The House We’ve Inherited

I am an unapologetic book nerd. Perhaps this is not a surprising trait for an English teacher, but lately, I find myself diving into nonfiction with the same fervor as I would a captivating novel. It just seems there is always more to learn (and unlearn) and my reading list is infinitely growing.

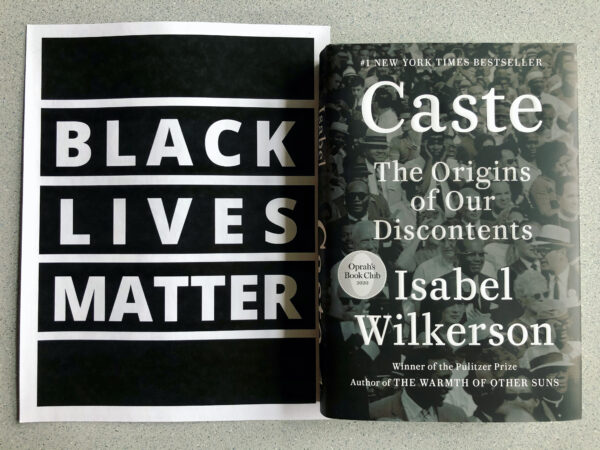

This past month, I had the opportunity to spend four weeks facilitating a small group discussion as a part of CSTP’s WERD book study of Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents by Isabel Wilkerson. I can honestly say that reading this book has forever changed how I view our country’s past, present, and future.

I know I can’t do this incredible book justice, so I won’t even attempt a poor summary here. Instead, I just strongly encourage everyone to read it. Especially educators. The caste system that Wilkerson lays out as the foundational framework of our nation has dire implications for every facet of our systems, including education.

Wilkerson has numerous apt metaphors for caste, but her analogy of America as an inherited old house particularly resonates with me. While it may seem beautiful from the outside, it has deep structural issues worn from generations and it’s maintenance can’t be ignored.

She writes, “Not one of us was here when this house was built. Our immediate ancestors may have had nothing to do with it, but here we are, the current occupants of a property with stress cracks and bowed walls and fissures built up around the foundation. We are the heirs to whatever is right or wrong with it. We did not erect the uneven pillars or joists, but they are ours to deal with now. And, any further deterioration is, in fact, our hands” (Wilkerson 16).

I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard arguments such as “my grandparents didn’t own slaves” or “I’m not a racist, I love all my students,” which both are branches of the same tree. They work to distance the speaker from any accountability, and move them past uncomfortable feelings of shame toward more palatable places of ignorance and inaction.

The Schoolhouse

Just looking at our schools, (though it’s impossible to discuss education without also analyzing the systems around and within) Wilkerson’s house metaphor shines a light on the innumerable inequities built into education.

In our educational “house,” student mental health and increasing teacher workload are the stress cracks. The bowed walls are standardized tests, curriculum mandates, and graduation requirements. Foundation fissures are inequitable academic tracking, access to college level courses, and disproportionality in discipline data.

All of these issues come from flaws in the original design, but they are now up to the current practitioners and leaders to fix.

I wasn’t around for the opening of the first Native American boarding school on the Yakima Reservation. My grandparents didn’t rule on Brown v. Board of education. I was still just in high school when the Common Core State Standards were first established.

I can’t be “blamed” for any of the above, just like “it’s not my fault” I’m white, which is why shame and blame are unproductive.

Instead, I believe that, as Wilkerson says, “the price of privilege is the moral duty to act when one sees another person treated unfairly (386).

So, if I stand for public education and the innate potential in all students, it seems imperative that I do whatever is in my power to help fix our systems to best serve them. And, as I work to learn and understand my white privilege, I can and will blame myself if I choose to remain ignorant and stay silent.

What’s Next?

In our four Caste meetings, my group rarely had time to discuss all the questions because we were too busy reaching deeper, truly listening, and engaging with one another. We created a space to be vulnerable and share our thoughts about the books, our classrooms, our families, and the very real fears we have about the state of our country.

Wilkerson writes, “The owner of an old house knows that whatever you are ignoring will never go away. Whatever is lurking will fester whether you choose to look or not. Ignorance is no protection from the consequences of inaction (15).”

My experience discussing the painful truths of our nation with other educators was invaluable. In joining the book study, we chose knowledge and action over complacency.

Many questions had seemingly unreachable answers. “What role can we play in our schools and society to dismantle racism and caste?” and “What will it take to dismantle the American caste system?”

But we know that real, lasting, systemic change comes from the grappling, unlearning, and exchange of ideas that bends MLK’s moral arc of the universe towards justice.

I took the ideas I learned in this book club into our district equity advisory committee. I shared powerful quotes with my student teacher to spark discussion on her social justice teaching journey. I had discussions with my friends and family about much of what I learned from Wilkerson and my fellow educators.

These are small, but important steps around difficult conversations. Because, while many educators across Washington chose to read a 388 page book on the history of systemic casteism, there are many more who tune out any professional development related to equity.

Next, I wonder how we can make the kind of conversations we had in book study the new normal? How do we make unearthing difficult truths about our past an integral part of shaping our future?

Works Cited (Because I always do the assignments I give my students…)

Wilkerson, Isabel. Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents. New York, Random House, 2020.

Pingback: No, Slavery Was Not “Involuntary Relocation” - news page

Pingback: No, Slavery Was Not “Involuntary Relocation” - News 4 Buzz

Pingback: Constructing Equitable Schools: One Block at a Time | Stories From School

This book moved me – over and over again. It is a must read for anyone on the journey to do the work of anti-racism. I followed it with The Sum of Us by Heather McGhee and found them to be a good pairing.

I see where you’re coming from. My family immigrated to the U.S. in 1999. We were at a disadvantage compared to people who lived in the U.S., people whose parents and grandparents and great-grandparents were born and raised here.

Our culture was different. Our understanding of a how a country worked was different. My parents were raised in communist/socialist Ukraine, where breadlines were the norm and there was a constant shortage of basic necessities. They grew up in a culture with a survival mentality. Both of them had parents and grandparents who were killed or imprisoned unjustly by the communist regime. My dad’s grandfather was shot to death by communist soldiers in his own front yard, because they were trying to requisition his cow for the communist party. He was hard of hearing so did not understand what was happening and tried to stop them.

You can only imagine the culture shock my parents and I went through when we walked into a grocery store and saw the shelves full of food. I think for immigrants equity in education begins with a meeting with school administration, where the American school system is explained. It begins with them understanding their rights. You can’t just assume that how things are here in the U.S. extends to the rest of the world. That’s ignorance.