How many of you watched The Queen’s Gambit? Lots of hands up? Good.

I had a visceral response to two scenes. In the first, highly-ranked American players from around the country played chess in a high school gym. There are a few people scattered in the stands, some dozing. No reporters. No cheering fans.

In the second scene, a similar group of chess players was in a swanky hotel in Paris. There were reporters and attentive spectators.

The images stuck with me long after I finished the show. I thought about that American game and how different the place would have looked if it had been a weekend varsity basketball game.

Our nation applauds talents and gifts in sports, building gymnasiums and stadiums, supporting teams with booster clubs and cheerleaders.

America, though, has a strong anti-intellectual streak. It’s been that way all my life, but in my view, it seems to be worsening in recent years. That anti-intellectual bent reaches all the way into our educational system.

Jonathan Plucker, a professor at Johns Hopkins University who focuses on making accelerated education more accessible to disadvantaged students, says, “The ideology is turning against excellence. We are institutionalizing anti-intellectualism, and that has long-term implications for us.”

Across the country, instead of expanding gifted/Highly Capable programs and making them more accessible, districts are dismantling them in the name of equity. There are concerns that some districts are softening standards for all in the name of closing the achievement gap. I say, let’s make education more challenging and enriching for more of the student population. That’s actually the intent of the WACs.

Montgomery County in Maryland … used to depend on parents to apply for elementary gifted-and-talented spots, which filled a handful of magnet programs with about 750 mostly Asian and white kids. Once educators began universal screening of all students, they found thousands of kids, many of them black and Latino, who would benefit from accelerated education and won seats through an assessment of report cards and tests. Since the 2016-17 school year, the program has spread to four additional magnets and more than 40 elementary schools with classes serving over 4,000 kids, says Kurshanna Dean, supervisor of accelerated and enriched instruction.

Equity for Highly Capable (HC) students means those students should be working hard every day to make appropriate annual gains based on their abilities. Isn’t that what we expect for every student? Unfortunately, “the ideal, that every student’s learning should be maximized, remains elusive, and children who need more difficult work and greater rigor are increasingly invisible” (Fordham).

When colleagues of gifted-guru Roger Taylor say they don’t believe in gifted education, Taylor tells them they better dismantle their varsity sports. Stop holding pep rallies. No more intermural games. Quit handing out jackets and letters to identify the members of the teams.

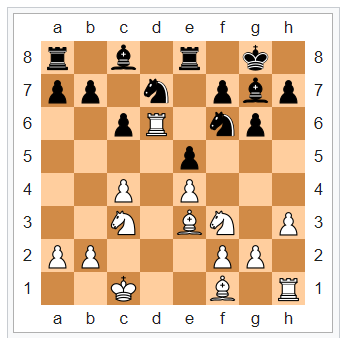

Picture it. Can you imagine giving out jackets and letters to members of the Philosophy Club or the Model UN Club or the Chess Club? Holding pep rallies for their competitions? Busing players and cheerleaders to away games? Prominently displaying their trophies by the front entrance of the school?

Why is it celebrated to be superior in athletics but elitist to be superior in academics?

I can’t highlight how importance of this type of thinking. When I entered high school, I really wanted to take Honors English classes. However, I was so intimidated by the reputation of “honors” and my EL status that I decided to take a regular English class. I learned a lot but it was not much of a challenge, and I was often frustrated by how many of my classmates found the class boring and didn’t take it seriously. The following year I took 10th grade honors English and it was the best decision of my life. I am SO happy that I did.

Honestly, I have so much more that I would like to share on this subject. I had a few months short of a full year of schooling in Ukraine before moving to the U.S. (never attended a day of daycare or kindergarten or preschool). When I moved here, my parents placed me in third grade as was appropriate for my age (yes, I never attended second grade). Mathematically, I was on par with my peers. I could also write in Ukrainian in both block letters and cursive. Trust me, I was no genius, the standards are just much, much higher there. Why can’t we expect our students to do the same?

When I taught the HC at the middle school, I never turned students away who wanted to attend my class.

I told administrators, “Stop calling it gifted or gifted and talented or highly capable. Just call it the ridiculously hard class. Then see who signs up!”

As a teacher who typically works with on level or struggling students, this is not something I have spent a lot of time thinking about, and I appreciate you giving me some food for thought. I like your frame of bolstering these programs for all, rather than dismantling them in the name of equity.

My next wonderings would be how to make courses in High Cap and similar honors or higher level courses more accessible to all students? Given disparities in who takes AP courses across the country, for example, I would want to make sure that “intellectual elitism” is available for all and from an early age.

I love your idea of letter jackets and trophies for academic, as well as athletic achievement! 🙂 What would it look like if we really celebrated academics in the same way we celebrate athletics?