Find Your Joy: Lessons from the Tennis Court

Coaching tennis this year has been a blast. We know all too well the seemingly insurmountable challenges and stresses of almost every aspect of our educational system. For me, hitting the tennis court after school these past few months has been life giving.

The news feels heavy (it always feels heavy) so instead of diving into Uvalde, or Roe .v Wade, or the two year anniversary of George Floyd’s death, or the myriad other societal catastrophes, (which I do plenty on my Instagram) I’m going to practice some self care and focus on something that brings me joy.

Taking a leaf from Lynne’s book, here are some lessons that being back out on the court has taught me. Coaching, is of course, a kind of teaching, but I’ve been in awe of the broader gifts hitting this little yellow ball has given me.

- You can’t win ‘em all

No one wins 40-0, 6-0, 6-0. Not our girls who make it to the state tournament or even the pros. You’re going to give up points. In your classroom, you can do everything “right” and kids will still disengage, put their heads down, socialize instead of reading, or fail a class.

There’s often a top down narrative that if only teachers made lessons more engaging, built strong relationships with their students, or called home, then all students would want to show up and succeed. But, what if you’ve done all that? You’ve thoughtfully planned lessons instead of just recycling from years past, students know they can cry with you about a breakup, and you’ve connected with all families, but students still fail?

Some things are simply outside of our control. Sometimes, your opponent aces their serve. Sometimes, a student is experiencing trauma at home bringing their focus to safety, not homework.

This doesn’t mean you don’t do everything you can to get 100% of your students to succeed, 100% of the time. Of course you do; this is what good teachers strive for. It doesn’t mean you don’t practice serve returns and just expect to lose points.

You’re just not going to win 40-0, 6-0, 6-0 or ace every lesson, every student, every day, 180 days a year.

- Go easy on yourself

When you lose those aforementioned points, you have to shake it off.

It’s inspiring to watch our girls lose the first set, but battle back to win the next two, all because they didn’t give up or let the mistakes get to them. Tennis is an intensely mental sport and it takes some serious toughness to not let the double fault or shanked backhand throw you.

Teachers have the weight of the world on their shoulders and it’s all too natural to feel pulled down by obligation, or even failure. But, your best learning opportunities are almost always when you take a risk with something new or relinquish control to your students and watch what they can do with it.

So, go easy on yourself when things don’t exactly go according to plan. And don’t worry, that missed dropshot is just the first point.

- Take your time

The best players don’t rush through their serves. They have a rhythmic routine (four bounces or jumping from side to side) and they take their time winding up for the perfect ball.

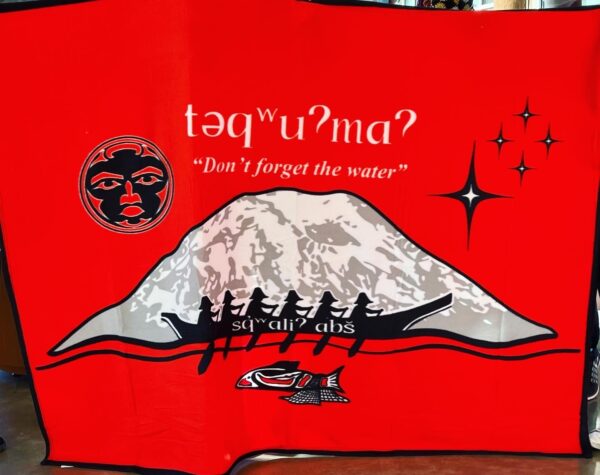

Our equity team often discusses how educators tend to operate on “white guy time.” Or, more formally, it’s the “sense of urgency” found in white supremacy culture. For example, our work with the Nisqually tribe around our Thunderbird mascot is still in process since I wrote that piece in December. Faster isn’t always better.

Sure, sometimes lesson ideas come from the drive to work, but more often, you build units based on evidence of student learning and interest. There’s a reason 44% of teachers leave the profession within five years (and that was pre-pandemic!). It takes patience and persistent, thoughtful, reflective effort to stay in the game.

- If it’s not fun, it’s not worth it

This is perhaps the most important reminder I’ve gained this season. I ruined tennis for myself in high school by putting too much pressure on myself. Seriously, I didn’t play for ten years because I felt like I had to be the best or not play at all.

It’s been my number one goal as a coach to help our girls not fall into that trap.

If anything in life is more stress than payoff, it warrants some serious reconsideration or a mindset shift at the very least.

Many of my classroom procedures are in place to save myself a headache. For example, I’m flexible on due dates because I don’t want to arbitrarily punish students, but also because I don’t want that anxious feeling when 10 final essays are missing by the due date. I’m in education for the long haul and if I wind myself so tight that I’m constantly stressed, then it isn’t worth it.

This is a tough lesson to give to educators right now as 55% of teachers are seriously thinking of leaving the profession. And, I don’t blame them. Several of my teacher friends have left with very valid reasons for doing so.

Obviously, teaching is a job (something I think we forget as it’s so often labeled a “calling”) and it is therefore not going to be “fun” all the time.

Our girls compete and obviously want to win matches, but tennis is first and foremost a game. It should be fun. Practices where they’re commentating for each other’s points in British accents are pure gold.

***

So, as we wrap up the school year, the third tainted by the pandemic, I hope some of these reminders help you refocus and practice some self care. Remember, you can’t win ‘em all, go easy on yourself, take your time, and have fun!