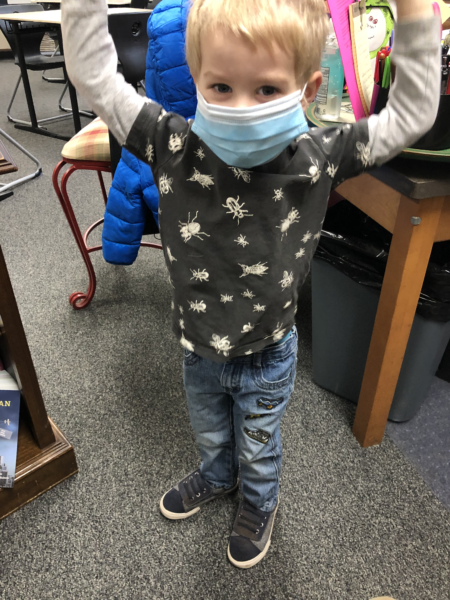

This post was written by Kim Broomer, 2025 Washington State Teacher of the Year. Kim is a kindergarten teacher at Ruby Bridges Elementary in the Northshore School District. Kim is a dynamic educator committed to inclusive schools and creating a culture of belonging for each and every student she works with in her classroom and beyond.

**********************************************************

Every child deserves access to their neighborhood school, learning alongside their siblings, neighbors, and peers. Yet, in many cases, students with disabilities are denied this fundamental right. They are sent to schools outside their communities, under the rationale that their needs are “too complex” for general education teachers to handle. This misconception not only segregates students but also undermines the potential of educators to rise to the challenge of inclusion.

Sarah’s story is a poignant example of why this must change. Sarah was a bright and capable student with complex communication needs who was denied enrollment at her neighborhood school. While her brother and neighborhood friends rode to school together, she was sent to a school miles away. The reason? Her needs were deemed too intricate for her neighborhood school to accommodate. But when Sarah joined my classroom, it quickly became clear that her needs weren’t “too complex” at all, they were simply misunderstood.

Challenging the Myth of “Too Complex”

The notion that only special education teachers can meet the needs of students like Sarah is a myth rooted in outdated beliefs about disability and education. General education teachers are fully capable of teaching students with disabilities. Inclusive education isn’t about having all the answers upfront; it’s about a willingness to learn, adapt, and partner with specialists to meet the needs of every student.

Sarah’s presence in our classroom was a gift. She used an augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) device to express herself, and her interests, humor, and insights quickly became a vibrant part of our community. With support from our special education team, we developed strategies that worked for her—integrating visuals into lessons, building in movement breaks, and using peer modeling. Far from being a burden, Sarah enriched our classroom, teaching us about patience, resilience, and the power of inclusion.

Schools Have a Responsibility to Their Communities

Every school has a responsibility to educate the students within its boundaries, regardless of ability. Denying students like Sarah access to their neighborhood schools sends a harmful message: that inclusion is optional and that some students belong elsewhere. This segregation not only isolates students with disabilities but also deprives their peers of the chance to learn from and with them.

Inclusion benefits everyone. Research shows that students in inclusive classrooms, both with and without disabilities, perform better academically and develop stronger social and emotional skills. Teachers in inclusive settings grow professionally, through learning new strategies that make them better educators for all students.

The Path Forward: Embracing Inclusion

Sarah’s success at school highlights what is possible when schools embrace inclusion. By working together, general and special education teachers, families, and administrators, we created an environment where she could thrive. Her story is a reminder that no student is “too complex” for their neighborhood school.

It’s time to dismantle the systems that segregate students and encourage collaboration that empowers general education teachers to meet diverse needs. Inclusion is not just a possibility, it is a necessity. When every child is welcomed, supported, and celebrated in their local school, we all grow stronger as a community.

Kim Broomer, NBCT

2025 Washington State Teacher of the Year

Kindergarten Teacher

Ruby Bridges Elementary