11/6/2019 EDIT: See the comments for some updated information since the post originally published. –mg

Last spring, the state legislature made a policy move that, in the Tweet-length-version, seemed like a win for kids often marginalized in our system. The oft repeated phrase? “Legislators delink state tests from high school graduation.”

The essential premise as I understand it: The current assessment system (SBA) didn’t deserve greater weight than the rest of a student’s academic performance when it came time to determine if the student had earned their diploma.

Ultimately, this premise prevailed, and the resulting policy established eight separate pathways toward earning a high school diploma. So far, so good. I’m on board.

Unfortunately though, as I’ve tried to sort out what this means for my current students, I can’t help but be concerned. Unless I’m missing something big, there still will be a handful of kids… particularly in the graduating class of 2020… for whom no pathway to graduation exists.

Continue reading

As an educator in a rural district, I have spent many years observing how our students often have less access to the options that are readily available in larger and urban districts. For instance, in addition to fewer electives, we offer few opportunities for students to take AP or dual credit courses, forcing many of our best scholars to travel forty miles to a community college as Running Start students. Additionally, where other districts had classes to support students who failed the state assessments in math or language arts, we did not have the resources or staff to offer such dedicated courses. Instead, because we are committed to our kids, our staff has worked outside of the regular schedule to support them and create Collections of Evidence or prep for test retakes.

As an educator in a rural district, I have spent many years observing how our students often have less access to the options that are readily available in larger and urban districts. For instance, in addition to fewer electives, we offer few opportunities for students to take AP or dual credit courses, forcing many of our best scholars to travel forty miles to a community college as Running Start students. Additionally, where other districts had classes to support students who failed the state assessments in math or language arts, we did not have the resources or staff to offer such dedicated courses. Instead, because we are committed to our kids, our staff has worked outside of the regular schedule to support them and create Collections of Evidence or prep for test retakes. On May 9th, Governor Inslee signed a

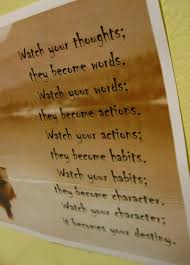

On May 9th, Governor Inslee signed a  It takes a little knowledge to dig a little deeper sometimes. This month, I am hitting the knowledge. Next month – I am digging a little deeper. What am I talking about? Character education! Let’s first get a little history…

It takes a little knowledge to dig a little deeper sometimes. This month, I am hitting the knowledge. Next month – I am digging a little deeper. What am I talking about? Character education! Let’s first get a little history…