This blog is brought to you by boxes of Christmas decorations, a beleaguered faux Canadian Pine, and the heavenly aroma of black-eyed peas and pork.

New Year’s Resolution #1: Stick to Worthwhile Tasks and Activities

The new year is upon us, happening too fast, as usual. Just as we get used to the schedule of a Winter Break, we are trying to get a mountain of tasks done before school starts up in a few short days. Where does the time go?

The new year is upon us, happening too fast, as usual. Just as we get used to the schedule of a Winter Break, we are trying to get a mountain of tasks done before school starts up in a few short days. Where does the time go?

That’s really the gist of it, isn’t it? Where does time go? As teachers, we are always scrambling to fit all the learning we can between two bells. We have to cram all the planning, copying, and bathroom breaks into those all too few precious moments, and most of us take the work home, too. We are always squeezing too much into too little time. The struggle is to make all of our time, our students and our own personal time, worthwhile.

I resolve to ensure that my students do not suffer through meaningless busy work.

And, because I am important, too, I will give myself meaningful and worthwhile tasks, too. I will let go of the “busy work” that wastes time, and I will focus on what makes my life more complete. I want to always be able to say, “it’s worth my time.”

New Year’s Resolution #2: Take Time to Celebrate

As I pack away my Christmas décor, removing the sparkle and glow from our home, carefully tucking away old ornaments and our faux Canadian pine, I am feeling sentimental. It all goes by so fast. Not just the holiday, but the year…everything.

In the gloom of winter, we create an artificial shine to remind us of the celebration of all that we love. It’s nice, but it’s fleeting. In light of this, I resolve to make sure that those who are precious to me know that they are. I want to openly value my family and friends, and my students, too.

I resolve to tell my students what is wonderful about each and every one of them.

Likewise, I want to joyfully express my love of learning, of literature, of history and of theater. I want to share what is precious to me with those who I value and hold dear. We should never lose the sparkle and glow that we so intentionally celebrate this time of year. We need to spread it out thouogh the year with enthusiasm.

New Year’s Resolution #3: Expect Great Things in the Future

As I write this, my home is filled with the savory aroma of black-eyed peas, collard greens, and pork. It’s a tradition in our family, and in many places around the country, to eat black-eyed peas on New Year’s. It’s for luck and prosperity in the new year. Wikipedia confirms it: “The peas, since they swell when cooked, symbolize prosperity; the greens symbolize money; the pork, because pigs root forward when foraging, represents positive motion.” It’s a lovely smell, and it brings back a lot of memories. But this year, I am really looking forward to so much more. I have a lot I want to accomplish, so bring on those black-eyed peas!

As I write this, my home is filled with the savory aroma of black-eyed peas, collard greens, and pork. It’s a tradition in our family, and in many places around the country, to eat black-eyed peas on New Year’s. It’s for luck and prosperity in the new year. Wikipedia confirms it: “The peas, since they swell when cooked, symbolize prosperity; the greens symbolize money; the pork, because pigs root forward when foraging, represents positive motion.” It’s a lovely smell, and it brings back a lot of memories. But this year, I am really looking forward to so much more. I have a lot I want to accomplish, so bring on those black-eyed peas!

This year, I will be going on an international field experience with Fulbright’s Teachers for Global Classrooms. Last week I found out that my assignment is in Morocco during March. That is big news and such a trip can only be life changing. I am overwhelmed and excited, to be sure.

However, this year could be amazing for so many other reasons, and I don’t want to lose sight of any of it. I have a grandson to enjoy, a young horse to ride, an amazing family. And, not to be forgotten, I have some incredible students in my life right now. I want to plan for the best possible outcomes for us all.

Luck would be nice, but I am setting my expectations very high.

I resolve to expect great things, from myself and my students.

So, let’s break it down. Here is Mrs. Olmos’s advice for a great 2019, for herself, mainly. However, I think these goals/resolutions could work for any teacher.

- Stick to what is most worthwhile.

- Celebrate all the good stuff.

- Have outrageous expectations.

And have a Happy New Year!

Don’t get me wrong; we need all of the supports mentioned in the proposal. We need more counselors in our buildings. We need plans for school safety that are actionable. We need all educational personnel to be trained to recognize and respond to symptoms of emotional distress. But, does anyone take time to wonder how we could prevent getting to the point where we are responding to distress?

Don’t get me wrong; we need all of the supports mentioned in the proposal. We need more counselors in our buildings. We need plans for school safety that are actionable. We need all educational personnel to be trained to recognize and respond to symptoms of emotional distress. But, does anyone take time to wonder how we could prevent getting to the point where we are responding to distress?

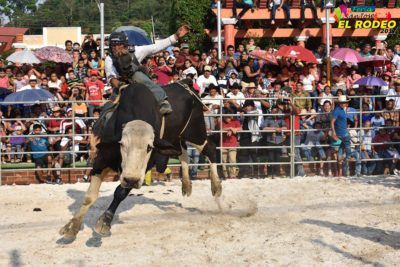

My New Year’s resolution is to not find myself on a bull ride with a student. In bull riding, an eight second ride earns the intrepid rider a spot on the scoreboard. It is intense and tough to do. In teaching, eight seconds can earn your student a chance at learning and you a chance at teaching.

My New Year’s resolution is to not find myself on a bull ride with a student. In bull riding, an eight second ride earns the intrepid rider a spot on the scoreboard. It is intense and tough to do. In teaching, eight seconds can earn your student a chance at learning and you a chance at teaching. Oprah Winfrey often talks about the one thing every person truly wants; to be seen and to be heard. This makes sense and can impact your classroom when kept in mind while teaching. It turns out it can impact whole groups of people when applied to policy making.

Oprah Winfrey often talks about the one thing every person truly wants; to be seen and to be heard. This makes sense and can impact your classroom when kept in mind while teaching. It turns out it can impact whole groups of people when applied to policy making.

Civil discourse is the engagement in conversation to enhance understanding. It requires respect for all others involved, without judgment. You cannot conduct civil discourse if it is obvious that you question the good sense of your peers. You cannot conduct yourself with hostility, sarcasm, mockery, or excess persuasive language. You have to accept the views of others as valid, despite your disagreement.

Civil discourse is the engagement in conversation to enhance understanding. It requires respect for all others involved, without judgment. You cannot conduct civil discourse if it is obvious that you question the good sense of your peers. You cannot conduct yourself with hostility, sarcasm, mockery, or excess persuasive language. You have to accept the views of others as valid, despite your disagreement. As teachers, the urge to stay out of it, to be apolitical and neutral is strong. We don’t want to offend our students, their families, or our communities. However, we must model that we all have views and ideas, and how we express them is important. We do not force our views on others, but, instead, we invite discourse. Our students need to learn to share their ideas and listen to their peers. They need to understand the importance of researching the issues and verifying their sources. They need to practice protocols of debate and dialogue that guide them to be supportive listeners, even when they disagree.

As teachers, the urge to stay out of it, to be apolitical and neutral is strong. We don’t want to offend our students, their families, or our communities. However, we must model that we all have views and ideas, and how we express them is important. We do not force our views on others, but, instead, we invite discourse. Our students need to learn to share their ideas and listen to their peers. They need to understand the importance of researching the issues and verifying their sources. They need to practice protocols of debate and dialogue that guide them to be supportive listeners, even when they disagree. Neil Postman, and, being the serious minded young person I was, I thought hard about both the messages I received and the medium through which I received them.

Neil Postman, and, being the serious minded young person I was, I thought hard about both the messages I received and the medium through which I received them. But, last year I became painfully aware of that my “usual” operations were not working for this particular grouping of students. I could tell their needs were not being fully met and frankly, I was getting burned out trying to span the range of abilities. I needed a change in my thinking surrounding teaching and learning. I began to explore other approaches to teaching and took what I found to my students. I knew that this level of massive change would be akin to fixing a plane while flying it. I needed everyone on board, to be…on board!

But, last year I became painfully aware of that my “usual” operations were not working for this particular grouping of students. I could tell their needs were not being fully met and frankly, I was getting burned out trying to span the range of abilities. I needed a change in my thinking surrounding teaching and learning. I began to explore other approaches to teaching and took what I found to my students. I knew that this level of massive change would be akin to fixing a plane while flying it. I needed everyone on board, to be…on board! In fact, this backwards system of integration may explain why reading scores have flatlined since 1998!

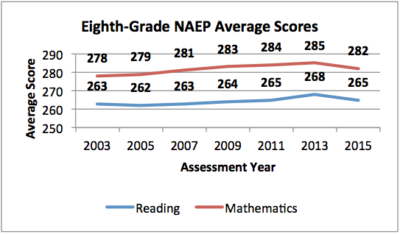

In fact, this backwards system of integration may explain why reading scores have flatlined since 1998!