Last week the ACLU sued the OSPI because Washington students with emotional disabilities are suspended or expelled from school at twice the normal rate. The suit alleges that the state should ensure that teachers “de-escalate” situations in which students with emotional disorders are having outbursts.

I have always admired the ACLU. They consistently take contrarian stands in support of the most marginalized people in our society. It’s an important role, now more than ever.

And on this issue they are true to form, advocating for the highest of the high-needs students, the kids with disabilities that prevent them from controlling their behavior well enough to make it through a day in school without having a verbal or physical meltdown or endangering their classmates or teachers. These kids need advocates.

I know because I’ve got one of these kids in my class this year. He has an IEP for academics and behavior. He performs about two grade levels below his peers and spends most of the school day in a series of learning support small-groups.

And as long as no one makes any demands on him, he’s fine.

But it’s hard to go through a school day without anyone putting demands on you. Teachers are supposed to ask students to do such things as read, write, solve math problems, join discussions, walk in the hallway, stop talking, take turns, and so on. And when someone asks this guy to do any of those things, there will be an outburst. There will be yelling, door-slamming, chair-throwing, running off and swearing. And by swearing, I mean serious filth; the kind of talk you’d expect from a hung-over stevedore trying to start a cold, 2-stroke outboard engine.

And then there’s the playground. Most kids are able to handle the give-and-take of the somewhat unstructured playground environment. There’s bound to be some teasing, perhaps some taunting and occasionally it can get a little nasty, which is why we have supervision. Most kids know when to pull back before a situation turns violent, but once in awhile we have kids who don’t, and again that’s why we have supervision.

This little guy has no filter, no control. The slightest slight by another student is cause for a full-on response, consisting of violence, racial and sexual insults and, of course, swearing.

All of this is despite the fact that he has a full-time, one-on-one aid. She shows up every morning, follows him around all day, helps him with his assignments and does everything possible to de-escalate his outbursts. It’s literally a full-time job and it’s required by his IEP.

Which brings me back to the ACLU lawsuit.

I get it; kids should not be suspended or expelled because of their disability. But as I explained to the parents of this particular student, there comes a time when I have to advocate for the rest of the class. And the rest of the class is terrified of this student. When he enters the room, they all get quiet and try to become as small as possible. His racial insults make them cry. He’s getting big enough that when he hits them it causes serious pain.

Consequently, he has been suspended at least three times this year. We did not do it lightly. We were fully aware of the consequences of our actions. We knew that he suffers a disability that affects his ability to self-govern.

But there are 600 students in our school and 27 students in my class. They need advocacy, too. At some point the right thing to do for the larger population might not be the right action for one particular person. When a student, no matter who it is, crosses the line and does or says something completely beyond the pale, suspension is an action a school must have at its disposal.

I’ll be interested to see how this lawsuit proceeds. If there’s another way to deal with students who display extreme behavioral disorders, I’d love to know about it. But until then, I think we need to continue to use school suspension as a last resort.

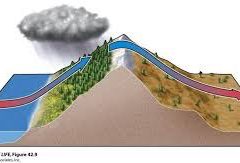

There’s a place on the Washington coast called Taholah. I’ve been there a few times on my bicycle, riding up Highway 109 from Ocean Shores. The scenery is staggering. There’s huge trees everywhere, a river on the north end of town and an ocean to the west.

There’s a place on the Washington coast called Taholah. I’ve been there a few times on my bicycle, riding up Highway 109 from Ocean Shores. The scenery is staggering. There’s huge trees everywhere, a river on the north end of town and an ocean to the west.

If your school is anything like mine, you’re about to enter Testing Season. We come back from Spring Break, get reorganized and start gearing up for the SBAs. We review important material and have our students take practice tests on their computers. We teach test-taking strategies and emphasize the importance of sleep, diet and attendance.

If your school is anything like mine, you’re about to enter Testing Season. We come back from Spring Break, get reorganized and start gearing up for the SBAs. We review important material and have our students take practice tests on their computers. We teach test-taking strategies and emphasize the importance of sleep, diet and attendance. After our new Education Secretary, Betsy DeVos, stepped into a public school last week, perhaps for the first time, she told a journalist that the teachers seemed to be “waiting to be told what they have to do.”

After our new Education Secretary, Betsy DeVos, stepped into a public school last week, perhaps for the first time, she told a journalist that the teachers seemed to be “waiting to be told what they have to do.” I’m getting a new student tomorrow. I haven’t met him yet, but I’ve met his discipline record, and it’s staggering. He’s packed more misbehavior into his short life than most of us commit in a lifetime. Not only that, but academically he’s at least three years below the rest of my class.

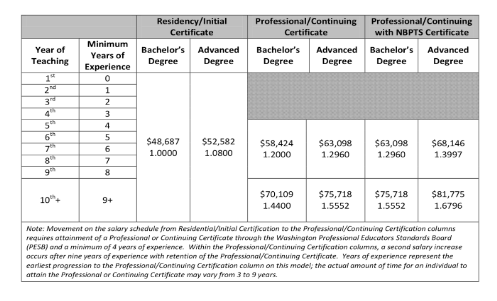

I’m getting a new student tomorrow. I haven’t met him yet, but I’ve met his discipline record, and it’s staggering. He’s packed more misbehavior into his short life than most of us commit in a lifetime. Not only that, but academically he’s at least three years below the rest of my class. Last month we had an incredible event. Nearly 100 NBCTs met to talk about how to preserve the National Board bonus in Washington State. My role was interesting; I got to monitor the conversations at seven different tables and glean the common, high-leverage ideas that emerged. What I learned was this:

Last month we had an incredible event. Nearly 100 NBCTs met to talk about how to preserve the National Board bonus in Washington State. My role was interesting; I got to monitor the conversations at seven different tables and glean the common, high-leverage ideas that emerged. What I learned was this: I had plans for last Wednesday.

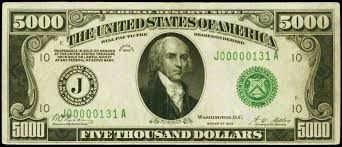

I had plans for last Wednesday. I’ve been on more committees, task forces and planning teams than I care to remember. Many of them were productive and well worth my time. One particular team produced

I’ve been on more committees, task forces and planning teams than I care to remember. Many of them were productive and well worth my time. One particular team produced

Every National Board Certified Teacher has a story. This is mine.

Every National Board Certified Teacher has a story. This is mine.