Early in May, the Washington Teacher Advisory Council hosted a conference with the title Vision and Voice: The Future Is Now. Award-winning educators from all over the state gathered to share ideas and learn from one another. The conference was packed with high-powered teacher leaders that I admire- educators with blogs I love, whose podcasts I listen to, whose advice I have taken, and whose encouragement has bolstered me. We even kicked off our first evening with a keynote from the newly minted National Teacher of the Year, Mandy Manning. What an amazing experience to be among my educator heroes!

As I reflect on that event, I am so grateful to all of the amazing teacher leaders I have encountered over my career, and I know that their impact on my own practice has been immeasurable. I never fail to be inspired. I always learn. I return to my classroom reinvigorated and ready to shine my own light.

I teach English, so I my love of figurative language should come as no surprise. When I think of “light” as a metaphor for learning– from the proverbial “light bulb” moment to “lighting a fire,” these images work for me. As an educator, I’m all about creating light, spreading it, and feeling its warmth.

But there can be more to it than just bringing your light to your classroom and sharing it with your students. If you have talents to share, if you can inspire others, then you may see it as your responsibility to become a teacher leader. You’ve heard the phrase, “Don’t hide your light under a bushel,” right? We have the responsibility to give back to our colleagues, our communities and our profession whenever we are able.

That phrase about the bushel sticks with me. So often, as a professional, as a woman, as a child of poverty, I was in situations in which I was expected to know my place, to stay quiet, to comply and fade into the background. Something inside me has always rebelled at this, some idea that I can do more good for others if I stop dwelling on my own insecurities or a twisted sense of modesty or humility. (See Imposter Syndrome Ted Talk)

In a letter to her younger self, Hilary Clinton tells how her sixth grade teacher told her not to hide her light under a bushel basket. She passes this advice on to other young girls in this Teen Vogue article.

So what is this “bushel basket” all about? It’s from the New Testament. In the King James version Matthew 5:15 says, “Neither do men light a candle, and put it under a bushel, but on a candlestick; and it giveth light unto all that are in the house.” Now, historically, a bushel was a container for goods, such as grain, that became a unit of measure. So this is a bit weird in modern terms. But you get the idea. In this context, the light could be your faith, but it can also be your wisdom, your learning, your spark. Why hide a light?

So what is this “bushel basket” all about? It’s from the New Testament. In the King James version Matthew 5:15 says, “Neither do men light a candle, and put it under a bushel, but on a candlestick; and it giveth light unto all that are in the house.” Now, historically, a bushel was a container for goods, such as grain, that became a unit of measure. So this is a bit weird in modern terms. But you get the idea. In this context, the light could be your faith, but it can also be your wisdom, your learning, your spark. Why hide a light?

Beyond that, if you have it, share it. An old Italian proverb says, “A candle loses nothing by lighting another candle.” We educators know that sharing our wisdom, our learning and our knowledge is the greatest gift we have to give. When it is needed, we must be ready to share. And we lose nothing in the sharing of it.

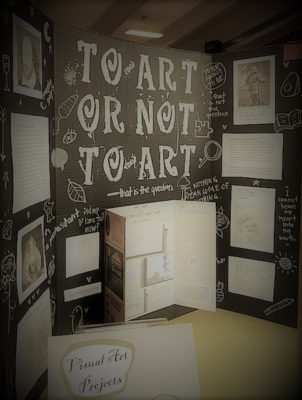

It’s relatively easy to go to our individual classrooms and share our knowledge. Teacher leaders take it a step further: staff trainings, mentoring, coaching, conference presentations, blogging, etc. That light that such teachers share grows exponentially.

We all have different talents, viewpoints, strategies and solutions to share. There are many paths to leadership, as varied as the individuals themselves. Some lead by supporting their colleagues on a day-to-day basis. Others take their show on the road, spreading their light leading professional development or giving keynote speeches. Some blog or participate in chats on Twitter. Some take a path that leads them out of the classroom and into administration, but, as long as their hearts are still in the classroom, they lead as teachers.

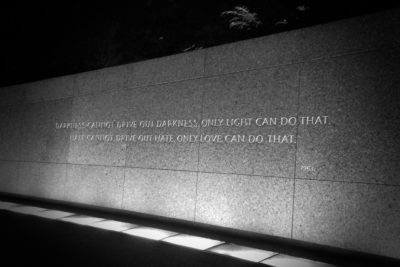

Now let me take this a step further. Where there is light, there is darkness. And let’s face it; there have been some dark moments in our schools recently. There are dark issues faced by our students and our colleagues. To fight the darkness, we need to rally behind the light. We teachers can do so much to help our students as they face the future, as they become the problem-solvers of tomorrow. As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., famously said, “Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.” (from his “Love Your Enemies” speech)

Now let me take this a step further. Where there is light, there is darkness. And let’s face it; there have been some dark moments in our schools recently. There are dark issues faced by our students and our colleagues. To fight the darkness, we need to rally behind the light. We teachers can do so much to help our students as they face the future, as they become the problem-solvers of tomorrow. As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., famously said, “Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.” (from his “Love Your Enemies” speech)

Don’t we have a responsibility to lead? To lead our students, and perhaps also our colleagues and communities? Find your way to bring the light. As Oprah Winfrey says, “You have to find what sparks a light in you so that you, in your own way, can illuminate the world.” (from the finale show)

As for me, I’m all in on this light metaphor. I’m going to let my light shine, and, furthermore, “I am on until I am dead, like a light bulb,” as Henry Rollins once said. (from Henry Rollins: Still Angry After All These Years, LA Weekly)

So, get out there and shine, my teacher leader friends. You are needed now more than ever to strengthen our profession and guide our students through troubling times.

Remember:

“Nothing can dim the light which shines from within.” – Maya Angelou

I’m currently struggling with such a dilemma. Our district is strenghtening its retention policy to discourage a rapid uptick in junior high students with failing grades. The majority of district staff believe that if our policy has more “teeth,” if we actually retain more students, then others will work harder. This issue strikes a very harsh chord with me, and it’s personal.

I’m currently struggling with such a dilemma. Our district is strenghtening its retention policy to discourage a rapid uptick in junior high students with failing grades. The majority of district staff believe that if our policy has more “teeth,” if we actually retain more students, then others will work harder. This issue strikes a very harsh chord with me, and it’s personal.