This year I have more technology in my room than I have ever had in fifteen years of teaching. I don’t know how I feel about it. The phrase in my district is “leverage technology.” I like this quite a lot, especially in contrast to the experience my own children are having in a different district. My children’s district decided to go one-to-one. Technology immersion, seems to be the tactic. It has been a rough transition. As a parent who has used technology mindfully, and been very deliberate about my kid’s exposure to technology, seeing my child use it all the time because he “has to for school” is unnerving. I want to spend some time analyzing these two approaches, and see what I can figure out (if anything). But this post is just background, the setting of the stage.

My early mantra around technology for my personal life and for my classroom was: technology must enhance what I’m doing not distract me from it. I’m not convinced we’ve figured out how to do this in education, as a system. I’m mostly positive a few individuals have figured this out. I’m in the process.

I want to be clear: I am not anti-technology. I coupled my English major with a computer science minor and used contractor jobs building websites to help pay off my student loans. Though I write often in a notebook, all my writing eventually is on a computer. I did resist a cell phone for years, mostly because I didn’t want something else to carry. I teach and have taught hybrid and fully online classes for years. Though, my family hasn’t owned a television in fifteen years.

I am of an age where I can remember the world pre-internet, as I’m sure many readers of this blog are, but I mention it because watching the web come into being taught me something about how I would use it. I lost friends to computers. They just became more interested in the machine and then we spent less and less time together. Nothing too serious, or out of the ordinary coming-of-age stuff, but I noticed. Then, in college, I read Amusing Ourselves to Death by  Neil Postman, and, being the serious minded young person I was, I thought hard about both the messages I received and the medium through which I received them.

Neil Postman, and, being the serious minded young person I was, I thought hard about both the messages I received and the medium through which I received them.

Then I started teaching. I’ve had varying access to technology over the years, and I’ve used much of it. I’ve had a bank of computers, a smartboard, a small cache of laptops (webbooks they were called). But as the technology wore out, I did not feel a pressing need to replace it. It provided a way to do things, not necessarily a better way—as far as I could tell. Besides, a computer lab full of students, oddly silent, staring at monitors creeped me out. I only did it when it made sense—typing final drafts, et. all. Continue reading

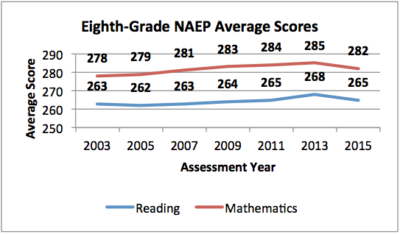

In fact, this backwards system of integration may explain why reading scores have flatlined since 1998!

In fact, this backwards system of integration may explain why reading scores have flatlined since 1998!