All teachers get good, over time, at being resourceful. We learn to scavenge for what we need to do our jobs. We get comfortable with discomfort, with working with less-than-optimal environments (in some particularly bad cases, “less-than-optimal” would be a laughable understatement). This is not limited to any particular state – from what I’ve read lately, and what I’ve experienced teaching in different states (NY and WA), this is a nationwide public school reality.

A spotlight has been directed on our lack of investment in school buildings, equipment, and furniture. As teachers in West Virginia, Oklahoma, Arizona were striking in the beginning of this year, a wave was building: educators around the country have been sharing about ways that school buildings are failing kids and failing teachers. We saw Baltimore students huddled in coats and mittens in their freezing classrooms, a story that originated with a tweet by NFL player-turned teacher Aaron Maybin. This attention led to a GoFundMe campaign that raised more than $84K for space heaters and outwear for Baltimore students – obviously not a long-term fix, but evidence of public support for better classroom conditions.

Personally, I’ve taught in classrooms with broken furniture, no whiteboard, no projector (in a visual arts class!), broken floor and ceiling tiles, leaking ceilings, and above-80-degree or below-60-degree temperatures. One school had a staff of 40+ that shared a single, one-toilet bathroom, while 300 students shared 2 bathrooms of 3 toilets/each (and plumbing problems were frequent).

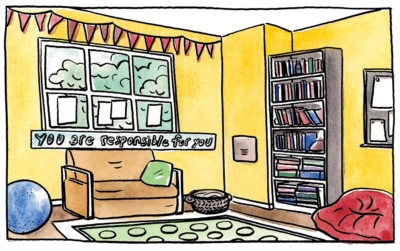

I have dragged a stained, fraying area rug from a school trash pile and dyed it with I fabric dyes that I found in an old cupboard – it was my “circle time” rug for 2 years. I have pushed students in wheelchairs over tangles of extension cords and directed electric fans at students looking particularly overheated. I’m active in my local Buy Nothing facebook group, where neighbors share items they’re giving away – I’ve gotten art materials and classroom furniture that way. My assistant principal found a pair of computer speakers at Goodwill for me.

But I am so commonplace in this – every educator does this, often more, to try and meet students’ needs. I have seen special ed teachers and paraeducators, in particular, go to unimaginable lengths to make classrooms and environments safe and accessible for students with disabilities.

Rachel Cohen of the Washington Post points out that this is a long-standing problem of Federal vs. State, as far as infrastructure investment. “U.S. school buildings are 45 years old on average. But these problems disproportionately affect poor communities. In older cities, particularly industrial ones, schools average closer to 60 to 70 years old.”

Cohen brings up an idea put forward by Mary Filardo, the director of the 21st Century School Fund, “suggest(ing) school districts should…be able to leverage up to 10 percent of their Title I funds for capital expenses — currently, the federal money distributed to high-poverty districts can go only toward operating costs.”

While I don’t like that this would mean less funding – vital, in my experience – for operating costs, I do agree that the cost of infrastructure improvements in schools should be shared between Federal and State governments.

Locally, Seattle is putting levy funds – special election-based tax funds – towards improving Seattle Public Schools facilities. In 2016, the Buildings, Technology, and Academics IV Capitol Levy (BTA IV) passed by 72% of the vote, allocating $475.3 million toward school building construction, to be received and used between 2017-2022. Three existing buildings will be re-opened after improvements/updates to address growth in SPS enrollment. In a district as large as SPS, it can be hard to reconcile the good news of this kind, with the reality of so many day-to-day inadequacies in our classrooms and school buildings.

In an environment of scarcity, it’s also hard not to resent the newer buildings in the district, even while I know that the funds can’t go everywhere all at once. The most we can do is to be patient, and to advocate for more funding (locally, as well as state and federal), particularly for schools serving students living in poverty and students with diverse access and safety needs from their learning environments. Last year (in my old school), a group of Microsoft workers toured our building. They remarked on things that we had long since stopped seeing: water damage on the walls, cones around playground drains that don’t drain, exposed holes in acoustic-tile ceilings. It reminded me that sometimes my acquired skills in “making do” go too far – we can get used to unacceptable environments when we lose hope that change will happen.

While I try to raise my expectations of my classroom and school building, I’ll continue to scavenge and be resourceful. In my hunt for district and regional policy information regarding school facilities, I also came across this: guidelines for safety in art classrooms! It’s a good learning resource and a reminder that an optimal academic environment requires a safe and accessible space for everyone, and I can start with my own room.