I work in a diverse, high poverty high school of 1400 students on the Eastside of Tacoma. My students listen to Kendrick Lamar, Miley Cyrus, and Rascal Flatts. They claim daily meals of pho, collard greens, and hot pockets. Many come from chaotic homes where they are often raising themselves and their siblings. Others have parents or guardians who attend conferences, send regular emails and volunteer on picture day. All have the human need to connect. Each one has a desire for relationship—to be known and accepted as they are.

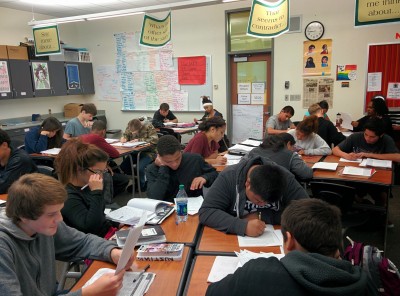

Effective teaching requires meaningful relationships. This is especially true in high poverty communities where the only sure thing is instability. Balancing content standards and relationships is challenging enough without the added layers of systemic racism, economic hardships, and over crowded classrooms. I must learn to navigate, relate to, and design individualized lessons for anywhere between 140-150 students each day.

I’m good at what I do. But the more students I see throughout the day the less individualized instruction becomes.

This year I have two classes of 31 students. With my smaller classes later in the day, I’m not over contract limit. That said, I would give many a precious thing for those classes to be reduced. I only have room for 30 desks so everyday “Mike” (the last kid scheduled in) shows up and grabs a spot by the printer. He waits until someone is absent (which isn’t that often) and then takes their spot. I try to remind him daily that he is welcome in class and a part of our community but physical space sends a different message.

That class is also filled with large personalities, each heart hoping to be accepted and each voice longing to be heard. Which means it’s loud. I teach in a way that riles kids up. When kids start arguing about whether Jing Mei’s mom should’ve slapped her earlier or was forcing unrealistic and harmful expectations on her nine year old in The Joy Luck Club, it’s tough to enforce discussion norms and get students to respect wait time. Every child is looking to be heard.

The need to be heard

We are told that class size doesn’t matter or isn’t a high priority. I can’t help but notice that every elite private school and four year university publishes their sub 20 class sizes on page 2 of their brochure.

Meanwhile, in Washington K-12 we live a different reality. For two days last year, I had 41 students enrolled in my first period English class. That’s FORTY ONE 15 1/2 year olds in a room trying to learn how to read, write, and think. Imagine how this would have influenced student-teacher relationships. Consider the impact on student discourse. In a 55 min period that gives each kid about 1.34 minutes to speak IF a teacher doesn’t use any of the airtime. If a teacher has a 20 minute lesson then that decreases student talk to roughly a minute per child.

Students of all ages desire to be heard. They want to know they exist in the world and others validate their existence. In an academic context, students, although sometimes nervous at first, want to share their ideas with a classroom and want affirmation that their thoughts are accepted and show understanding of the lesson. Furthermore, academic student talk is the primary way students learn and stay engaged with content. Strategies abound from the common “turn and talk” to whole class seminars. Yet, when a classroom is bursting with students, there is little time for student talk.

So when 6’3″ football and basketball players start hollering about what is and isn’t a textual evidence supported theme in Siddhartha, I have little choice but to step back, ride out the discussion. In crowded classrooms, some students will fight to be heard while others will float through a class period without ever sharing a single idea.

The need for meaningful feedback

Students want meaningful feedback. They want to know that their effort on homework was well spent and that they are making strides towards academic goals. Certainly, strategies exist for peer to peer feedback sessions but often it is not taken as seriously as teacher feedback. Why? I believe it’s because I’m the professional. I’m the one trained in my content and can see both potential and possibility in a student’s work. They want to hear from me.

That’s why this weekend (and most Fridays) I pack up my Kia with between 100-130 journals. I use these composition notebooks to inform the next week’s instruction, while giving kids immediate feedback on their learning. The math is stark. I spend between 3-5 minutes reading and commenting on the journals. That task creates roughly 7.5 hours of grading. There are fewer than five hours of scheduled planning time in a teacher’s week. I almost always take work home because meaningful feedback takes time and I know my students need the feedback.

The crowded nature of classrooms across the state is real. I know each teacher is doing their best with the conditions they have. I want to see these conditions improve. Yet, no matter how many kids are in my care, I will still work to develop trusting relationships with each, support academic discourse, and give them meaningful feedback whenever possible.

.

Pingback: Class Size – A Math Problem | Stories From School

To give quality feedback on an actual paper takes me, on average, 15-20 minutes, if I work as fast as I can. Four more students means one more hour of my life donated to grading essays, stories, reports–because I certainly am not paid any extra for the extra time I put in.

No wonder teachers assign fewer writing projects, or offer less written feedback on them.

I can’t agree more! I go to my brothers school, and everything is just the exact way you described it as. But the thing that I’m noticing is that even though he’s in SPED the class sizes are worse than what they were when I was in middle school at Lochburn. The thing that sucks about it is that a normal SPED class size now is normally 25-30, but when I was his age it used to be 15-20 kids. And general population classes were 25-30 and now they are 35-40. “because of budget cuts” yet I think somewhere up the line in the district someone is abusing the money.

Pingback: RT @maren_johnson: RT @SunKPwrz My friend @EspiOnF… | EducatorAl's Tweets

For me, the feedback piece you mention helps to create the other two: feedback is often how I build a relationship with students, they get to know my expectations, and they get validation of their thinking so they might be more willing to speak up. My feedback also lets them know someone is listening (reading).

For ten years, I taught in a program that capped class sizes at about 23 (for 9th grade English). Even the difference between 23 and 28 (let alone over 30) is dramatic, for all the reasons you describe.

Rudi–you are right. We will still invest time to help our students regardless of the class size.

Heather–you bring up a great point that no one seems to be talking about. We are so focused on numbers rather than the diverse needs. I was thinking about that subject while I wrote this piece. A few years ago I taught a sheltered ELL class and only had 12 students, but it felt like 100 because everyone read/wrote at such varied grade levels. I was teaching a district required 10th grade curriculum–most of my students were not even close to that reading/writing level. The workload was extremely stressful as I was constantly trying new ways to unpack the curriculum. I’m so glad you have a supportive superintendent!

Your school sounds interesting. Education policy folks love to talk differentiation and push it on teachers but somehow those same folks forget that an equitable system needs to be a differentiated one. I really wish there was more focus on differentiated funding and support for schools based on their student population needs. Keep doing the good work that you are! Your kids need it!

I teach 15 students every day. Sounds awesome, right?

What if I told you that I teach first, second, third, AND fourth grades…at the same time, in the same classroom. Doesn’t sound as good. How does my one hour of prep each week sound? Not so awesome. Those needs you wrote about aren’t being met in my classroom the way I would like them to be.

Class size is extremely important, but so is grade configuration. For very small schools, like mine, the number of kids matters far less than the number of grades. I would love for there to be a class size limit, but also some kind of way to look at small schools differently. My school is funded for 1.4 teachers (K-8). It doesn’t work, no matter how many kids there are in the classroom.

(Sidenote: I spoke to my amazing principal/superintendent, who is also teaching Kindergarten full time, about my need for more prep. She found a way to make it happen so that I could have the time to get the materials ready to teach. There still isn’t enough time in the day to do what I know is good teaching. I have resigned myself to that and to the fact that I am doing a great job, considering what I have to work with.)

Heather, this is certainly an issue that I have never thought about. I wonder if there ought to be a different funding structure for schools under a certain size?

Thank you for describing what is an all too familiar situation of overcrowding. Having once taught in a private school with classes having fewer than 20 students, I wish the experience for all teachers. Of course, class size matters — and so does total student load. By the way, I didn’t work any fewer hours evenings and weekends than you describe, but I think my students got much more value.