Sometimes, you don’t realize how much you need a hug until someone reaches over and gives you one. Sometimes, you forget to hug the people closest to you and say “thank you.” Anyone who became an educator knows this is part of the deal. We don’t become teachers or counselors for the praise. We do it because we believe in community and the power of education to change lives. We believe our work makes the world a better place.

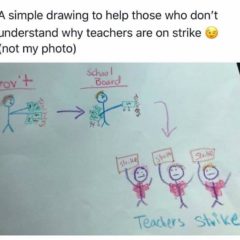

But for many public school educators this summer has presented a challenge to the “Why” of our work. By now, you’ve seen or read the news about education association contract negotiations. When the legislators finally agreed to put money towards funding the McCleary decision last spring, districts across the state celebrated. They also began to grapple with what the new funding would mean in terms of teacher salaries and program development. Simultaneously, education associations across the state began re-negotiating their contracts, specifically focusing on compensation. The purpose of this post isn’t to explain the ins-and-outs of the work (start here if you’re feeling wonky and listen to Nerd Farmer & Citizen Tacoma) but what I am going to ask you is to support the educators in your community.

We may disagree on the way McCleary funds should be spent locally or what percentage should go to educator pay. Perhaps you feel the whole thing is such a confusing mess. Regardless, it’s critical that you support your public school staff.

I’m part of Tacoma Education Association and we’re headed into day three of striking. Every box of donuts, case of bottled water, tray of cookies, baggie of fresh fruit, or cup of coffee dropped off to striking educators, is like a giant hug of support that means more than any pictures, hashtag, or blog post could convey.

As I reflect on the last few days and look through the countless photos of educators from across this state, I’m reminded of a couple things. Teachers aren’t perfect. We have our faults. We mess up. But because research shows that an effective classroom teacher is the number one in-school factor impacting student achievement, we have to make sure that the best teachers are working in our public schools. A competitive compensation package is one way to ensure this.

If that doesn’t persuade you, then think about the individuals. The person in the red shirt holding a sign is the same person who taught your son to read last year. The lady in the capris is the same person who comforts your child when he falls down on the playground. We are the people who wipe snotty noses, help tie shoes, celebrate SAT scores, wrestle through career choices, and cheer your baby on from kindergarten to senior year.

Support your educators any way you can.