In Aldous Huxley’s early-mid 20th century novel Brave New World, society is medically engineered into five rigid castes. At the top are the Alphas, the genetically and socially gifted; at the other end are the Epsilons, those beings human in form but relegated to work in service to the higher castes.

I used this novel in my Senior Lit and Comp class as one of the works we’d explore while understanding the basics of literary criticism. Brave New World was an excellent study in how to apply a Marxist literary perspective when examining a work of literature. This literary perspective involves looking both within and beyond the world of literature: through the “external” perspective, considering the novel (the physical book itself) as a product within a socio-economic system; through the “internal” perspective, considering the social and economic hierarchies within the story, highlighting the conflict between those who have economic or social power and those who lack it.

We currently seem to live in a world of hyperbole-turned-reality, so I’ll dip my toe in that water: The proposed repeal of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 (HR 610) is a systematic move to cement social castes maintained not by physical engineering as in Brave New World, but rather, by culling and sorting who is bestowed access to education. Where in the novel it benefits the higher castes to keep the lower castes physically controlled, in our world that control becomes control over access to information and education.

The purpose isn’t even hidden. HR 610 isn’t about serving all students: It states from the outset that it is only serving “eligible students,” which is openly defined in the bill as students whose parents elect to homeschool or send their child to a private school.

Further, under the guise of providing this “choice,” this bill undoes protections for disabled students as established in ESEA. It takes steps toward eliminating school lunch programs for low income students. It pretends that it is creating “choices in education.” When we look at who ends up with the power to choose, it is quite clear that this bill has zero interest in providing a free, quality education to all. If it did, the solution would be invest heavily in improving outcomes for all participants in the system, not just for those who want to get away from “those failing schools” through the power to choose one supposed option over another (even though there is growing evidence that non-public schools in the the choice model being proposed don’t actually serve kids better than traditional public schools).

Public education should be focused less on choices privileged adults are offered and more on equipping every young person with full access to ample choices upon becoming an adult. I want every graduate from my school to have the foundation from which he or she can choose virtually any path: university, work, trade school, family…and not feel locked out of any choice because of some action their guardian did or didn’t take when it came time to seek a supposed golden ticket (hollow promise).

Public education should be about empowering those who are born into situations which, for reasons beyond that little child’s control, place that child at a disadvantage in the face of societal systems constructed for the majority race, majority gender, and majority culture. The vision of the American Dream (a Dream never yet realized), with America as a place of opportunity, once included that those in the majority would use their collective power to ensure that those in the minority progress toward freedom from personal and institutional oppression…so that all those American promises remain possibilities.

Whether this bill dies a quick death or not, it is beyond clear that the potential for public education as a societal equalizer is a threat to those in power. HR 610 is not about helping all kids. Period.

After our new Education Secretary, Betsy DeVos, stepped into a public school last week, perhaps for the first time, she told a journalist that the teachers seemed to be “waiting to be told what they have to do.”

After our new Education Secretary, Betsy DeVos, stepped into a public school last week, perhaps for the first time, she told a journalist that the teachers seemed to be “waiting to be told what they have to do.” priate for their level in every subject, just like any other special needs group. They require teachers who are trained to meet not only their academic but their unique social and emotional needs. And their number one need must be met on a regular basis—quality time with their intellectual peers.

priate for their level in every subject, just like any other special needs group. They require teachers who are trained to meet not only their academic but their unique social and emotional needs. And their number one need must be met on a regular basis—quality time with their intellectual peers.

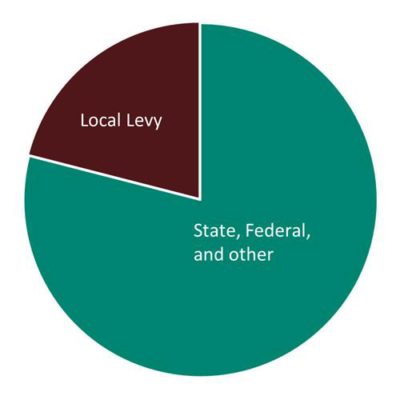

Thus, levies include everything from staffing (teachers, instructional aids, nurses, librarians, etc.) to supplies like books, computer upgrades, athletics, and arts, depending on what a district has rolled into its levy. It is all this “stuff” that is usually used to calculate what a district pays out in their per pupil costs (have you seen this

Thus, levies include everything from staffing (teachers, instructional aids, nurses, librarians, etc.) to supplies like books, computer upgrades, athletics, and arts, depending on what a district has rolled into its levy. It is all this “stuff” that is usually used to calculate what a district pays out in their per pupil costs (have you seen this

I will admit it- I don’t mind our new state teacher evaluation system TPEP. In fact, I jumped on the TPEP bandwagon fairly early. Analyzing my teaching and reflecting upon my effectiveness has been a part of my practice for many years. I certified as a National Board Certified Teacher in 2005 and renewed two years ago. Having facilitated several cohorts of teachers through the process, I can attest to the planning, engagement, and reflection involved in seeking National Board Certification. Those same skills and practices are echoed and assessed in the TPEP process.

I will admit it- I don’t mind our new state teacher evaluation system TPEP. In fact, I jumped on the TPEP bandwagon fairly early. Analyzing my teaching and reflecting upon my effectiveness has been a part of my practice for many years. I certified as a National Board Certified Teacher in 2005 and renewed two years ago. Having facilitated several cohorts of teachers through the process, I can attest to the planning, engagement, and reflection involved in seeking National Board Certification. Those same skills and practices are echoed and assessed in the TPEP process. I’m getting a new student tomorrow. I haven’t met him yet, but I’ve met his discipline record, and it’s staggering. He’s packed more misbehavior into his short life than most of us commit in a lifetime. Not only that, but academically he’s at least three years below the rest of my class.

I’m getting a new student tomorrow. I haven’t met him yet, but I’ve met his discipline record, and it’s staggering. He’s packed more misbehavior into his short life than most of us commit in a lifetime. Not only that, but academically he’s at least three years below the rest of my class.