Last week I introduced the year’s big research project to my class. My students are so excited!

In addition to learning about a conflict in the 20th century, individuals and teams will analyze causes and short- and long-term effects of their conflict.

The first step was to pick a topic that fit within the parameters. It also needed to be a manageable topic: for example, the Bus Boycotts instead of the Civil Rights Movement.

The second step was to find good resources, both print and online.

We talked about where to find good books: in my room, in the school library, in the public library. One student shared a couple of books her team had found in the school library for their topic—the Tet Offensive. We used the index in each, and in one book we found not just a section about the Tet Offensive, but also information in following sections about consequences of the offensive. My student’s eyes got big, and she said, “We really lucked out on this book!”

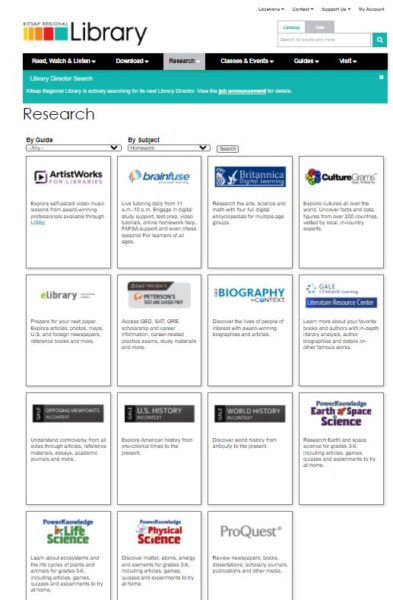

As we talked about finding online sources, I said to focus on .gov and .edu and sometimes .org sites and, even more importantly, to look for who sponsored the site—NASA, Johns Hopkins, the American Medical Association. “You want to know who is standing behind the person saying you can trust that they are an expert.” I also explain about “gateway” sites. For example, our local library provides links to vetted sites for students to use. So does the Smithsonian.

(“Is Google.com a good source?” “Google isn’t like a book or an article. It’s a collection of a trillion or more books or articles! Saying “I found my information in Google.com” is like saying “I found my information in the library.”)

I told my class to avoid most .com sites, explaining that “.com stands for commercial.” (It was originally the designation for business sites, which doesn’t necessarily mean bad content, it’s just not usually academic or educational content.) I added that a student had come to me once asking if a site was legit. The World War II information looked good, but he couldn’t find the sponsor for the site. I went to the home page. Turns out the site was for a used car dealership, which my students found hilarious. Apparently, the owner of the dealership was a bit of a history buff, but we all agreed we wouldn’t use his site as a trusted source.

Having students read and take notes on books before they go to online sources gives them a good cross-check for information, too.

That’s a quick snapshot of how I teach students to evaluate sources.

It’s not enough, anymore.

I’ve been teaching in a world of the library and the internet.

Now that more and more people are turning to social media for information, I need to start teaching about social media.