This is the first of a series of posts I will be writing regarding the current Teacher and Principal Evaluation System (TPEP) in Washington State. Each post will examine findings from the University of Washington’s Final Report on TPEP, titled ‘Washington’s Teacher and Principal Evaluation System: Examining the Implementation of a Complex System.’ The full report can be found here: http://www.education.uw.edu/ctp/sites/default/files/UW_TPEP_Rpt_2017_Rvsd_ADA.pdf

Washington’s Teacher and Principal Evaluation System (TPEP) created fundamental changes to the way teachers and principals talk about teaching and learning. Moreover, TPEP established a shift in how teachers are evaluated and how they evidence their achievement in eight criteria. The system requires that each teacher complete a comprehensive evaluation (all eight criteria, including measurements of student growth towards specific learning goals) once every four years and a focused evaluation during the other three years (evidencing one criterion and one student growth goal). A new teacher must successfully complete the comprehensive evaluation for three consecutive years before he/she can move towards a focused evaluation. Additional legislation now allows a teacher to carry his/her comprehensive summative rating into the focused cycle as a way to promote growth and zero in on a focused area of weakness for improvement without fear of receiving a worse summative evaluation rating at the end of the year (see WAC: 392-191A-190).

I was an early adopter of TPEP. As a building leader and local education association president I felt it was important to see what this new process looked like first hand so I offered myself up as a guinea pig. Thankfully, a few of my building colleagues did the same. Four and a half years ago we underwent the comprehensive system for the first time and like anything new, we (both teachers, building, and district admin) muddled through the process, putting this new policy into practice. We learned a great deal from trial and error. Within a few months our building established an effective system based on routine meetings (every three weeks) and grounded in teacher agency over artifacts. Our process is now streamlined in contract language and having completed a full cycle (1 year of comprehensive and 3 years of focused) I can confidently say that conversations about teaching and learning are firmly entrenched in language found in the criteria. We’ve established a process that helps teachers and administrators talk about our work with shared values and a common language. A recently released report from the University of Washington regarding the implementation of TPEP echoes similar sentiment from stakeholders in districts around the state (Elfers and Plecki, xii).

I’m back on the comprehensive model this year and finding the process to be inhibiting to my growth as a teacher. It’s not that I’m unwilling to closely analyze my practice to demonstrate my achievement in these areas. In fact I welcome these opportunities. But evidencing eight criterion (three pieces of evidence for each) and two student growth goals (with three different assessments) is challenging to do well in one academic school year. To be fair, I live this work every day. Half of my day is spent serving as an instructional coach supporting our building teaching staff as they prepare for meetings and reflect upon their practice. The University of Washington TPEP report indicates that the comprehensive evaluation model within a single year poses series concerns for teachers, school administrators, and superintendents. “More than three-quarters of teachers, four-fifths of school administrators, and 71% of superintendents either strongly or somewhat agreed that the comprehensive evaluation attempts to cover too many aspects of teaching in a single year.” (Elfers and Plecki, xiii). But now that I’m back in the mix of the twenty four pieces of evidence, six assessments, etc… I’m feeling like I can’t juggle all of these criteria well and as a result, I’m not demonstrating my best work and that has me concerned. These feelings signal to me that I’m treating the comprehensive evaluation system as a checklist of attributes and indicators that I have to reach so that I can show that I am a “Distinguished” educator this year so that next year I can go back into the focused model and take some real risks, pushing myself in my areas of weakness so that I can make substantive changes without fear of losing my “Distinguished” label. I’m tired of proving that I’m “Distinguished’ enough to do this work. I’m a National Board Certified Teacher, once renewed, who has shown through a variety of means that I continually seek out opportunities to grow professionally so that I may be a better teacher for my students. The comprehensive evaluation system makes me feel weighed down and less reflective, not more.

What about our newest teachers? Our state, like others, is struggling to retain teachers in the profession, yet we immerse them in this complex process right out of the gate. 84% of building administrators felt that covering all aspects of the comprehensive evaluation with a first year teacher was of major or moderate concern (Elfers and Plecki, xiii). So how can we expect new teachers to the profession to carefully and thoughtfully engage with this instructional evaluation tool? Spoiler alert: I’ll address the rise in support systems that have emerged since the implementation of TPEP in my next related blog post. Nonetheless, the UW report on TPEP Implementation doesn’t zero in on the experience of new teachers (from the perspective of the new teacher) as an analyzed sub group, but there are hints at the familiarity of new teachers with TPEP. The report finds that teachers who recently graduated from a teacher prep program (within the past three years) largely had experience with TPEP related criteria such as use of assessments to inform instructional practice and the assessment and collection of evidence of student growth (Elfers and Plecki, xii, 6). But does experience alone mitigate the challenges presented in the first year of teaching coupled with the use of a comprehensive evaluation? I’m hoping to see additional research in this area. So I wonder, what would happen if new teachers began with focused area, allowing for richer reflection and analysis in one area, instead of jumping head first into the all eight criteria? This would create less pressure and more confidence for those just starting into the career.

So where do we go from here? We’re now almost five years into implementation and perhaps now is the time for policymakers to step back and make adjustments to this system. Re-examining how we evaluate our newest teachers and ensuring that all teachers are able to take risks, improve weaknesses, and cultivate practice will create an even stronger, perhaps more sustainable teaching force for our students.

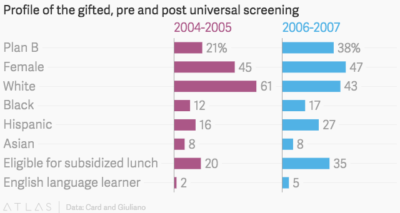

Universal screening eliminates the reliance on nominations/referrals (which eliminates any potential of bias or problems of access skewing the identification process).

Universal screening eliminates the reliance on nominations/referrals (which eliminates any potential of bias or problems of access skewing the identification process).