About the time my middle son (now 8) graduates from high school, my wife and I will still be a few years shy of paying off our student loan debt. We both have Masters Degrees in our respective fields, and finished our undergraduate studies in 2001.

Absolutely, we did this to ourselves. MATs, MSWs, and undergraduate degrees in English Literature and Sociology aren’t fast-track degrees toward high pay and easy loan payoff. We also added other debt and expenses to ourselves by buying a house and having three kids. Choices, and of course we could have made different ones. We live modestly, are natural homebodies, and weigh every expenditure carefully with a more secure future in mind. In reality, we’re doing better than fine.

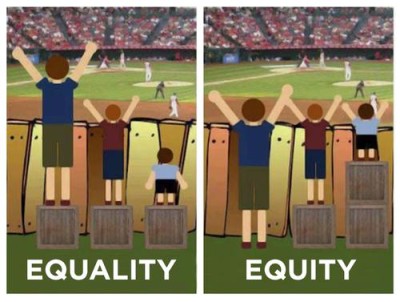

I have a lot to be grateful for, but nonetheless have spent a great deal of the last twenty years pretty frustrated with the way things all turned out. Growing up, I heard again and again how hard work and doing well in school would offer some sort of guarantee (the “American Dream,” of course). I went to a small, poor, rural high school that had exactly zero honors or AP offerings; I grew up on a farm and took four years of Ag instead, not a bad thing at all (I was heavily involved in FFA, and probably learned more about teaching from my FFA experience than I did anywhere else). However, instead of applying any of the practical skills I learned in Ag, I went to University, since that was heralded as The Right Thing To Do. Meanwhile, a few of my friends chose not to go that route, instead getting jobs or learning skilled trades. Now in their late thirties many own their own businesses, employ others, and earn a solid living for their families in fields such as construction, cosmetology, and plumbing just to name a few. Along the way they found avenues for continued learning, whether it was taking some classes on business management or learning on the job from mentors and peers.

They worked hard to make their lives a success, of course, but hopefully you see my point: they chose the exact route that is so quickly dismissed by our system today.

.

.