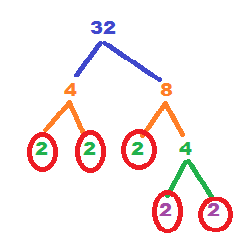

Wednesday was the last day of my thirty-second year teaching. Besides a flurry of part-time teenage jobs, I’ve never really done anything else and I honestly can’t imagine a different career.

Wednesday was the last day of my thirty-second year teaching. Besides a flurry of part-time teenage jobs, I’ve never really done anything else and I honestly can’t imagine a different career.

Despite my apparent longevity (or stagnation) I am not the same teacher I was back in 1984. I’ve learned a few things, sometimes the easy way, but mostly the hard way. Here, in no particular order are some of them:

- Get good at classroom management. It’s not the most important thing we do, but none of the important things can happen without it.

- Relationships matter. Especially your relationships with the principal, the office manager and the custodian.

- Don’t pull maps down past the line that says “Don’t pull past this line.”

- Don’t lose your school key. It’s a huge mess.

- Take your job seriously. It’s about the most important job you can imagine.

- Don’t take yourself too seriously. You aren’t as special as your mother said you were.

- Stay in shape. That’s good advice in general, but this job definitely has a physical component. I’ve seen teachers let themselves go only to have their careers cut short.

- You can’t change people. I’m not talking about students; changing students is actually our job. I’m talking about other people, like colleagues and parents. It might be nice to change some of these people, but you can’t.

- This is not a competitive job. Trying to be the best teacher is a waste of time and energy.

- The reason we have assessments is to improve instruction. It’s not the other way around.

- Don’t go to work when you’re sick. Don’t call in sick when you’re not.

- The kids who need the most love are the hardest kids to love. And you should sit them towards the front.

- Go to most of the staff parties, but don’t bring your spouse; they won’t enjoy it. And don’t get drunk.

- Don’t expect anything productive to happen when you have a sub.

- Work hard, but sustainably hard. You’re not being paid to work 70-hour weeks, and doing so will have a negative effect on the 35 hours for which you are being paid. Know when to quit.

- Grade papers immediately. Student work does not become more interesting over time.

And finally,

17. Support your union. Those are good people.

It’s been a great thirty-years. That doesn’t mean every minute of every day was bliss, but it does mean that I can look back knowing I’ve done something important with myself. And that’s saying something.

And I’m not even close to being done. In fact, I’m shooting for fifty. So that’s thirty-two down and eighteen to go!

By Tom White

By Tom White By Tom White

By Tom White Senator Pam Roach introduced

Senator Pam Roach introduced