By Tom

Over the weekend, the Washington State Democratic Party passed a resolution opposing the Common Core State Standards. This is a pretty big deal, given that the primary opposition to the Common Core has been from Republicans. But while Republican opposition focuses mostly on federal intrusion into state matters, Democratic opposition is mostly a reaction to over-testing and big businesses who profit on that over-testing. Were Washington to drop the Common Core, it would be significant; it’s not only a solid blue state, it’s also the home state of the Gates Foundation, which has backed the new standards since the beginning.

This is a surprising development.

First of all, no matter what you think of the Common Core, you have to hand it to the people behind this resolution. They are an intrepid group. According to their Website, they’ve been working on this project for a year, lining up their ducks and putting the pieces into place. It’s a group of concerned parents, activist teachers and progressive Democrats and it doesn’t look like they’re going anywhere soon. We can probably expect anti-Common Core bills in both the House and the Senate in the very near future.

There’s still a long way to go, of course, before any change in policy. Anything can happen in the legislature. But there’s absolutely no way for anyone who supports the Common Core to see this as anything but bad news. It doesn’t bode well, especially since the Republicans have already come out in opposition to the Common Core and especially since Patty Murray, one of our US Senators, is trying to get the ball rolling on rewriting NCLB. She’s made it clear that she still supports yearly testing, and the only tests we have these days are the ones that are pegged to the Common Core.

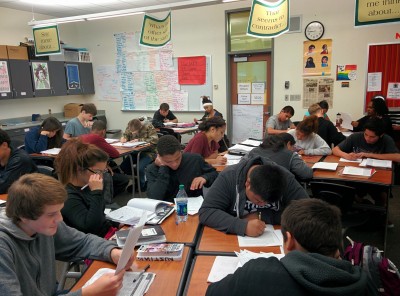

As a teacher, I find this whole mess extremely frustrating. Like most districts, mine rolled out new curriculum in both math and ELA just before the Common Core was written. So, like everyone else, I’ve spent the last five years trying to figure out how to teach to the Common Core with materials that don’t quite fit. It’s been a struggle, but I’m getting there. I’ve also worked hard to get my students prepared for the SBAC, the Common Core-aligned test used in Washington State.

And quite frankly, I like these standards. They make sense. They might not be perfect, but they’re better than the ones we used to have and they’re sure better than what hasn’t been proposed by the people who want to get rid of the Common Core.

We can’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Teachers – and students – have enough to work on without having to abandon everything we’ve done over the last five years and refocus on another set of standards. And while I admire the idealism and determination of the folks who got this resolution passed, I resent their ultimate goal.

We’ve adopted the Common Core. Let’s focus on implementing it.

![By Christine Zenino from Chicago, US [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://storiesfromschool.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/800px-Venice_Fireworks_New_Years_Eve_5334256947-240x240.jpg)