We asked our bloggers to tell us about their experience with culturally responsive teaching. We asked them:

What does culturally responsive teaching look like in your district?

How are you and the educators you know using relationships to connect with students, honor their individuality and support academic achievement?

Gretchen Cruden

Culturally responsive teaching may look a little different in our school. I work in a high-poverty, extremely rural school. Example? We are so rural that we are defined as a frontier school and have had “cougar patrol” as part of our playground supervisory activities. That said, our school embraces what our students walk in the door with and honor it. We are a culture of “make do” and “outside the box” thinking because our students often do have to be creative in their problem solving in their home environments. We embrace learning that connects with their real lives including studying outdoor survival skills, gardening and dissecting parts of animals their families have hunted. These lessons honor their home lives and connect families to the school. In this way, our school embraces and supports our students’ backgrounds and helps build bridges to adjacent possibilities as they grow in their academics.

Lynne Olmos

For all the time I have worked in my small, rural district, there has been a sort of self-congratulatory attitude in our district. We are proud of our students of color and how successful they are in our schools. However, that success is really a tribute to their hard work more than it is to any sort of outreach or responsive programs built into the system. Latinx families make up around 35% of our community, and, though we have a migrant support program that hosts occasional events and the standard English language learner supports, we don’t do a great deal to celebrate Latinx culture. Our kids are awesome, and some of our teachers go the extra mile to embrace the diverse cultures in our classrooms. However, there is a need for a more culturally responsive system.

Every now and then, we get the opportunity to celebrate our diversity. One very cool opportunity that landed in my classroom recently was through a national project funded by the CDC and managed by the Olympia Family Theater. The project, entitled Fully Vaxxed, utilized the input of bilingual youth from our school and a few others to write plays about the impact of the Covid vaccines on Latinx communities. Three of my students participated in the program, and our Drama Club attended opening night to celebrate their work. It was awesome!

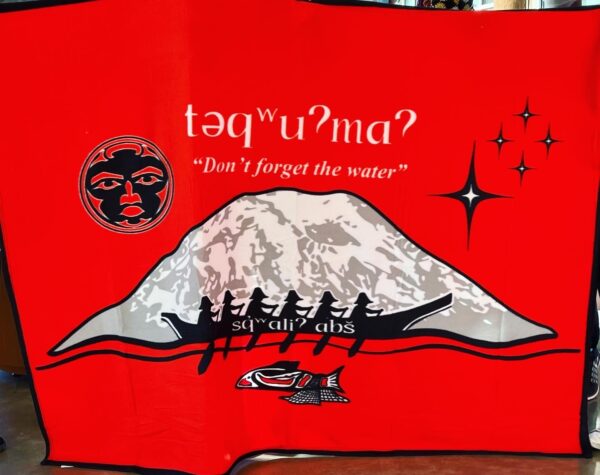

We really do a great job supporting all students in my district, but more celebrations of diverse cultures could benefit us all. Everyone deserves to see their home language, culture, and traditions represented, respected, and honored in their school environment.

Emma-Kate Schaake

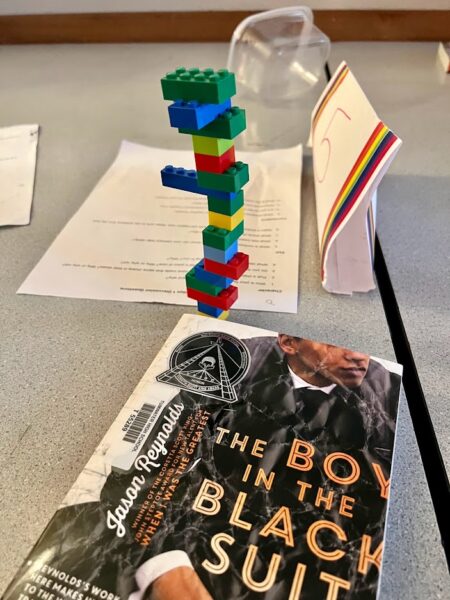

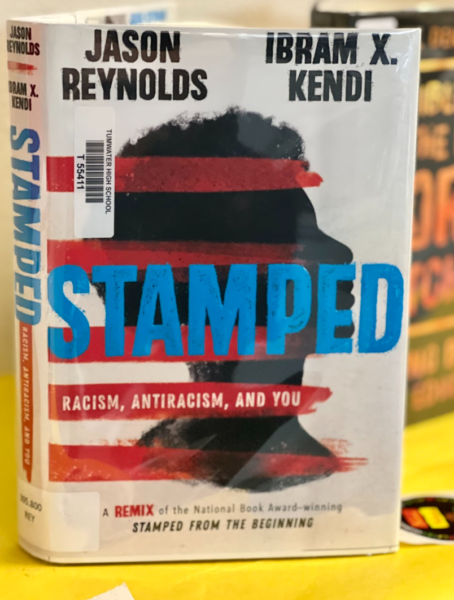

I am grateful to have a district and department with enough funding to have some creativity in lesson planning and curriculum. Last year, I was able to buy four class sets of contemporary young adult books for book groups and that unit was the best engagement I had online by far. The English teacher saying that books should be windows into other perspectives or mirrors into your own is almost trite by now, but still incredibly true.

The books we read allowed students to share their own experiences and empathize with the characters. As much choice as I can offer in my curriculum, the better. I want students to know they have strengths in their cultural, linguistic, and ethnic backgrounds, regardless. So often, students do not see themselves in texts (especially those written by old, dead, white men) and I try to deviate from that norm as much as I can.

So now it is your turn.

Tell us how your school responds to the culture of its students. How do you connect with your students, honor their culture, and support their academic achievement?