Perhaps you’ve heard the story of Phineas Gage? In 1848, while packing explosives with a 43 inch long, 1.25 inch diameter iron tamping rod, an explosion sent the rod completely though his skull. He was never quite the same, but he miraculously survived.

Though this analogy might stretch the bounds of good taste, I wonder how I would ideally position my body to absorb the impact of using students’ test scores to evaluate me as a professional educator. It seems completely absurd to have this measure included in the Senate education bill.

The Seattle Times reported that the organization Stand for Children collected over 20,000 signatures to get this provision into the bill. The claim is that the teachers union and other lawmakers who oppose the bill are putting the needs of teachers before the needs of students.

What exactly are the needs of teachers being put before the needs of students? Is one the need to be treated fairly and professionally? That seems important. What is the need of students that is taking the back burner? Is it the need to have an engaged, highly educated, well-respected professional teacher working with them day in and day out, making a difference in their lives? That seems important too. Can’t we have both?

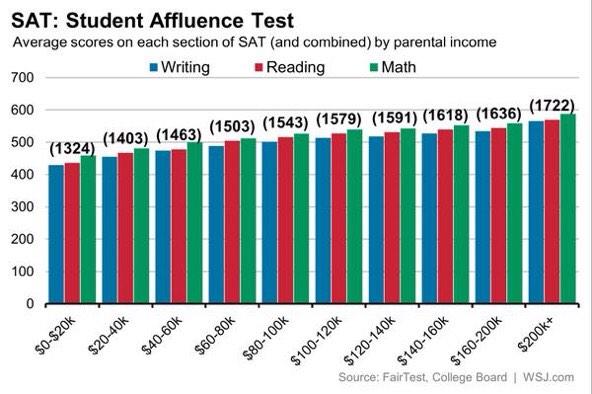

Though this is a scathing indictment, test scores can be predicted by poverty. This is not the fault of teachers, however. This is a problem that exists within the larger context of our society and must be solved within that context. It will never be solved at school, though education is absolutely a powerful force for change.

How does evaluating teachers on test scores make sense when this correlation has such a profound effect. Shouldn’t we motivate the best teachers to teach the students with the greatest needs? Tying evaluations to test scores de-incentivizes what we know needs to happen.

Add to this that there are only certain subjects that are tested in each grade level. It is simply not equitable to teachers to have evaluations based on subject matter tests when students do not have to take tests in all subject areas. How will a music teacher or an art teacher be evaluated? All teachers fall under the same contract, but they don’t all do the same exact jobs.

Finally there is the issue of the student scores themselves. The “Economic Policy Institute, Problems with the use of student test scores to evaluate teachers: [reports that Value-Added Measures] estimates have proven to be unstable across statistical models, years, and classes that teachers teach. One study found that across five large urban districts, among teachers who were ranked in the top 20% of effectiveness in the first year, fewer than a third were in that top group the next year, and another third moved all the way down to the bottom 40%. (Scott McLeod) ”

So there’s that… they don’t work to evaluate teachers.

So what we are left with is a testing system that costs millions of tax-payer dollars, to administer hundreds of tests (of varying degrees of high stakes) to each student over the course of their K-12 years, taking away thousands of hours of real instruction to collect a massive amount of data that says very little.

If you want a system that works to build teacher responsibility and capacity this is the wrong way forward. This is a case of using the stick when it is a carrot we need. If it’s going to be the stick, or an arrow, or a 43 inch iron tamping rod headed towards me at a high velocity, I’d like to get out of its way. If it’s carrots, then I’d like to have a seat at the table.

Pingback: Common Ground | Stories From School

Pingback: The Stories We Tell and the Stories They Hear | Stories From School

Nice post, Spencer. I agree that using the scores is an ineffective way of evaluating teachers. I wonder what our education system might look like if we started evaluating teachers — not on the data itself — but how the data is used to inform instruction.

When I was in public school in Chicago, my teammates and I would regularly convene around student work, discussing different aspects of different samples, and centering — as a team — on what “proficient” work looks like. I think this not only made me a better evaluator, but it also organically fostered discussions about practice. We were able to discern between naturally talented students, as well, and trends that hinted towards effective instruction. I think we all grew immensely as professionals, not from the scores themselves, but from the way in which we used our data to continue to reach our students.

It’s somewhat I ironic, but our most successful year of test scores, as a team of six, was in my final year there, when all of us had developed some solid processes for planning and reflection. It seemed that, when we weren’t necessarily evaluating ourselves on outputs, but more so committing to a process, our test scores and student work improve drastically.

Thanks for your post!

Great hook, Spencer!

Robert E. Slavin, the Director of the Center for Research and Reform in Education at Johns Hopkins University, wrote an article recently called “Accountability for the Top 95 Percent” (http://www.huffingtonpost.com/robert-e-slavin/accountability-for-the-to_b_6307892.html). He argued that rather than holding teachers accountable for student learning, we should hold PROGRAMS accountable.

BTW, I highly recommend “The Best Evidence In Brief” email news (http://www.bestevidence.org/subscribe.cfm) as a great way to keep up on research-based data.

Great post, Spencer. I was somewhat in favor of the waiver bill last year, mostly for pragmatic reasons, but I’ve come around to your point of view. The sky didn’t fall when we lost the waiver and it won’t fall if we keep losing it. And we still have an evaluation system that’s fair.