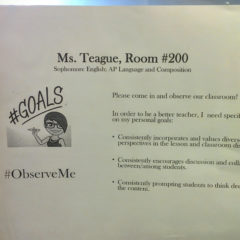

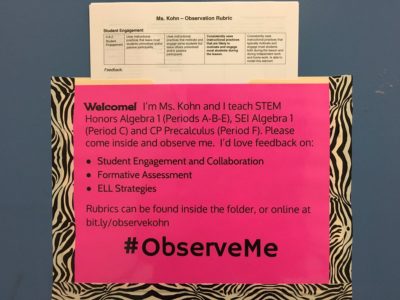

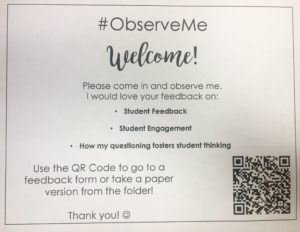

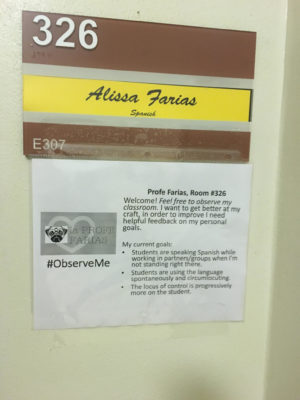

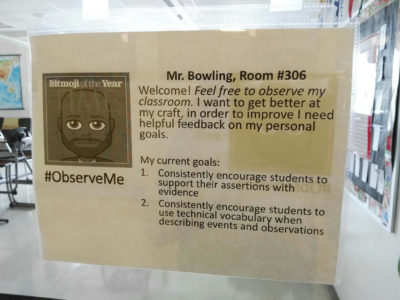

I first spotted the #ObserveMe hashtag on a leisurely scroll through my Twitter feed. This piqued my curiosity. Who’s observing me? What are they observing? As I spiraled down the internet, I found that Math teacher, Robert Kaplinsky, is challenging educators to rethink the way we pursue feedback by making it easy and immediately obtainable. It’s simple. Make a form that says something like “Hi I’m ____. I would like feedback on the following goals:_____”. There is no right way to set up your #ObserveMe sign. Then, adjacent to this invite place a reflection tool. From reflection half-sheets to QR codes connected to google spreadsheets, a teacher can embrace any way that is easy (and I’d argue most meaningful) for them to receive this feedback.

I discovered that while #ObserveMe isn’t quite trending yet, it’s catching fire even at the university level. In teacher prep, some professors are using it as a way to model to preservice teachers the need for a clean feedback loop. Today’s teachers are constantly working to fight the isolation that can happen in this profession. We are also always looking for ways to improve and receiving meaningful feedback on our instructional moves is hard to find. Here’s what I like about Kaplinsky’s challenge to teachers.

It increases the frequency of feedback. With #ObserveMe, I don’t need to wait for my administrator’s scheduled visit. I don’t need to wait for end of unit or end of course student reflections. I don’t need to wait for my instructional coach to find time to come into my classroom. I don’t need to wait for a colleague to get a sub so they can meet with me about student learning. In fact, this has the potential to give me more, real, immediate feedback from a variety of perspectives than anything I’ve seen this far in my eleven years of teaching.

It forces me to have a growth mindset. If this sign is on my door, I am telling the world that I want to grow. I am inviting anyone to come in and comment on my instruct. Yeah, that’s a little scary. But it’s a healthy risk that models vulnerability and openness to others. Who could pop in? A visitor. A parent. The librarian. Another teacher on planning period. I’m both thrilled and terrified at the possibilities. The #ObserveMe challenge reminds us that teaching is relational and we need all types of perspectives to help us grow. This model is based on trust. By opening myself up to the community, I am making them a part of my learning process and saying that I value their voice in my growth.

It forces me to have a growth mindset. If this sign is on my door, I am telling the world that I want to grow. I am inviting anyone to come in and comment on my instruct. Yeah, that’s a little scary. But it’s a healthy risk that models vulnerability and openness to others. Who could pop in? A visitor. A parent. The librarian. Another teacher on planning period. I’m both thrilled and terrified at the possibilities. The #ObserveMe challenge reminds us that teaching is relational and we need all types of perspectives to help us grow. This model is based on trust. By opening myself up to the community, I am making them a part of my learning process and saying that I value their voice in my growth.

It will definitely impact students. If we begin the year with this signage, we are modeling the culture of learning we are trying to cultivate in students. We should be getting feedback that we can implement the next day. I will have concrete date for how I implemented my feedback and can brag about that to my administrator at my evaluation (wink, wink). This has the possibility of transforming my instruction and hopefully inspiring the observer to work on something in their classroom.

So far, a handful of teachers in my school are ready with their signs (they gave me permission to include below). I’m hoping our vulnerability will encourage others in the school to jump on board, foster deeper conversations about goal setting, and improve our practice.

Anyone else up for the challenge?

If you’re on Twitter, post a picture and use the hashtag

#ObserveMe