On the drive home from school a few weeks ago, my middle son, at the time a first grader, said that from then on he wanted to be homeschooled.

My mind raced: Is he being bullied? Is he struggling to learn? What is happening that might make this otherwise happy kid want to be homeschooled?

As it turned out, it wasn’t that he didn’t want to go to his public school any more. He wanted to learn things that weren’t being taught in school: specifically, he was deeply curious about science. We came to the agreement that he’d keep going to regular school, but that we’d do some science experiments and learn some science at home.

This is the same boy who when I think about his education, it keeps me up at night. Not because I don’t trust his teachers or his school, but because I am concerned about what the coming years in school will look like for him.

This past year in my other job (teaching high school English to 12th graders) I had the opportunity to work with a young man who had spent his entire academic life with a label. Served by an IEP with all the best of intentions, this now-adult sat in his IEP meetings this year and articulated something that made my heart sink. He talked about how being part of the “IEP program” as he called it led him to assume that he was incapable of being successful. He described how he felt conditioned (his word, not mine) to wait for help because the message that he was not able to do it on his own and that he “needed help” was repeated loud and clear and often. Now possessing greater maturity, he was able to agree that everyone had the best intentions at heart, yet the collateral effect on him was that the “program” seemed to communicate to him that he was incapable. That became part of his identity. Rolled in with the other struggles he faced, a downward spiral ensued, and whether he would graduate from high school was in question almost to the very last minute. He did make it, though, and his reflections on his experience are shaping the way I think about my own son and what school can do for and to him.

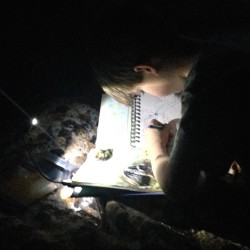

My son and science “homeschooling,” recording observations and classifying the flowers he finds in the backyard.

My own son, the one interested in science and art and math, has struggled with reading from the get-go. He’s entering the second grade next year well below grade-level standards in reading. He has struggles with speech and articulation and has attended speech therapy. He avoids reading, in English at least, because it confuses and frustrates him (he is in a dual language program, and his Spanish literacy skills in reading and writing far exceed his English literacy skills). When he gets a little older, I anticipate we’ll be seeking advice about screening for learning disabilities, out of the best of intentions but now acutely aware of what being a part of the “IEP program” (as my former student called it) might communicate to him about himself and his own potential.

When I envision his future, I can’t help but picture those high school boys I’ve dealt with for thirteen years: those ones for whom school is a frustrating cycle of failures and for whom the result is a bulky behavior file. These are boys who get in trouble for not sitting still, who balk at hours and hours of testing, and who’d rather have their hands in a car engine or in a garden or on a paintbrush than a Common-Core-aligned reader.

This son I’ve been writing about is the same kid who will sit and draw for hours, and when we do his science “homeschooling,” he stays engaged for what seems like eons for an almost-eight-year-old. This is the same kid who, when we work in the back yard, will pull weeds and shovel dirt until we force him to take a break. He has the patience to sit in a boat for hours waiting for fish to bite and the focus to build art projects out of our recycle bin with clear purpose and clever engineering. But if he continues reading below grade-level, what will his school experience end up looking like? Out of the best of intentions, heaps and piles more of the very things that frustrate him and remind him of his struggles. Out of the best of intentions, legal documents and labels that we adults in the room might assume he “won’t understand,” but that will mean more to him and his identity as a student than we probably realize.

That 12th grade student I mentioned above is a musician. This year he has found personal purpose in teaching music lessons to younger kids… and it is no coincidence (in my opinion) that when he started teaching music lessons, his attitude about himself as a student started to evolve. Certainly many factors were at play here, but I think a big part of it had to do with an identity shift. Maybe it was that no longer did he see himself as someone who can’t learn, but he realized that he is someone who can teach. To that point, his entire growing-up had been focused on remedying those things the data said he couldn’t do, at the dramatic expense of those things he could.

As a parent, I now realize that though there will be things that my son’s report card will tell me he can’t do, I need to remember to keep a focus on encouraging and cultivating those things he can do. As a teacher, I now realize that I sometimes inherit students who’ve been in a system focused only on fixing their can’ts, and it will serve all of us well if I pay good attention, however I can in my power, to cultivating their cans.

Mark, the fact that your son is doing well in Spanish literacy vs. English literary is worth exploring. Spanish is a totally phonetic language. And as long as the Spanish empire reigned, the court literally kept rule over the language, maintaining consistency throughout the Latin world–although that tight rule over the language disintegrated after the colonies gained independence.

English, of course, is not a phonetic language even though it has phonetic elements. And it’s hardly consistent from one part of the English-speaking world to the next. Just think of the differences between Australian and Irish and Texan English!

If I had your son in my class, I would start with what your son does well and teach him all the English rules of phonetics. I would also explain that English is not like Spanish–there are lots of exceptions to the rules. It’s true, English is harder to learn than Spanish. According to my Spanish teachers, most students can learn to read Spanish in about a month. They said that “reading” classes in elementary schools in Mexico focused on comprehension and analysis, not decoding.

I wrote a grammar book called Elementary English that I’ve posted online at Kragen.net for free. (Look under “books.”) In the introduction I explain why English is such a mess. It may help your son understand why English is so confusing. It is not his fault!

Great post, Mark; thanks for sharing. I also have a child who struggled with reading, went top our district’s “special ed preschool” and had an IEP. He’s going to be a junior next year, and even though school is still a struggle, he’s doing pretty well. I’d say it gets better, but it really doesn’t. School was designed by and for students who enjoy and excel at school. Not by those who don’t. Hopefully that will change, but until then, IEPs are the best idea we’ve come up with.