At the beginning of this year I interpreted at a parent-teacher conference for a Ukrainian third grade student. He was a second year English Language (EL) learner. The teacher praised both his academic and social progress. His mother listened politely and nodded at the appropriate times. At the end of the conference, the teacher asked if she had questions. The mother asked, “Why is my son getting so little homework?”

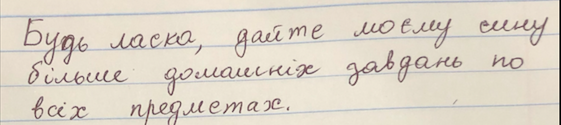

Please give my son more homework in all subject areas.

More than a decade ago, Alfie Kohn wrote, “The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing.” Stanford published a study in 2014 showing the pitfalls of homework. Other studies cropped up. All detailing the ineffectiveness and negative impacts of homework. With homework steadily gaining a bad reputation, my district and school decided to encourage teachers to decrease the amount of homework given to our K-5 students.

Parents noticed.

As I continued to interpret for Ukrainian and Russian speaking families during parent teacher conferences, all questioned the lack of homework. A few weeks ago another third grade student walked into my room with a note for me to translate. The mother requested more homework for her son. On reading the note, I could not hold back a smile, asking, “Do you know what your mom wrote?” His shoulders slumped and he nodded. An expected response.

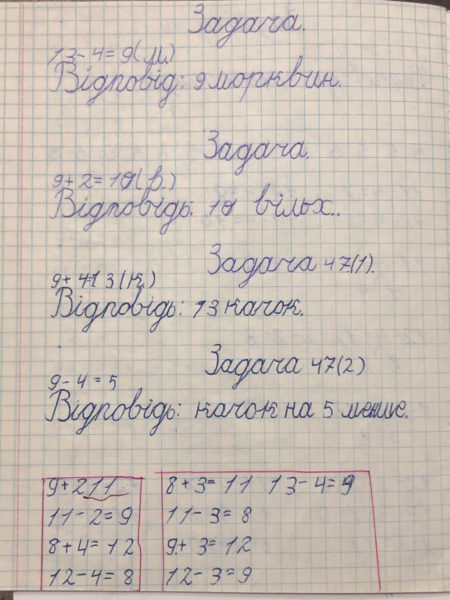

In Slavic countries parents measure the effectiveness of a teacher based on homework. As a first grader in Ukraine, I spent a lot of hours and tears on my homework. I used a pen in my notebook, so I needed to draft my work on scratch paper before copying the final version into the notebook. Mistakes needed to be carefully scratched out with a razor blade. I also spent a lot of time memorizing poems to recite.

A disconnect exists between the Slavic parent’s perception of homework and the American teacher’s. I interpreted at multiple parent-teacher conferences, where teachers explained how the children are still learning the English language, so homework should not be a primary focus. Each time Slavic parents insisted on their children receiving extra math problems and reading passages. They want their children to catch up quickly.

It would be wrong to think conflicting perceptions of homework only affect our school’s Slavic population. Families from other ethnic backgrounds are known to thank teachers, who give greater amounts of homework, comparing them to teachers who gave less in the past .

Some parents gave up asking teachers for homework and now create their own.

What is the right answer in this case? Should teachers give less homework or more? How do schools share anti-homework research with parents? Moreover, how can they get parents on board with the decrease in homework with cultural and language barriers in place? How can schools better communicate information about the research base and rationale?

I see no easy answers. I am reminded of a personal story shared with me by a past EL student. She attended schools in Washington state where she received almost no homework. Her first quarter at college ended in failure.She said as a high school graduate she had not developed a concept of homework and so struggled with deadlines and time management. She did not take homework seriously. Now as a student in Central Washington University’s teaching program, she finds herself defending homework to professors and peers.

Then, I think of the illiterate parents at my school both in their native language and English. Without any type of educational background themselves, how can we expect these parents to help their EL kindergartners with homework? They love their children but are unable to help with school work at home. Not only is this helplessness demoralizing, but they must make a choice: a) handle the situation on their own by either seeking outside help or ignoring the homework, or b) gather their courage and ask assistance from the teacher, admitting to their illiteracy.

Other parents of EL learners, while not illiterate in their native language, struggle with English. My first year in the United States, my mom and I spent a lot of late nights at the kitchen table with my homework and a Russian-English dictionary. Again, many tears were involved. At this point I need to interject and say, I’m not bitter about the frustration I experienced over homework both in Ukraine and the United States. I barely remember this time and instead of making me upset those memories make me smile. More than the struggle of completing the homework I remember my mom’s patience and love. After helping me with my homework she would leave that night to clean offices. When I asked her about those nights from the past she said, “But you handled it, and I learned English terminology.”

I think we can all agree that the conversation isn’t–and shouldn’t be–over. What do you think? How is homework perceived by your parents and communities?

I do big projects with my students with steps along the way to help them build time-management skills. (“You need to pick your topic and find print resources this week. You need to continue to find and take notes on print resources this week. You need to find and take notes on web resources this week. You have two weeks to organize and write the text of the body of your research. You have a week to write the introduction and conclusion.”) I give lots of classroom and computer lab time so kids can get the work done at school. Plus I coordinate with the school librarian so she supplements my lessons and gives additional time while my students are in the library.

BTW, I grade written work before the class is allowed to move onto the best part–creating the presentations. That’s the part they look forward to, and they know they aren’t allowed to start their presentation until I’ve approved the written work.

Most students finish most of their work in school. There are a few who need to load their work onto a flash drive to finish at home. But everyone gets done.

Years ago students did all their projects at home, which drove parents crazy. Kids had music and dance and theater and sports. And then hours of homework. Now my parents LOVE the fact that I teach time-management within the school day and do everything in my power to help every child finish their work at school.

I teach 5th grade in a Highly-Capable classroom. My goal is very little homework.

Hi,

Just a quick question for you. What do you have students do who are done early with their projects?

Thanks!

I have also experienced some parent reaction to my homework policy (which is that I don’t typically assign written/typed homework unless my students have been absent or do not complete the work during class; I do sometime assign home reading during literature units… I teach HS English).

The vast majority of parents have no reaction, but there are rare few who have accused me of failing to prepare their child for college because I do not assign mountains of homework. I struggle with the societal perception that being busy means learning is happening, or even that being busy is a good thing, for that matter. I do observe that teachers who assign reams of homework often prioritize “getting through everything,” while those who don’t assign homework tend to focus on “learning as much as possible.” That’s a HUGE overgeneralization on my part, of course, but a trend I’ve observed, nonetheless. AND that is about the teacher’s priority, not the parent’s.

I definitely agree with your aversion to assigning mountains of homework. If homework does not support and extend learning then it is just busywork. Our students are smart enough to know the difference. If we make the choice to assign them homework, then it needs to bring value to their lives otherwise they lose respect for the educational system.