Our student-teacher conferences are in October. Of course, I had several student-teacher conferences in September, and I’ve had more in November. I do conferences any time a concern comes up. It may take time to meet with parents and their children more than once in the fall, but it saves time and trouble in the long run.

It may be surprising, but most of my conferences are not focused on academic issues.

I teach students in a self-contained Highly Capable class. For the most part, my students test above grade level in both math and reading. They have above average cognitive abilities. Yet they don’t always achieve academic success, at least not automatically. A lot of them need extra help. Why?

A major pitfall for many of my students is two-pronged: organization and time-management. My most recent conference was with a girl who spends hours preparing for major presentations—her oral book report, for example, or a research report for social studies. When bedtime rolls around she looks up wild-eyed and says, “But I didn’t do my math!” Or “I forgot to study my spelling!” Or both. Her math and spelling scores were suffering as a result.

Her mom and I talked to her about life skills and the need to manage assignments. We told her she needs to do the math homework first (since she likes this least). She needs to spend a few minutes each day on the spelling (instead of trying to learn all the words for the week in one night, and maybe missing the night).

And she needs to break the major assignments into more manageable pieces. We looked at the template for the Power Point for the oral book report, counted the required number of slides with her, and showed her that if she did one slide each night she could do it easily. It was waiting and worrying that turned the assignment into a monster.

Our conference happened to be at the end of the trimester grading period, so I told her I had to apply those lessons of organization and time-management to myself to get all my grading and report cards done!

She left the conference feeling like she could tackle the tasks of school more easily. Her mom left the conference feeling relaxed and comfortable, knowing that she and I were working together to meet the most pressing needs of her child.

I left the conference realizing, once again, that some of the most important things I teach are not on the SBAC. Or any other high-stakes test.

The two best predictors of success are not inherent talent and academic success. They are

- having a good solid work ethic and

- having the ability to get along with other people.

I spend a lot of time teaching my students how to work hard and work efficiently—to challenge themselves, to dig deep, to excel—and at the same time to work smart and do no more labor than they need to do. How to manage their time. How to get themselves and their work organized so they don’t waste time and effort. I explain to them it’s all designed so they have more time for fun.

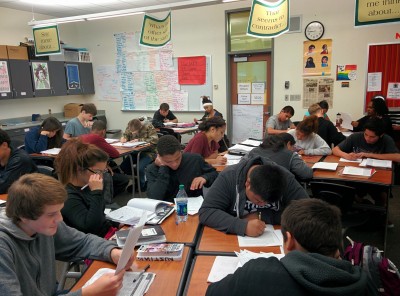

I also spend a lot of time teaching my students how to work together in teams. How to treat each other with respect. How to collaborate. How to be a leader. How to be a follower. How to “share the air.” How to resolve conflicts. Again, I explain that the better they work together, the more fun they will have.

Of course, the better work ethic they have and the better interpersonal skills they have, the better they will do in college and careers. Who knows, these skills may help them in their future family relationships! I talk to them about the long-term impact of the skills too.

Does that mean I want the critically important life skills I teach to be on some state test in the future? Good heavens no! We have more than enough testing going on as it is.

It’s easy to feel overwhelmed with Common Core, SBAC, TPEP, and whatever else is requiring immediate attention. It can feel like an unending avalanche of demands. It’s important to take a breath and get some perspective. Teaching isn’t just about academics and grades and meeting standards and bringing up test scores.

Think of all the things you do as a teacher that aren’t quantifiable.

But some days those things are the most important part of your job.