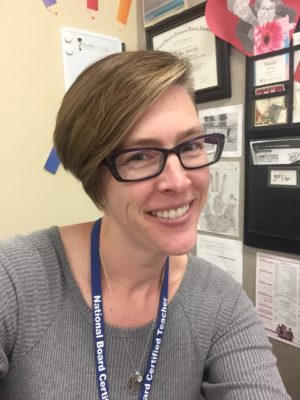

I’d had my heart set on reading To Kill a Mockingbird to my current eighth graders since last spring. Thanks largely to Nancie Atwell’s influence (see The Reading Zone, 2007), I no longer assign whole class novels. Instead, read-alouds allow for an accessible whole class experience that supplements students’ independent reading. I know I am lucky to teach at a school where I am trusted to make such pedagogical and curricular decisions.

Although it had been a long time since I’d read it, I was confident that To Kill a Mockingbird would be a valuable literary experience. It would also offer opportunities to connect to and discuss current issues of racism and the justice system. When I revisited it, however, I noticed several challenges. There’s the matter of the narrator’s southern accent, which I knew I could not pull off. There is also dialect and the N-word. I prepped the kids for it, gave them a lot of contextual information, and decided to use an audio recording. Despite those efforts, the kids were disengaged. Whenever I paused for discussion, my usually opinionated and insightful students remained silent. After a couple of days, they asked me to abandon the audio recording and read it aloud myself. I tried, but they were still disengaged. At that point, Anisa said, “Jessie, we know this is a book you really like, but do you think you could choose a book that we would like?”

I grappled with that question for the rest of the day. Did we just need to give the book more time, or was it truly not the right book?

I remember the year I used David James Duncan’s The River Why with ninth graders. I had loved that book, and I was certain that everyone in a pre-Advanced Placement English class would love it too. After all, what adolescents wouldn’t love a coming-of-age story full of humor, self-discovery, and romance? I could not have been more wrong. The kids hated it. They did not connect with the main character; the humor was too sophisticated. There was a near revolt.

My selection of Angela’s Ashes, on the other hand, was transformative for my juniors and seniors, who could both appreciate the humor and empathize with the depictions of extreme poverty. What had been a disconnected, disengaged group of students developed community and confidence. That was when I learned the power of the right book for the right group at the right time.

Are there some books that are universally the right book? Maybe. It seems that every group of seventh graders loves The Outsiders. But most of the time, I have to start with my group of students in mind, and search for the book that will be the right match. I had forgotten to do that when I selected To Kill a Mockingbird, and then, against my better judgment, I continued to put the curriculum ahead of the students. Anisa’s question gave me the jolt I needed to change course. The next morning, I told the kids that I valued To Kill a Mockingbird and hoped they would each choose to read it at some point, but I could see that it was not the right book for the class at this time.

Wanting to get us back into our read-aloud groove, I pivoted to Wonder by R.J. Palacio. It is engaging, but lacks the literary heft I know my students are ready for and need. During a discussion about what makes a book interesting, Yasmin mentioned Of Mice and Men as an example of a book that had a powerful emotional impact. Isaac and Steven agreed. Yasmin then bounced out of her seat, saying Of Mice and Men should be our next read aloud book. I looked at Isaac and Steven who nodded vigorously. I’d been considering Of Mice and Men. The students’ enthusiastic endorsement settled the matter.

I imagine that there are individuals who would see this course of events as a reason not to trust teachers’ professional judgment, and instead to centralize all decisions about instructional materials at the district or school board level. For me it has the opposite effect. It makes me think about the absurdity of individuals far removed from classrooms making decisions about text selections. If I, who know my students deeply, can occasionally make the wrong choice, how could it be alright to leave the decision making to individuals who don’t know my students at all?

In this age of teacher-proofing and mandated curricula, I am curious about other teachers’ experiences. Are you able to make decisions about what will be the right book for the group in front of you? How do top-down decisions about curricula affect your and your students’ experiences?

Oh, and if you have any middle school read-aloud recommendations, please pass those along too.

I should be reading

I should be reading