Frank and Lillian Gilbreth were early efficiency experts who did motion study work. The book about their family, Cheaper by the Dozen, explains the technique they used. “A lazy man … always makes the best use of his [time] because he is too indolent to waste motions. Whenever Dad started to do a new motion study project at a factory, he’d always begin by announcing he wanted to photograph the motions of the laziest man on the job” (Gilbreth and Carey, 94).

There are lots of tips and tricks for having effective parent-teacher conferences, from the NEA and KidsHealth to a collection of materials from Edutopia.

But how to be efficient? How to make the best use of your time?

Let me share some ideas. See if there are ones you can adapt to use with your students and your parents.

I have students write in a journal nearly every day. At the beginning of the school year I ask them to write short pieces about gifts or talents they have, ones they wish they had, and ones they are willing to work hard on this year to develop as skills. Often those responses have little or nothing to do with school. They have to do with sports teams or drama classes or art classes. Which is great — I learn a lot about my students’ interests. I have them type those pieces and print them. I hang them on the bulletin board in the hall.

I have students write in a journal nearly every day. At the beginning of the school year I ask them to write short pieces about gifts or talents they have, ones they wish they had, and ones they are willing to work hard on this year to develop as skills. Often those responses have little or nothing to do with school. They have to do with sports teams or drama classes or art classes. Which is great — I learn a lot about my students’ interests. I have them type those pieces and print them. I hang them on the bulletin board in the hall.

(I also use the discussions we have to drive home the point that there are multiple kinds of gifts and talents, not just the ones that get kids placed into self-contained classrooms. And we talk about how everyone has to work hard to improve skills.)

About four weeks into the school year I narrow the focus. I ask students to write in their journals about what they do well at school. I ask them to think specifically about academics and behavior inside my classroom. The next day I ask them to write about what they need to improve. We’ve had a month of school. By now they should be able to pinpoint some areas of success and areas for growth.

The third day I ask them to write about how the adults in their life can help them—parents, grandparents, teachers, whatever grownups they rely on for help.

Once again, I have them type up what they’ve written, but this time I don’t have them print the pieces. They save them into the Kragen classroom folder into a subfolder called “journals.”

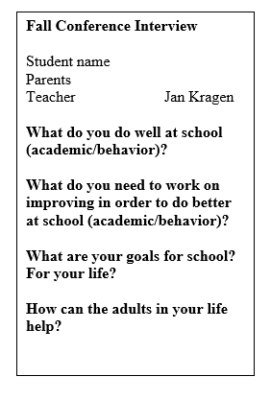

Meanwhile, I have a template for my conferences:

In the week before the conferences, I copy the template, one for each student. I add the student and parent names. Finally, I import the paragraphs each student wrote into their page.

As parents and students arrive for conferences I greet them. I ask the students to collect their most recent papers to go home. I give the parents the STAR test results and any other paperwork from the office.

Just that quickly we are ready to start the interview.

I sit at the computer, facing my student. Parents listen while I conduct an interview. (It’s really hard for them to be quiet and listen, but I ask them to wait to talk until their child is finished.)

First, I ask, “What are you good at? I see you wrote that you are good at math. Are you good at other things too?” As we talk, I add to what the student initially wrote. Sometimes I say, “May I add something? May I put down that you are extremely well-behaved?” or “You do really well in group work.” I’ve never had a student turn me down! It gives me the chance to reinforce the idea that behavior and teamwork are valued skills in the classroom.

Second, I ask for what they need to improve. Usually they have a really good handle on what they need to work on. My contributions are less likely to be additions and more likely to be suggested solutions.

Third, I throw them a curve ball. I ask, “What are your goals for school, for your life? What do you want to be when you grow up? What do you want to accomplish?”

Some children have vague ideas. “I want to get good grades.” I sometimes suggest, “I want to be well-educated?” They usually smile and say yes.

Others have definite plans. “I want to be a veterinarian.” “An entertainer.” “I want to work with robots.” “I want to be an author.” “I want to be an inventor.”

Those responses can lead to a brief but rich conversation.

1.

During the conference I Google the top ten colleges in the field and recommend to the student and parents that they contact the schools to find out what their requirements are. What would the child need to do in high school in order to be a good candidate for the program? Plan ahead!

(My dad did hiring for Lockheed. He told me once that they looked at candidates from only five schools in the US. I always thought that if it was your life-long dream to work at Lockheed it would really be awful to find that out after you graduated from school number six!)

BTW, also look into financial aid at each school. How will you start planning to pay for the college now?

As families take summer vacations, I recommend they visit any of the top schools they might pass. See if they can get a tour.

2.

Find mentors or interview subjects. Can you tour the robotics department at UW? Can you job shadow a scientist?

I won’t take the whole class on a field trip to visit such specific places, but I recommend parents take their own children on personal field trips.

Last summer a girl did field work with a biologist.

“The last question you ask is, who should I talk to next? Daisy chain connections. You may end up finding an area of interest that you don’t even know exists because it’s not something we talk about in a fourth or fifth grade classroom.”

3.

“What’s stopping you? If you want to be an author and write about your travels, start now. You’ve traveled across the country several times. How do you pack for long trips? How do you amuse yourself on long drives?”

“If you want to be an entertainer, start now. Read poems aloud—with GREAT enthusiasm—to the kindergarten classes.”

“Do you know about inventors who are young people?” I suggest the TED talks with Richard Turere and Boyan Slat. “And you should also watch Slingshot on Netflix because you will love it.”

Fourth, I ask each child how the adults can help. By now we may have answered that question within the other sections, but I always like to double-check that I haven’t missed anything.

About this point I turn to the parents and ask, “Is there anything you would like to add? Do you have any questions?”

Virtually every time, the answer is no. Parents tell me the conference feels very thorough.

What you need to notice is that the student has done about 85% of the work. I’ve done some copy and pasting, I’ve added comments into the document, but mostly I’ve had a great time talking to each of my students.

I print a copy of the page for the parents that they can take home immediately. They LOVE not having to take notes!

Of course, I have an electronic copy of everything. In the spring we can pull up the fall conferences and review how well the students are doing.

(In my next post I will share more ways I save time doing conferences!)

But, last year I became painfully aware of that my “usual” operations were not working for this particular grouping of students. I could tell their needs were not being fully met and frankly, I was getting burned out trying to span the range of abilities. I needed a change in my thinking surrounding teaching and learning. I began to explore other approaches to teaching and took what I found to my students. I knew that this level of massive change would be akin to fixing a plane while flying it. I needed everyone on board, to be…on board!

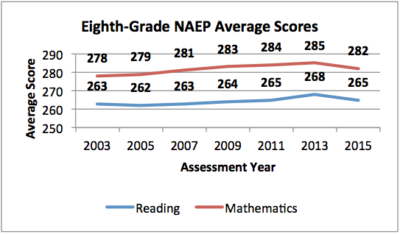

But, last year I became painfully aware of that my “usual” operations were not working for this particular grouping of students. I could tell their needs were not being fully met and frankly, I was getting burned out trying to span the range of abilities. I needed a change in my thinking surrounding teaching and learning. I began to explore other approaches to teaching and took what I found to my students. I knew that this level of massive change would be akin to fixing a plane while flying it. I needed everyone on board, to be…on board! In fact, this backwards system of integration may explain why reading scores have flatlined since 1998!

In fact, this backwards system of integration may explain why reading scores have flatlined since 1998!

“Mommy made me mash my M&M’s,” trills from the nervous troupe of twenty-five on the stage. Kindergarten to high school, these children are all warming up their voices for this summer’s presentation of “Alice in Wonderland” to be presented at our community theater. It is an all-children production; children will be acting, building sets, running lights and generally spending their summer months of June and July busily learning the art of theater. Wow! It is a whirlwind of creativity and intense focus!

“Mommy made me mash my M&M’s,” trills from the nervous troupe of twenty-five on the stage. Kindergarten to high school, these children are all warming up their voices for this summer’s presentation of “Alice in Wonderland” to be presented at our community theater. It is an all-children production; children will be acting, building sets, running lights and generally spending their summer months of June and July busily learning the art of theater. Wow! It is a whirlwind of creativity and intense focus! Universal screening eliminates the reliance on nominations/referrals (which eliminates any potential of bias or problems of access skewing the identification process).

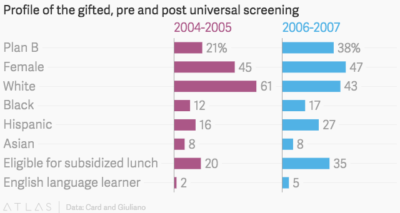

Universal screening eliminates the reliance on nominations/referrals (which eliminates any potential of bias or problems of access skewing the identification process).

After our new Education Secretary, Betsy DeVos, stepped into a public school last week, perhaps for the first time, she told a journalist that the teachers seemed to be “waiting to be told what they have to do.”

After our new Education Secretary, Betsy DeVos, stepped into a public school last week, perhaps for the first time, she told a journalist that the teachers seemed to be “waiting to be told what they have to do.” I’m getting a new student tomorrow. I haven’t met him yet, but I’ve met his discipline record, and it’s staggering. He’s packed more misbehavior into his short life than most of us commit in a lifetime. Not only that, but academically he’s at least three years below the rest of my class.

I’m getting a new student tomorrow. I haven’t met him yet, but I’ve met his discipline record, and it’s staggering. He’s packed more misbehavior into his short life than most of us commit in a lifetime. Not only that, but academically he’s at least three years below the rest of my class. It always starts with a dream. A real dream; not an aspiration or goal, but the kind you have when you sleep. One year it was a poorly-executed field trip to Manhattan (with fourth graders) and another year I had a class of forty but no classroom. I was expected to teach them out on the lawn.

It always starts with a dream. A real dream; not an aspiration or goal, but the kind you have when you sleep. One year it was a poorly-executed field trip to Manhattan (with fourth graders) and another year I had a class of forty but no classroom. I was expected to teach them out on the lawn.