Next week is our first support group meeting.

By name it is a “New Teacher Workshop,” but I know what it really is. When we gather those dozen newly-minted first-year teachers together, it isn’t going to be a time for “digging into the framework” or “unpacking standards” or “doing a data dive” (whatever that is). Instead, we’ll have an hour or two, with snacks and school-appropriate beverages (this time) where we can just be in a room with the only other people who understand what we’re facing: the October-January “Disillusionment Phase.”

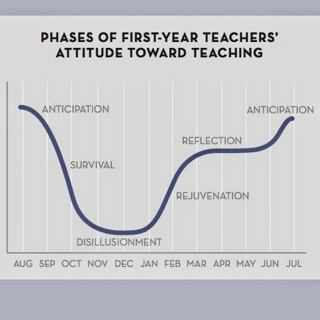

This chart may be familiar to some. It originally came from Ellen Moir in 1999 as part of the Santa Cruz New Teacher project, and described her observations about first-year teachers:

You’ll notice I’ve lumped myself in with that crew, even though I’m solidly “mid-career.” The reality is that I am a novice in my new work of working with novices, and I too am facing that roller-coaster of feelings: we’ve sped swiftly past the “survival” stage and the track is pointing down, down, down.

My charge, however, is to make sure that all those new teachers (and I as well) make it out of that “disillusionment” phase. Too many teachers don’t, and the cards are in more ways than ever stacked against them: the lengthening to-do list of obligations, the perpetually bitter attitude the public holds toward teachers, the ever-changing assessment and evaluation march waving the banner of “accountability.”

One key message that I’ve been repeating over and over with all 50 of our district’s new hires (as well as those first-years who are my primary focus) is that we as individuals have the power to define far more about our experience than we often realize. Yes, our work is hard and complicated, and yes there is testing and standards and pressure and never, ever, ever enough time. Yes, there are colleagues who complain and principals who demand. Over every one of those topics we may feel we have zero control or influence…especially when we are transitioning from the “survival phase” into the “disillusionment phase.”

While we do not control the acronym parade of public education, we do have complete control over our own reactions and attitudes. I’m not saying we ought to blindly roll over and comply with x, y, and z; rather, we ought to take full advantage of the choice to intentionally select that attitude with which we greet each day. That is why we wrapped up our first New Teacher Orientation session last August with the story of Amy the broken unicorn and her husband Bobo the formerly menopausal med student.

In a way, the idea of disillusionment can itself be taken one away or another. It’s surface connotation is one of defeat or negativity. If we break down the word and intentionally interpret it differently, the meaning can shift: the prefix “dis” is from Latin for “away” and typically means a reversal or removal. This dis-illusionment phase is when our abstract illusions about our work are shuffled away…that theoretical image of what we thought teaching might be like has been replaced with a reality. That is all that disillusionment has to mean. What matters now is how we choose to view the reality of our work. The assumption underlying “disillusionment” is that when the illusion is removed, what is revealed is inherently worse.

But that is a choice.

Next week when I meet with those exhausted, over-worked, first-year teachers, my goal will be to help them to shed whatever illusions they may have had about having their own classroom and instead see all the real things about this work that make it such a wonderful job.

I’ve been doing this for over thirty years and my school year still looks like that curve. The highs are lower and the lows are higher, but the general shape is more or less the same.