Don’t get me wrong, I love to teach Black history. I just think it needs to happen throughout the year.

Last year I taught early American history. I introduced the topic of slavery by first explaining that slavery was an accepted way of life throughout the world for much of human history. Prisoners of war became slaves as well as kidnapped members of rival tribes.

In the 1400s in the New World, so many enslaved Indians died that the Spanish priest Bartolomé de Las Casas—who felt bad for the Indians—suggested replacing them with Africans. He later regretted his recommendation when he saw how badly the African slaves were treated.

Throughout the 1700s, ships from northern US colonies sailed to the coast of Africa to purchase slaves from African slave traders.

So much of that brief summary surprised my students. Blacks were first brought as slaves to the New World to replace the Indians? Northerners were involved in the slave trade? Africans captured other Africans to sell them as slaves?

That last especially horrified them. “How could they do that to each other?”

I told them to stop thinking of “Africans” as all the same—it was like thinking of “Europeans” as all the same. “Did Germany and France ever fight each other?”

“Oh. Yeah.”

In the US colonies, slavery first started when Dutch traders brought 20 black slaves to Virginia in 1619. (By this point we’ve had the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, and English all involved in the African slave trade.)

By the 1660s Virginia defined slavery as “servitude for life.”

Then, in a complete break with historical precedent, all children of a slave mother, whoever the father might be, were declared slaves, so slavery became an inherited condition.

White men had children with their female slaves and kept their own children as slaves, which my students found appalling. “How could you do that to your own children?”

After a few generations there were many light-skinned slaves in the south—but however tiny a fraction of their ancestry was black, they were still 100% “colored” and still 100% slaves. This concept made no sense to my students, many of whom are mixed-race. (Lord knows, I hate that designation, too.)

By the end of the year we had traced the stain of slavery through the Declaration of Independence (where Jefferson’s polemics against it were removed) and into the Constitutional compromise.

Of course, this year The New York Times Magazine published “The 1619 Project,” which I eagerly anticipate using with my class. Next year.

This year I am teaching the 20th century in America. I started with the history of lynchings in this country, sharing information about the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. My fifth graders were shocked. I went on to read them the story of Ida B. Wells, a Black journalist and activist who wrote and spoke about lynchings from the 1890s to the 1930s. Her life so inspired my students they applauded her!

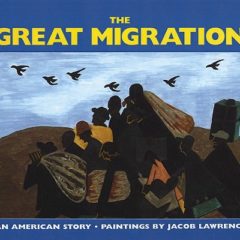

After the unit on World War One, I read aloud Jacob Lawrence’s critically acclaimed picture book The Great Migration about African-Americans who headed north after the war.

As part of the lesson on women’s suffrage, I shared dozens of stories of Black and White women inventors and entrepreneurs from the 20th century and asked what were the odds of them being successful without first gaining the right to vote?

While teaching about the Depression, I made it clear that Black tenant farmers were hit especially hard. At the same time, we discussed the rise of the KKK (again) in the 1930s.

Our next unit will have us comparing how the Black soldiers were treated during World War Two versus how they were treated once they got home and how that discrepancy helped drive the Civil Rights Movement. I will also explain redlining from the 30s and how that affected wealth creation in the housing boom of the 50s, driving a widening economic gap between Whites and Blacks.

Honestly, I don’t think Black history was ever intended to be crammed into just one month. Carter G. Woodson, the “father of Black history,” hoped the time would come “when all Americans would willingly recognize the contributions of Black Americans as a legitimate and integral part of the history of this country.”

I believe, if you are teaching US history, you ought to be teaching Black history all year.

That means a lot, coming from you, Mark.

You’re doing the good work! I love the way you’ve framed the lessons/discussions you have your kids engaging with.

I couldn’t agree more! Teaching Black history as a separate thing almost seems patronizing. I do think you will find that the 1619 curriculum is not entirely trustworthy. The sections that deal with the effect of slavery on the descendants of the enslaved in the 19th and 20th centuries is thought to be solid, but the section on the Civil War era is iffy and the claim that the Revolution was fought to protect slavery is pretty thoroughly debunked by reputable scholars.

I appreciate the comments. And thanks for the heads-up. I will definitely keep your comments in mind as I look over the 1619 curriculum this summer.

Loving the links. Thanks, Jan!