Eight teachers and three district instructional coaches cram into the meeting room of a local coffee shop, the table full of laptops, large sticky notes, smelly markers, lattes and cell phones. They pore over documents: teacher plans, student work, excerpts from educational articles. The facilitator draws out ideas, pushes back when needed, and propels the conversation forward for more than two hours. The coffee shop owner, familiar with many of these teachers’ faces, asks, “Are you guys working today?” Yep. Six of these teachers already met the previous week after school in order to create the plans that this group is now tweaking. So far: 2370 minutes of brain work in order to plan one 50-minute lesson. Worth it? Definitely.

This past month, my co-teacher, an Exceptional Needs Specialist, and I were the “enactment teachers” for our English department’s “Studio” cycle: teachers within each department take turns hosting other teachers from the department and district instructional coaches for a process that takes several days. The enactment teacher begins by meeting with a coach to dissect his or her “problem of practice” or “problem of student learning,” a challenge that is almost always evident in the other teachers’ classrooms. Later the whole team meets to plan a lesson that will address the stated problem, and finally, over an entire school day, the team finalizes the plan, digs deeper into learning about the problem of practice, observes the enactment teacher teach the lesson to one class, debriefs, watches as the lesson is taught once more, and then, after a long day, shares out in a final debrief.

For this round of Studio, my co-teacher and I identified a problem of practice concerning students working in their “zone of proximal development,” a term defined by psychologist Lev Vygotsky, where students are appropriately challenged and supported at their current level of understanding. We had found that more struggling students often did not take advantage of the supports that we offered, including modified instruction in small-group settings, graphic organizers, one-on-one support, etc.; for students who needed more challenge, we realized that we didn’t always create opportunities for them to go further and deeper, and when we did, sometimes these students either did not realize they were ready for that level of instruction or they didn’t take advantage of the opportunities presented to them.

Through the Studio planning cycle, our group of educators planned a lesson where students identified their current level of understanding of our learning target for the day, and then based on that self-assessment, chose from a menu of options of how they wanted to learn that day, including one that was more supported and one that was more independent. The group also encouraged us to choose a more complex text than the one we had originally planned, arguing that with students being more aware of their current skill level and choosing an appropriate level of support, they could be successful at understanding this level of reading.

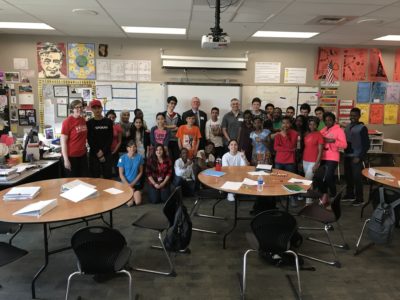

My co-teacher and I stand in front of our classroom with 28 pairs of student eyes on us and 11 pairs of adult eyes on them. The students start off stone cold – no one cracks a smile at my corny jokes. But they slowly warm up, forgetting about the adults there with their clipboards, marking down their every comment and our every movement. They tentatively raise their hands as they catch on to the lesson that these 11 people had a part in planning for them. I smile, impressed with how my students are taking on this complex text, really understanding the heart of the argument. The adults keep their poker faces on, but they are silently cheering students on as they make sense of the reading before them, and quietly jotting down notes for later as they see us make teacher moves that both help and hinder the lesson.

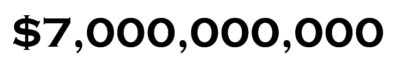

Studio feels a bit luxurious to me. All of these brains helping us with one lesson. All of this energy – and money! – spent to help our department gain a deeper understanding of a problem of student learning that affects us all. All of the details in the lesson plan, the stuff that I rarely have time to think about, let alone write into a formal template. All of the debriefing, refining, and reteaching.

And yet the luxury is worth it. Definitely. That day, 84 students went home after reading a text that I had thought would be too much for them. Those 11 teachers went home with new ideas of what to do – and not do – in their own practice to increase student understanding. And this one teacher, me, left feeling both challenged and affirmed, with new habits of mind and refined practice to take to the next lesson.

endent of Public Instruction, Chris Reykdal outlined a series of phases that addressed his

endent of Public Instruction, Chris Reykdal outlined a series of phases that addressed his