My first two years of teaching, I commuted to work—45 minutes one way, an hour and a half the other. My gas bill was insane and I was constantly stressed out from the traffic. I wanted to move closer to my school, but didn’t really want to live in Kent. Although I loved the staff and the students, I knew I wanted to eventually work in a more urban school. Commuting was the norm for most teachers in our building, and a majority of my colleagues drove in from surrounding cities. We’d joke about the benefits of living out of district—time to plan in the car or going to a bar without worrying about running into parents. But, I always felt the drawbacks outweighed the benefits. I was so exhausted I didn’t feel like I was doing my best teaching. I barely attended after-school activities like dances, football games or musicals. I felt like I wasn’t supporting my students enough and only had a surface level understanding the community’s values.

Deep down, I knew that living so far away from where I taught was counter to my belief system. I grew up as the kind of missionary kid that actually lived in the village my parents worked in. My parents home schooled us so that they could integrate their ministries into our daily lives (that meant at age 8 I was helping deliver babies in the prenatal clinic my mom built in the garage). This is why, after two years at Kentridge High School, I eagerly accepted a job in Clover Park School District just ten minutes from my house. Now, I teach at Lincoln, eat my way up and down 38th street (shout out to Vien Dong, Zocalo, and Dragon Crawsfish!), shop at Cappy’s and the 72nd Fred Meyer, and live on the Eastside of Tacoma. I love it.

I believe in neighborhood schools.

I believe in living and teaching in my neighborhood school.

A strong neighborhood school has the potential to change lives. It can be community-oriented, a center of support for families. It’s the community listening as Clover Park HS seniors describe how they tried to change the world through their senior project. It’s Abe’s Golden Acres providing one ton of food for the Eastside of Tacoma during the summer. It’s the SOMA church donating toiletries and snacks for the Football team. It’s The Grand Cinema sponsoring a Film Club after school. Successful neighborhood schools are thriving hubs that facilitate strong community-school partnerships that promote real world learning experiences for students.

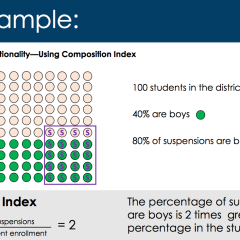

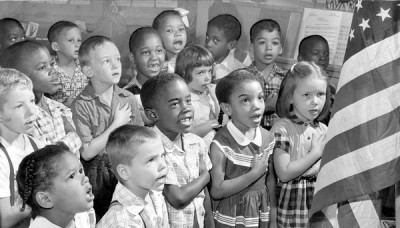

I find myself extremely excited about neighborhood schools that are an integral part of their community and that reflect the racial and cultural makeup of that neighborhood. But the nature of intersectionality prevents me from ignoring the overlapping venn diagrams where race and class meet school and housing policies. Because anyone who doesn’t live under a mushroom can see that the neighborhood school reflects the people living in the ‘hood. So we end up with whiter or browner schools directly reflective of historical housing practices (redlining) and current housing “choice” (aka white families fleeing the urban core).

As a result, our segregated neighborhood schools reveal an increased concentration of the have and have-nots. In my mind, the real issue is the concentration of poverty that accompanies the neighborhood.

One thing I’ve always appreciated about many high-performing charters is that they are neighborhood schools. Many public charters are serving a traditionally marginalized, high poverty population. Programs like KIPP or Greendot are a response to long neglected neighborhoods and communities. And their students are thriving. The anti-charter crowd forgets that segregation already existed in these communities and that the charters went into rejected communities, targeted children that many believe couldn’t learn, and said they were valuable and could achieve. Charters schools don’t promote school segregation. They offer a solution (note: I did not say the solution).

So What?

If we want great public schools for all students then we need to be honest with ourselves about our current conditions. We need to recognize that the current housing and school policies work together for the betterment of some schools and neighborhoods and not others, and with that understanding we can do better. We need to prioritize. Is school choice most important? Does the demographic makeup of the student population really matter? Do we fight to desegregate our schools? Do we work to decentralize concentrated poverty? Do we invest in making amazing neighborhood schools regardless of the makeup of the neighborhood? All of the above?

Now What?

There is so much more to be said or explored. But for now, I want to end with a thought from Korbett Mosesly on my initial post.

“What if we started from the premise that culturally affinity neighborhoods are ok. It is the racial mismatch in educational leadership/teacher and their students that may be an issue if there is a lack of open dialogue and understanding. It’s a lack of equity in resources to provide fully funded educational programs that is an issue. It’s a concentration of intergenerational poverty and a lack of people be willing to have hard conversations about systems of oppression.”

Let’s continue to have those hard conversations.

By Tom White

By Tom White

This post is the beginning of a series of posts I will write about 21st century school segregation. I want to start by acknowledging a few factors that influence my perspective and shape my writing.

This post is the beginning of a series of posts I will write about 21st century school segregation. I want to start by acknowledging a few factors that influence my perspective and shape my writing. By Tom White

By Tom White