It is a classic “damned if you do, damned if you don’t.”

My own three children are in three different buildings in the same school district (one elementary school, one middle school, one high school; all in a different district from where I work). Technically, their teachers have been directed by district admin not to send homework yet.

My elementary schooler’s teacher has done so anyway, with the clear communication that it is optional. She has sent suggested math pages from the workbook, along with video guides. She has also video recorded herself reading aloud to kids. My son is in a Spanish-immersion program, so he is also charged with continuing his online practice program. I’m okay with all of this.

My middle school son was asked by his science teacher to finish up a project about natural disasters that they started before the shutdown. His math teacher has sent e-packets of worksheets. There hasn’t been a clear statement of “optionality” for these. We haven’t heard from his other teachers. I’m okay with all of this.

My high schooler? Radio silence from teachers. I’m okay this, too.

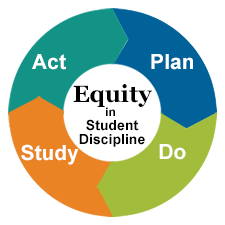

Seattle Public Schools Superintendent Denise Juneau has stated that the largest school district in Washington will not transition to online learning in the immediate future. Meanwhile, the Los Angeles (LAUSD) school system is investing $100 million in making sure kids without online access are provided tech and internet during the shutdown. From one side, Superintendent Juneau is being praised for her pragmatic view of the access divide among Seattle students. The other side is quick to drag her publicly. (I’m not hiding my bias well, am I?)

Continue reading