The education funding bill from the Washington Senate, SB 5607, includes a section prohibiting teacher strikes.

When I heard about this provision, my first question was, “What does the right to strike have to do with an education budget?”

The answer, of course, is nothing. Look at the League of Education Voters’ comparison chart of four funding proposals side-by-side: the current state education funding levels, Governor Inslee’s Education Funding Proposal, the Majority Coalition Caucus Education Funding Proposal (SB 5607), and the House Democrat Education Funding Proposal (HB 1843). There is no mention of right to strike in any of the other proposals. That’s because having the right to strike has nothing to do with funding.

So I double checked. Was this Senate bill actually a funding bill? Of course it was. Up at the top of the bill, it says it was “referred to the Committee on Ways and Means.” It’s a bona fide budget bill.

Some senators decided that—on the way to rewriting how to fund education—they would also add this change in how teachers can protect themselves.

Take a minute to read the text of this section.

PART XI 2 PROHIBITING TEACHER STRIKES

NEW SECTION. Sec. 1101. The legislature finds that, like other state and local public employees, educational employees do not have a legally protected right to strike. No such right existed at common law, and none has been granted by statute. The legislature further finds, as have numerous trial court decisions and the Washington state attorney general in AGO 2006 No. 3, that any argument that a right to strike is implied by the absence of a provision in chapter 10 41.59 RCW is wrong. The legislature intends to provide greater clarity to parents and school districts by prohibiting strikes, work stoppages, or work slowdowns or other refusal to perform official duties.

NEW SECTION. Sec. 1102. A new section is added to chapter 41.59 RCW to read as follows:

Nothing contained in this chapter permits or grants any educational employee

- the right to strike,

- participate in work stoppages or work slowdowns,

- or to otherwise refuse to perform his or her official duties.

(Highlighting and bullets are mine).

I don’t know about you, but when I read this section, my heart just stopped.

Right now I am in the middle of teaching about colonial America to my class of fifth graders. We talk about indentured servants who came to America. They paid for their passage by working for their masters for seven years. Essentially, for those seven years, they were the equivalent of slaves. They had no rights. If they were lucky, they had a good master. If they were unlucky, they didn’t. But they had no recourse. They were stuck for those seven years.

No right to strike? No work to contract? (That would definitely count as a work slowdown!) No saying no to evening work or early morning or after school meetings? (A principal could call those “official duties.”)

No effective way to make our voices heard?

I read that Senate bill passage and immediately felt like an indentured servant. Like I had traveled back in time to the 1600s.

No, thank you!

I find it interesting that the senators who wrote this bill said their intention in including this section was to “provide greater clarity to parents and school districts.” They act as if teachers’ strikes cause the greatest problems for parents and districts.

True, parents have it hard when teachers go on strike. Their children aren’t in school. They have to arrange childcare. I’ve been amazed, though, at the level of support many parents give striking teachers—perhaps because they know best what the teachers are doing in the classrooms with and for their children.

If the teachers are striking against their districts, I am sure their districts are deeply unhappy. But I guarantee the teachers are deeply unhappy too. Teachers don’t go on strike lightly. Whenever I read about districts out on strike, I think about how much time those teachers must have spent working through every other option to come to an agreement. I think about how they have struggled through other procedures, without success, to arrive at the difficult and taxing step of striking.

I don’t buy the legislature’s sly claim, though. My district has participated in two “strike” events in the 28 years I’ve lived in Washington. Neither time was our action aimed at our district.

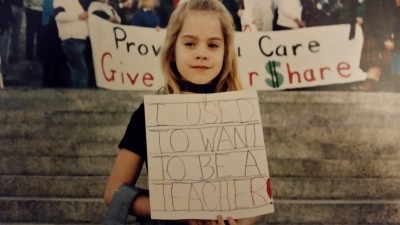

Both times we protested against the legislature.

By the way, both times we walked out for a one-day strike, we had the support, not just of the parents in our district, but of our administration as well. After all, our district administrators were just as upset with the legislature as the teachers were!

I think the senators added this section to their budget to protect themselves! They are threatened by the media coverage when masses of teachers show up on the Capitol steps.

I say we need to keep showing up until we get the issues resolved. Because that’s our JOB. We are, after all, educators. We have an obligation to educate, not just the students in our classroom, but the adults who impact them. The school board. The public.

The legislature.

Because I went back to read the beginning of the Senate bill, I discovered this opening line: “GOAL. The goal of this act is to improve the educational outcomes for all students.”

That’s a great goal! We promise to stand right there next to you, senators, holding your feet to the fire, making sure you live up to that commitment.

Yes to both the post and to Mark’s comment. I really appreciate how you lay out that the right to strike and a budget are NOT related to each other at all!

Clearly, the inclusion of the strike provision is a deliberate attempt to silence teachers and put us “in our place.” You are right about the infrequency of strikes… and usually when they do happen, it is after a long, long effort to avoid that very action.

If someone can clearly articulate a direct connection between “making strikes illegal” and “fully funding education,” I’ll gladly change my mind. Despite how people want to cast strikes (being about greedy teachers being the go-to line), the reality is this: schools are underfunded, if we want high quality teaching we need to be willing to pay for high quality teachers. In my career I have seen more than a dozen very good teachers leave for less stressful, higher-paying, less vilified jobs. To all those who say “if you’re not happy and you’re so good at what you do, go get a different job,” my question is this: do we really want to have a teaching corps comprised of folks unqualified or unmotivated to find “better” work elsewhere? To convert the cliche: we won’t get what we don’t pay for.