.” It’s been woefully clear that threats, sanctions, being legally found in contempt, and even “fines” of $100,000 per day do not influence legislator action. How exactly will suing schools from Spokane to Bellevue to Vancouver (Evergreen) actually influence the legislature to act?

While the Seattle Times Editorial Board came out supporting Dorn’s move (see: “Kudos to Randy Dorn…”) claiming that it will “put pressure” on the legislature, I don’t buy it. Simply put, this puts pressure on those seven school districts to divert resources and energy to a lawsuit whose purpose is obviously aimed at different defendants. This lawsuit exists in a parallel universe to the one in which the legislature operates. I do not believe this will motivate one iota of action. Dorn’s logic, so far as I can tell, is this: As pointed out here by Rep. Chad Magendanz (R-Issaquah), if Dorn’s suit is successful it would mean an immediate loss of two or three billion dollars of levy-sourced school funding before the state legislature has mustered a better funding plan. In theory, this ought to make the legislature sit up and go “Hey, wait a minute! We don’t have a plan yet! Don’t strip away the local funding and decimate our schools!”

But this seems to expose the problem with how the Court and the SPI are attempting to compel action: The threat isn’t really against the legislature itself, the threat is against someone or something else. Those $100,000-a-day fines? Not coming from legislator pockets…and I never really have understood from where and to where that ghost money is to be shuffled. Suing schools? Again, this doesn’t affect the lawmaker him- or herself, it affects the districts subject to the ploy. Still too distant from lawmakers to influence them. Plus, Dorn’s handed them a future scapegoat: If this chess game were played out to the end (which I doubt it would be, thus even further hollowing the whole gesture) and Dorn were to somehow succeed to strip levy monies from schools…leading to RIFs, lower salaries, a mass teacher exodus, cuts in programs for kids…the legislature can all too easily point at Dorn’s suit and say “Look! This mess your children is now in didn’t come from us: It came directly from him.” Of course, it won’t go that far. This suit is a stunt, not an actual endgame to be pursued.

In these stunts and schemes, lawmakers really don’t have anything to be afraid of. So why change course?

Do I, a lowly educator in southwest Washington, have a viable solution that will compel lawmaker action? Where Dorn’s move feels too passive aggressive and face-spiting, maybe my ideas are just plainly too aggressive: Do we lock ’em in a room and not let em’ leave until a budget is built? Do we arrest them for contempt? Do we withhold their salaries until the $100,000 a day is recouped? Since I’m also a believer that fear is a flawed motivator and rarely results in sustainable long term solutions, I’m at a loss for what will convince these people to suck it up, make the tough choices, and do the right thing.

This is where I think Randy Dorn feels he is as well.

Which is why I understand his actions with this lawsuit, even if I disagree and wish there were a different way. The sad part: Maybe there isn’t.

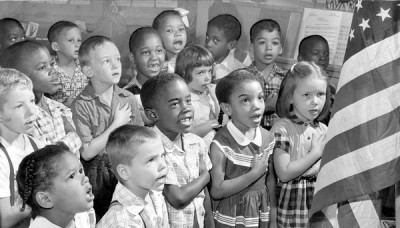

This post is the beginning of a series of posts I will write about 21st century school segregation. I want to start by acknowledging a few factors that influence my perspective and shape my writing.

This post is the beginning of a series of posts I will write about 21st century school segregation. I want to start by acknowledging a few factors that influence my perspective and shape my writing.