I received several emails from my son’s science teacher warning of the upcoming evolution unit, clarifying the goals of the unit, and offering opt-out pathways. I’ve long understood such disclaimers and options as being due to the reality that evolution as it relates to humankind does not mesh well with some religious cosmologies. The concept of the current biological state of humanity being a phase in a billion-year-long slow-and-steady march of natural variation does not match what many people believe.

So what happens when we go to teach current events, American history, civics and government, or other social sciences and students or families want to opt out because it does not match what they believe?

This is emerging in numerous ways. Today is the last of the shortest month of the year, Black History Month. A few weeks ago there was a brief flare-up in Utah when parents sought to opt-out of any Black History Month lessons and activities. (On the same side of the coin, another school came under fire for promoting an “All Lives Matter” theme for this year’s Black History Month activities.)

Critical thinking temporarily prevailed in the above examples because the role and treatment of Black people in American history is well documented. And though it makes many people uncomfortable to acknowledge the horrific past and present treatment of BIPOC in our country, it is a verifiable truth with libraries full of primary source material in the form of things such as, oh I don’t know, state and federal laws, verifying the existence of racial oppression.

Where we have historical proof on the side of teaching Black history, things start to get a little fuzzier when history is made in the Internet Age. While anyone who claims “slavery never happened” would by and large be given the side-eye nowadays, disacknowledgment of verifiable realities is a hallmark of America in the 2020s.

When we as teachers encounter students who are believers of conspiracy theories, our go-to strategies for promoting critical thinking run the risk of backfiring. Articles such as this EdWeek piece and even this pretty solid article from BuzzFeed give the standard advice: teach about identifying valid sources to help kids discern real news from fake news; encourage kids to triangulate information by looking for consistency across differing, unrelated sources; and above all, demand quality evidence.

The problem I see is straightforward: All of the expected responses to those prompts are undermined by the very cognitive acrobatics that suck kids into belief in the first place.

Validity of sources? That means looking at the credibility of the writer, their references to their sources, etc. There is still tremendous subjectivity here. As an oversimplification, if one student is permitted to use info from Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to support a claim, why is another student questioned if they use info from Matt Gaetz? Extrapolate out to any other source of information, and the criteria I as teacher use to determine source validity could easily be used by a student to decide that some rando conspiracy-theory vlogger online is likewise valid. All of these determinations are colored by our subjective experiences and biases which can be dressed up as logic.

And real news versus fake news is no clearer. If there is the deep, practically religious belief that the “mainstream media” is lying, how can that belief be countervailed in discussions of source validity? I might believe X news source is valid for the very reasons someone else might claim it is invalid.

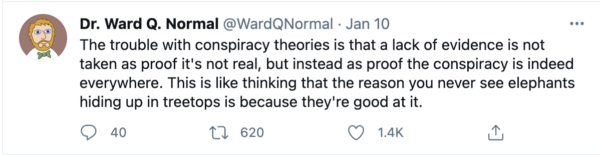

As for evidence: The essential mental acrobatics of conspiracy theorism rely on a fundamental logical fallacy, argumentum ad ignoratium, which is the belief that the inability to prove X wrong is proof that X is true. Further, if someone is capable of rejecting as invalid all evidence that contradicts their beliefs, they are left with no evidence proving themselves wrong and only their own evidence to support their claim.

We are in a critical thinking crisis in our country right now.

And it is not that schools are failing to teach critical thinking, evidence analysis, source analysis, basic logic, etc. It is that these live in the realm of logos, when the disinformation we are combating lives in the far deeper cognitive drivers of pathos and mythos. Just as ancient Greeks used their own threads of pseudo-logic to determine that thunderstorms were caused by an angry Zeus, when students or families are swayed by the underlying pathos and mythos, the current mythos of QAnon and other conspiracy theories can be (to the believer) bolstered by the very steps of critical thinking we teach in schools.

Teaching critical thinking is not enough to override such deep beliefs, no matter how absurd these beliefs may appear to non-believers.

EDIT: I do want to clarify: Opening this piece with a mention of evolution and closing with QAnon conspiracy theories is not intended to equate the two.

I’m glad that you are bringing up the topic of critical thinking and conspiracy theories. A lot of what I’ve been seeing on social media and in the news has been troubling to me. It seems like people are further and further retreating into their own echo chambers. Their beliefs are echoed back and there is little room for dissent or diverse thought. Teaching EL at the elementary level is amazing, because I work with diverse groups of students some of whom have not yet “Americanized” and so they bring in varied perspectives to issues. I strive to make sure every student feels comfortable speaking and sharing during our lessons on politics whether they are a Donal Trump supporter or hater. I feel that it helps to humanize those some may view as the opposition and promotes empathy. It also forces my intermediate students to consider different view points.

Fabulous.

BTW, I taught in Christian schools for four years before I broke into public ed. I taught evolution in my elementary science class. I told the kids–and parents–that they needed to know what science taught, whether they believed it or not. Not knowing just made them ignorant. I didn’t have anyone opt out.

Jan that is exactly what I teach when I teach argumentation. If you are going to “argue” in the intellectual sense, not the shouting-down-anyone-who-disagrees-with-you sense, you HAVE to know the other positions as deeply as you know your own…and ideally know a variety of other positions, as most issues are not binary.

Nowadays, we struggle as a society to muster the energy to deeply know our own position beyond the surface, meme, party-line…