The headlines are a bit disingenuous. And, I do have to admit I haven’t always been one to jump to Randy Dorn’s defense, but when every news source screams that the Superintendent of Washington schools says it is time to “shut down public education,” there’s a bit of cherry-picking from the message. In fact, Dorn’s actual statement to the Court contained five suggested actions the Court might take, with the closure of public schools being but one. His ideas, not necessarily suggested as concurrent moves, include that the Court might:

- Fine individual legislators for being in contempt.

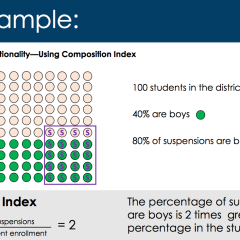

- Order local government to withhold the distribution of local levy monies (since, ostensibly, the patching of financial holes that local levies provide masks the inadequacy of state-provided funding).

- Direct the rolling back of 39 tax exemptions, credits, and preferential rates enacted by the Legislature from 2012 forward, in order to redirect revenue to schools.

- Essentially, shut down non-critical state operations, akin to the “Government Shutdown” move we’ve marched near the brink of in times when budgets haven’t been adopted in legislative session.

- Close public schools (which is the option making all the headlines).

As the shrill cries in the comments sections of articles all over the web point out, closing schools (as well as all the rest) turn taxpayers and children into pawns in a political game. Is it in the best interest of kids that their schools don’t start up this fall? Of course not. Is it in the best interest of kids to simply make plans to make plans, kicking hard decisions further into the future while school walls crumble, the burnout-motivated teacher exodus continues, and inequities in access widen achievement gaps for kids? Of course not. Thus, taxpayers, children, and businesses are forged into pawns in a game that ultimately doesn’t impact the day to day lives of the typical policymaker.

I’m not optimistic that any of Dorn’s suggestions will happen, and I’m not optimistic that the current legislative body in office is really all that serious about finding actual solutions. The main reason is simple: The money has to come from somewhere, either by reclaiming revenue by rescinding current tax breaks or by drawing new revenue in the form of new taxes. Neither is a comfortable proposition. Both require making important, powerful stakeholders unhappy: On one hand it’s the broad voting constituency, on the other is the business community that is essential to our state economy. In either case, a loser must be cast. By converse logic, then, right now both those groups are the relative winners. If the taxpayers and business are the winners in the present model…who is left as the loser?

I think we know the answer to that one.

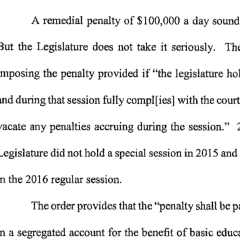

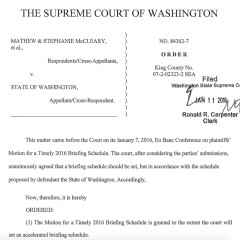

Image source: Cropped from page 5 of the .pdf file of the “Superintendent of Public Instruction’s Amicus Brief Addressing 2016 Legislature’s Compliance with McCleary,” located here.

By Tom White

By Tom White

week I had 42 students in my classroom.

week I had 42 students in my classroom.