It’s Tuesday, September 22, 2020. School started on September 2. We are three weeks in.

Due to health concerns, I moved from my fifth-grade classroom at a brick-and-mortar school to teaching at our district’s online academy. I get up and dressed for work each day. Then I walk down the hall to the study or the dining room table or the card table in the family room.

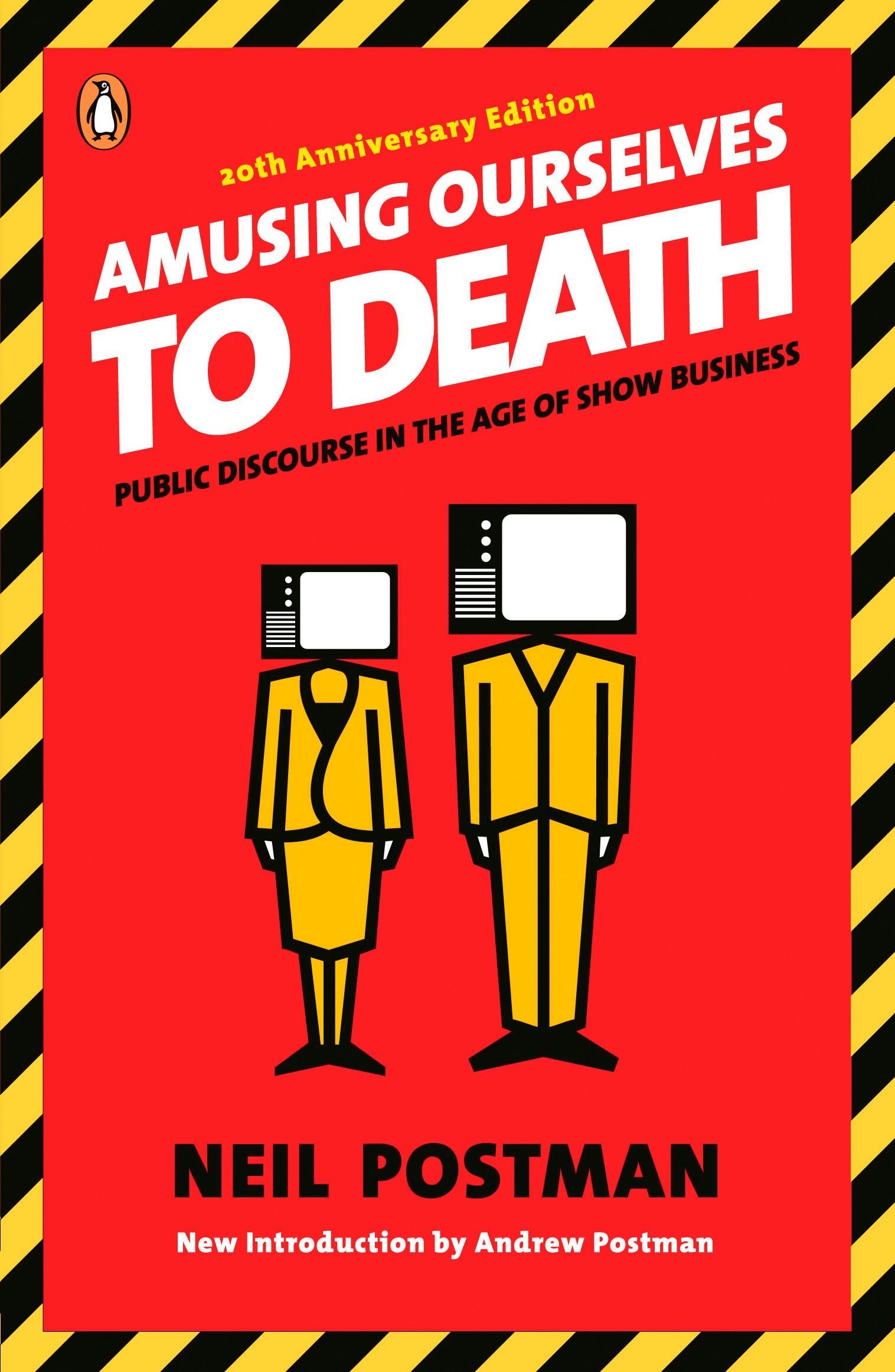

Continue reading Neil Postman, and, being the serious minded young person I was, I thought hard about both the messages I received and the medium through which I received them.

Neil Postman, and, being the serious minded young person I was, I thought hard about both the messages I received and the medium through which I received them.