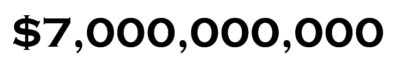

According to a report on The Huffington Post, the money spent on the federal School Improvement Grants (SIG) didn’t accomplish anything. That’s $7 billion dollars spent on failed efforts. The final report from the Mathematica Policy Associates said the “SIG grants made essentially no difference in the achievement of the students in schools that received them.”

SIG grants offered low-achieving schools just four choices:

- close the school

- convert the school to a charter school

- replace the principal and half the staff

- or replace the principal, use achievement growth to evaluate teachers, use data to inform instruction, and lengthen the school day or year.

Wow, those sound like popular choices being floated right about now, don’t they? How many legislators at the state and federal level like the idea of converting public schools to charter schools? Or maybe they think replacing staff or using achievement growth to evaluate teachers or using data to inform instruction or lengthening the school day or year—or some combination of the above—is the magic bullet to cure the ills of schools in America.

But none of those solutions worked.

None of them improved student achievement.

Of course, not one of the four choices has a strong research base to support using it. There is no compelling reason, based on actual science or statistical study, to choose any one of them.

So all that money went down the drain.

(It makes my stomach hurt just to think about all that wasted money. What we could have done with $7 billion dollars!)

Now for the good news.

There are, in fact, four whole-school reform models that the Department of Education has approved as being evidenced-based:

- Success for All

- The Institute For Student Achievement’s (ISA)

- The Positive Action System

- Small Schools of Choice (SSC)

The fourth model, by the way, is the only one that is not proprietary. Small Schools of Choice are organized around smaller units of adults and children. Three core principles provide the framework: “academic rigor, personalized relationships, and relevance to the world of work.” As I looked over the SSC plan I noticed items like thematic units, longer instructional blocks, common planning time, adults acting as advisers to 10-15 students, partnerships with the community and parents. Those are all good things that we KNOW work.

Now for the really good news!

The Center for Research and Reform in Education at Johns Hopkins University has a brand new website called Evidence for ESSA. Their staff has reviewed every math and reading program for grades K to 12 to determine which meet the strong, moderate, or promising levels of evidence defined in the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). As they say, “It’s long been said that education needs its own version of Consumer Reports—authoritative, well researched, and incredibly easy to use and interpret. We hope Evidence for ESSA will be just that.”

- A program is ranked strong if it has a significant positive effect with at least one randomized study.

- A program is ranked moderate if it has a significant positive effect with at least one study that is classified as “quasi-experimental”—a matched study, say.

- A program is ranked promising if it has a significant positive effect but the study was classified as “correlational.”

Notice that even for moderate and promising programs, the effects are still good—the program shows a significant positive effect. The reason those programs get a lower rating isn’t that they have poorer results. It’s because the controls of the studies were not as rigorous.

Ah, reading these standards take me back to my MA class on statistics. (Which I passed by the skin of my teeth.)

As soon as I found out about the CRRE site, I sent the information to my district administrator in charge of curriculum. He says this site will be very useful.

No kidding.

There’s not an endless amount of money to spend on education. We all know that. Let’s spend it where we know it will work.

, facing the class and modeling the correct movements in reverse, monitored and corrected each student’s letter formation. Children across the country all learned the same method of writing, they all had handwriting that was similar—and their handwriting was legible.

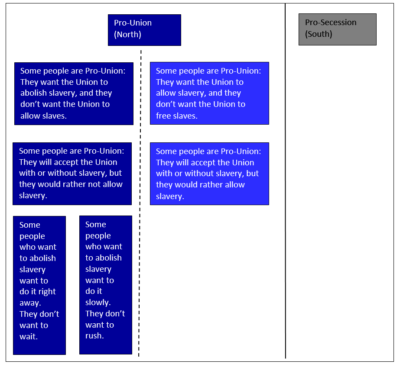

, facing the class and modeling the correct movements in reverse, monitored and corrected each student’s letter formation. Children across the country all learned the same method of writing, they all had handwriting that was similar—and their handwriting was legible. But Lincoln didn’t stop there. He went on. “It is easy to conceive that all these shades of opinion, and even more, may be sincerely entertained by honest and truthful men.”

But Lincoln didn’t stop there. He went on. “It is easy to conceive that all these shades of opinion, and even more, may be sincerely entertained by honest and truthful men.” priate for their level in every subject, just like any other special needs group. They require teachers who are trained to meet not only their academic but their unique social and emotional needs. And their number one need must be met on a regular basis—quality time with their intellectual peers.

priate for their level in every subject, just like any other special needs group. They require teachers who are trained to meet not only their academic but their unique social and emotional needs. And their number one need must be met on a regular basis—quality time with their intellectual peers.

oy was still crushed. He had every reason to be. He had toiled long and hard cutting all the PVC pipe pieces for the original design—and for a small kid, it was laborious work. Clearly, he felt like all his effort was for nothing.

oy was still crushed. He had every reason to be. He had toiled long and hard cutting all the PVC pipe pieces for the original design—and for a small kid, it was laborious work. Clearly, he felt like all his effort was for nothing.