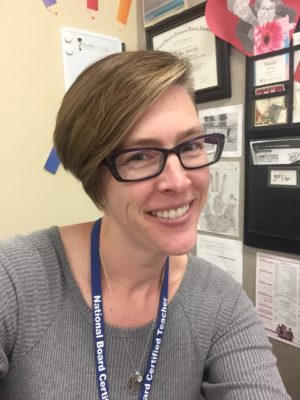

By guest bloggers NBCT Heather Byington and NBCT David Buitenveld

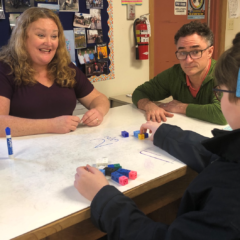

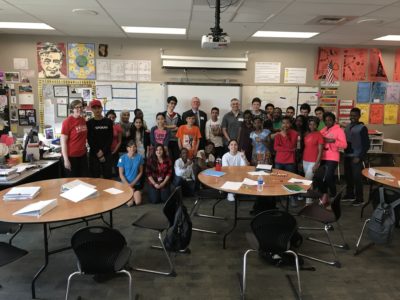

What happens when a middle school math teacher and an elementary teacher co-teach math to 5th graders for a quarter? David Buitenveld, a middle grade math teacher leader who recently received his National Board Certification, and Heather Byington, a veteran elementary teacher leader and long-time NBCT, discuss their journey of collaboration, with the Architecture of Accomplished Teaching as the common path.

David (newly-certified NBCT and 5-year middle level math teacher):

During my NBCT journey last year, I spent more time than previously with the question “what do you know about your students?” and the answer, embarrassingly often, was “not that much.” Keeping that question present (a key takeaway from the National Board process) led me to realize that although I understood the mathematical ideas students encounter in elementary grades, I didn’t have knowledge of their lived experience of 5th grade, and how that experience affected their transition to middle school math. Co-teaching with Heather was a chance to experience 5th grade math and see their world in action.

Heather (long-time NBCT and 20-year teacher):

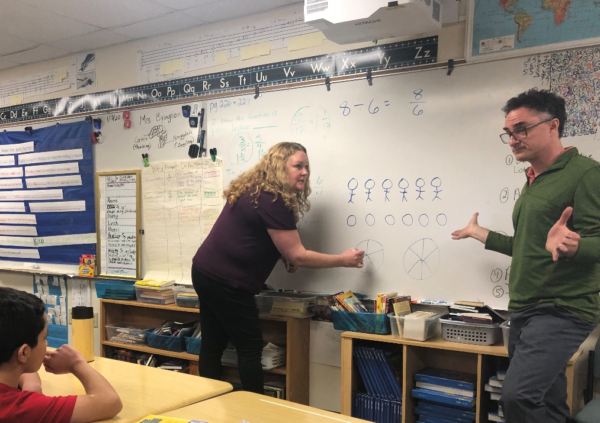

When David asked to co-teach math in my classroom, I wondered if it would be intimidating to work with a math expert. I quickly realized that he is more skilled at constructing inquiry-based discussion around a math concept, while I feel more comfortable with direct instruction. My first attempt flopped, while he watched! But David jumped in and helped me make more sense of the math for students! I learned from him that it’s okay to try new things and have them flop. When kids see that I try, fail, and keep trying, they’re willing to keep trying too.

David:

Continue reading